Communiqué

Murder ignited a firestorm of racial tensions in “The Zoot Suit Riots” on AMERICAN EXPERIENCE, March 29 at 9 pm

< < Back toAmerican Experience Zoot Suit Riots To Have Encore Broadcast

Tuesday, March 29, 2022 on PBS and PBS.org

80 Years Ago, the Murder of a Young Mexican-American Man Ignited a Firestorm of Racial Tensions in World War II-Era Los Angeles

Los Angeles in 1942 was on the verge of exploding. Wartime tensions, an influx of servicemen, overzealous authority, rebellious youth and racial strife brought the city to its breaking point. At the center of the conflict were 50,000 sailors, itching to blow off steam before they shipped off to war, and Mexican American teens called “zoot suiters” for the baggy pants and long jackets they wore. For the sailors and many white Los Angelenos, the zoot suiters had come to symbolize all that was wrong with the city. Vividly capturing the moment when tensions boiled over and the city erupted into some of the worst violence in its history, Zoot Suit Riots features evocative archival footage and interviews with a wide variety of eyewitnesses and historians. Written, directed and produced by Joseph Tovares and narrated by Hector Elizondo, the film, originally broadcast in 2002, will have an encore broadcast on Tuesday, March 29, 2022, 9:00-10:00 p.m. ET on PBS, PBS.org and the PBS Video App.

The mood in wartime Los Angeles was one of tension and suspicion. Less than a century before, Los Angeles had been part of Mexico but by 1942, Mexican Americans were seen as racially inferior and vulnerable to manipulation by enemy agents. At the same time, Mexican American youth were rebelling against the culture of the tight-knit barrios of their parents. They punctuated their speech with jazz phrases like “hip” and “cool” and took fashion cues from African Americans, favoring the zoot suit’s exaggerated baggy pants and long jackets. Shocked by their outrageous clothes and cocky attitudes, their parents feared they were becoming pachucos or punks.

On August 1, 1942, 19-year-old Hank Leyvas and a group of his friends from L.A.’s 38th Street crashed a party near a swimming hole dubbed the “Sleepy Lagoon.” Claiming the partygoers had beaten him and his girlfriend earlier, Leyvas was determined to get revenge. A brawl ensued. After Leyvas and his friends left the party, neighbors found Jose Diaz badly beaten and stabbed. His subsequent death was a call to action for the city’s police, for whom Mexican American youth crime had been a growing concern.

