News

Can A Cocktail Of Vitamins And Steroids Cure A Major Killer In Hospitals?

By: Richard Harris | NPR

Posted on:

Scientists have launched two large studies to test a medical treatment that, if proven effective, could have an enormous impact on the leading cause of death in American hospitals.

The treatment is aimed at sepsis, a condition in which the body’s inflammatory response rages out of control in reaction to an infection, often leading to organ damage or failure. There’s no proven cure for sepsis, which strikes well over 1 million Americans a year and kills more than 700 a day.

In early 2017, Dr. Paul Marik announced that he had started using a treatment that he says was saving the lives of most of his sepsis patients. The claims were so audacious, Marik says, some doctors called it snake oil.

“There obviously was enormous resistance at the beginning,” he says, “but it seems that with time, people started thinking about it and saying, ‘maybe this isn’t as outrageous as we first thought.’ ”

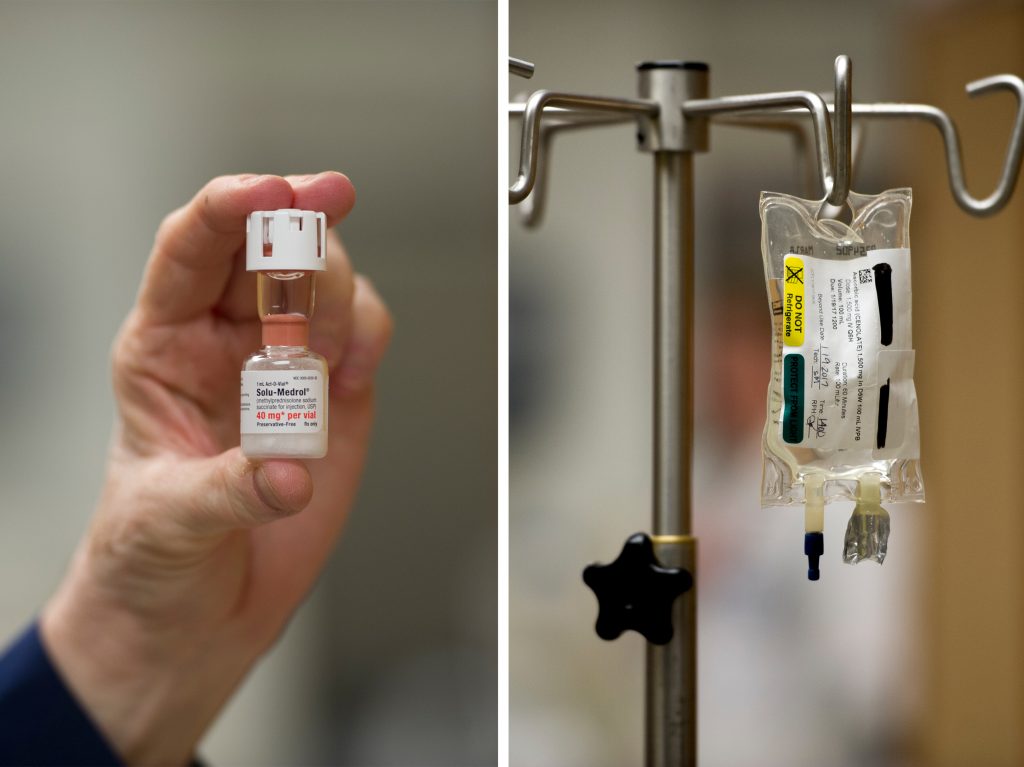

The treatment is a cocktail of intravenous vitamin C, vitamin B1 (thiamine) and corticosteroids. The use of vitamin C in sepsis was pioneered by Dr. Alpha Fowler at Virginia Commonwealth University. Marik has been using the combination treatment since 2016 at his hospital in Norfolk, Va., where he also teaches at the Eastern Virginia Medical School.

Some other doctors around the nation have also been trying it on their patients, but most are waiting for hard science to decide whether Marik’s experience is just a fluke.

That evidence could come from two large studies now underway in the United States. Both are being conducted according to the gold standard of medical science: Some patients get the treatment, others get a placebo, and neither the patients nor doctors know who gets what.

The stakes are enormous, given the number of people who die of sepsis.

“This is something which, if proved to be true, would be a game-changer, almost a miracle cure, honestly,” says Dr. Craig Coopersmith, a critical care surgeon at Emory University and a member of the team running one of the two sepsis studies, the VICTAS Study.

Planning research like this takes significant effort and funding. The effort involved figuring out which patients would be included and orchestrating patient care and data collection from 24 to 40 different hospitals. Competitive grants through the National Institutes of Health often take years to land, so instead this trial reached out to the Marcus Foundation in Atlanta (funded by family members of the Home Depot fortune).

“We’ve all been pretty much working 24/7 on this for the past three to five months,” says Dr. Richard Rothman, a professor of emergency medicine at the Johns Hopkins hospital in Baltimore, who is a leader of the VICTAS study.

Marik has a biologically plausible explanation for how his protocol could work. He says the sepsis reaction generates large amounts of a damaging molecule called reactive oxygen, which vitamin C neutralizes.

When Marik published his protocol in early 2017, Coopersmith was in the wait-and-see camp. But as he became involved in planning the study, he decided to get some hands-on experience with the protocol, working with patients in his hospital.

Some patients he treated with it died. But he also tells the story of a man who was “so sick that we actually had to flip him upside down to get enough oxygen into his body,” Coopersmith says. “His kidneys had failed. His liver wasn’t working, his bone marrow wasn’t working and statistically his chance of dying was nearly 100 percent.”

Coopersmith gave the man the Marik cocktail and his condition quickly reversed. Six days later he was off of the ventilator that had been keeping him breathing, and on the seventh day he was well enough to leave the intensive care unit.

“We would call it a miracle cure,” Coopersmith says. “What we don’t know is [whether] he was going to get better independent of the vitamin C, steroids and thiamine — or did that make him better.”

The answer to that question will be informed by the VICTAS study. The study will soon be enrolling hundreds of patients in Atlanta, Baltimore, Marik’s hospital in Norfolk, and up to three dozen other hospitals. (The exact number of study sites will depend on how quickly the early ones are able to recruit patients.)

At the same time, doctors at the Harvard-affiliated Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center are launching another large study, involving 13 hospitals. They got a $3 million grant from the Open Philanthropy Project to study the Marik protocol.

“Our goal is to complete this trial within a year from now,” says Dr. Michael Donnino, who is leading that study. As of the end of April, he had enrolled 11 patients at his hospital. Hospitals in New York state and Michigan launched the study at their institutions this week.

The parallel studies will help make whatever answer emerges all the more credible, Donnino says. Reproducibility is the keystone of science.

“Having another trial out there I think is great,” he says.

Both research trials have outside experts sitting on boards that will monitor data and safety; they will periodically take a peek at the accumulating data. If the results are as dramatic as Marik gets in his hospital — or on the other hand clearly futile — the studies could be called off early.

“And either way, it will change practice across the United States and across the world,” Coopersmith says. He guesses that around 10-20 percent of intensive-care specialists are currently using the Marik cocktail.

There’s reason for both optimism and for caution. There have been more than 100 studies of proposed treatments for sepsis over the years, and previous results that seemed promising at first flopped after further examination. But the potential upside is beguiling: a lifesaving treatment that’s affordable.

“It’s not going to be the equivalent of a new drug in cancer or hepatitis, which costs $50,000 to $100,000 and you have to make the decision if insurance doesn’t cover it, whether or not to mortgage the house and give away your inheritance,” Coopersmith says. “This is something that’s going to be very, very cheap and accessible throughout the world.”

That is, if it works.

You can contact Richard Harris at rharris@npr.org.

9(MDI4ODU1ODA1MDE0ODA3MTMyMDY2MTJiNQ000))