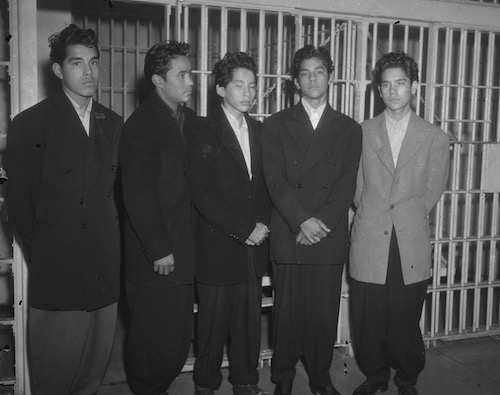

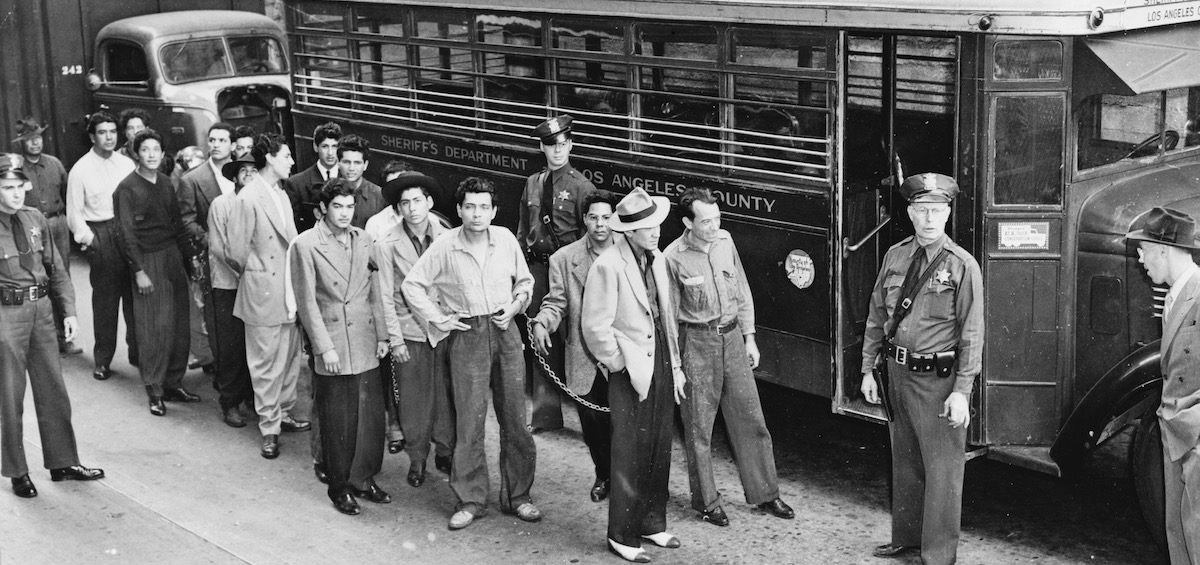

Within 48 hours, a police dragnet snagged 600 young Mexican Americans; Leyvas and 21 others were indicted for Diaz’s murder. When the Sleepy Lagoon trial began in October 1942, it was the largest mass trial in California history. Judge Charles Fricke presided over the case. Overruling objections from the defense, he sat all the defendants together, isolated from their lawyers, and refused to permit them to clean up or change their clothes for the trial.

The 38th Street kids testified that when they arrived at the party, two girls in their group found Diaz lying in the shadows, mortally wounded. They attended to him while Leyvas and his friends fought with others. The defendants admitted that one boy hit Diaz, but they denied responsibility for his death. Neither the press nor the jury believed their story.

On January 12, 1943, 17 defendants were found guilty. Leyvas was sentenced to life in San Quentin prison. Believing the boys had been railroaded, a group of intellectuals and Hollywood celebrities — Orson Welles and Rita Hayworth among them — lent their names to the Sleepy Lagoon Defense Committee.

In the months following the trial, sailors and zoot suiters squared off in regular skirmishes as tensions mounted. On June 3, dozens of enraged sailors armed with belts and clubs set off to avenge an attack on a sailor several nights before. The bloody confrontations between servicemen and zoot suiters that followed marked the beginning of the Zoot Suit Riots.

Over the next five days, sailors focused their attacks on zoot suiters; then they unleashed their rage on any Mexican American in their path. The fighting spread from downtown into the barrios of East L.A. The sailors stripped zoot suiters and burned their clothing in the streets. On the fifth day of the riots, 5,000 civilians showed up to assist the service members. Mexican American kids organized and fought back.

For days, the LAPD hung back. Finally, on June 8, military authorities and civilian leaders declared the city off-limits to servicemen, ending the rioting. The next day, the city council banned the wearing of zoot suits on LA streets.

For days, the LAPD hung back. Finally, on June 8, military authorities and civilian leaders declared the city off-limits to servicemen, ending the rioting. The next day, the city council banned the wearing of zoot suits on LA streets.

Ironically, Hank Leyvas and the 38th Street boys were sheltered from the Zoot Suit Riots in prison. The Sleepy Lagoon Defense Committee successfully appealed their case, claiming that they had been denied a fair trial. The 38th Street boys were released in October 1944 after serving two years in prison. Although the boys were not cleared of the murder charge, the LA authorities decided not to re-try the case. In 1944 a still defiant Hank Leyvas walked out of prison — wearing a zoot suit. But the Sleepy Lagoon episode would mark him and the other boys for life, many returning to prison not long after their release.

Decades later, Lorena Encinas, who had been at Sleepy Lagoon, revealed a long-held secret to her children. Her brother Louie and his friends had attacked Jose Diaz and left him to die before Hank and his group even arrived at the party.

Hank Leyvas died in an East L.A. bar in 1971. Jose Diaz’s murder remains officially unsolved.

American Experience Zoot Suit Riots will stream simultaneously with broadcast and be available on all station-branded PBS platforms, including PBS.org and the PBS Video app, available on iOS, Android, Roku, Apple TV, Amazon Fire TV, Android TV, Samsung Smart TV, Chromecast and VIZIO. All titles will also be available for streaming with closed captioning in English and Spanish. PBS station members can view many series, documentaries and specials via PBS Passport. For more information about PBS Passport, visit the PBS Passport FAQ website.