Communiqué

The second deadliest disaster in California history, “Flood in the Desert” on AMERICAN EXPERIENCE – May 3 at 9 pm

< < Back toAmerican Experience Flood in the Desert

Premieres Tuesday, May 3, 2022 on PBS

New Documentary Explores the Deadly St. Francis Dam Disaster, A Story of Hubris, Power, and the Unending Quest to Bring Water to Southern California

Just before midnight on March 12, 1928, about 40 miles north of Los Angeles, one of the biggest dams in the country blew apart, releasing a wall of water 20 stories high. Ten thousand people lived downstream. The St. Francis Dam disaster not only destroyed hundreds of lives and millions of dollars’ worth of property; it also washed away the reputation of William Mulholland, the father of modern Los Angeles, and jeopardized larger plans to transform the West. A self-taught engineer, the 72-year-old Mulholland had launched the city’s remarkable growth by building both an aqueduct to pipe water 233 miles from the Sierra Nevada Mountains, and the St. Francis Dam, to hold a full year’s supply of water for Los Angeles. Now Mulholland was promoting an immense new project: the Hoover Dam. The collapse of the St. Francis Dam was a colossal engineering and human disaster that might have slowed the national project to tame the West. But within days a concerted effort was underway to erase it from popular memory. Directed by Rob Rapley, executive produced by Cameo George, and featuring interviews with historians, engineers and descendants of survivors of the tragedy, Flood in the Desert premieres Tuesday, May 3, 2022, 9:00-10:00 p.m. on American Experience on PBS, PBS.org and the PBS Video App.

Although the dam burst in 1928, the events that led to the disaster began on a November morning in 1913, when 40,000 Angelenos gathered to celebrate the opening of the Los Angeles Aqueduct. One of the wonders of the modern world, it would bring enough water for two and a half million people, from the Sierra Nevada Mountains to the outskirts of Los Angeles. It also supplied almost all the electricity for the city. With clean power and abundant water, the city’s residents were poised to build a bright new life. The mastermind behind the aqueduct, William Mulholland, an Irish immigrant who had worked his way up from digging ditches for the city, became one of the most respected and powerful men in Los Angeles.

But the settlers at the source of L.A.’s water in the Owens River Valley were deeply angry about how the city had secretly bought up their land and water rights. As Los Angeles prospered, their water was almost completely gone, and their farms and towns withered.

In the early 1920s, Southern California was suffering through years of drought, and the aqueduct flow had been cut in half. If Los Angeles was to avoid shortages, Mulholland saw no option but to take even more water from the Owens Valley. The anger there grew ever deeper and provoked citizens to act. They dynamited sections of the aqueduct, opened up valves to release water and demanded reparations. A long and violent conflict ensued, which became known as “California’s Little Civil War.”

Although valley residents saw themselves as victims and were portrayed as such in the press, the white settlers of Owens Valley had themselves displaced the Northern Paiute people in the 1850s and 60s. The Paiutes had lived there for a thousand years, sustained by elaborate irrigation systems that they built over centuries. The settlement of the Valley had been brutal, but in the conflict between the Owens Valley settlers and Los Angeles, the fate of the Paiutes was largely forgotten.

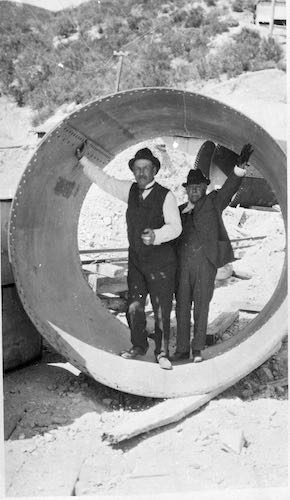

As the massive St. Francis Dam was being built, Mulholland was distracted by plans for an even bigger project — Hoover Dam. As a result, the St. Francis Dam was designed with almost no oversight. Mulholland actually modified the design on the fly, adding 20 feet to its height without widening the base, a change that would have catastrophic consequences.

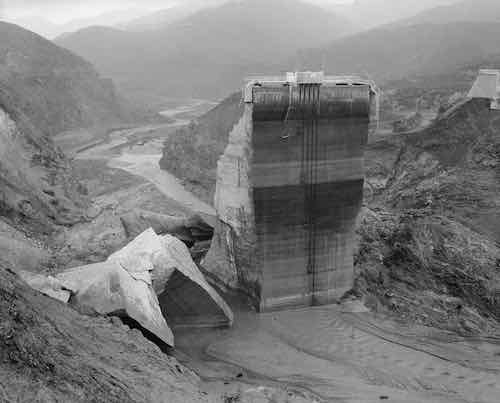

On March 12, 1928, five days after the reservoir was filled to capacity for the first time, the dam — a wall of concrete 20 stories high, holding back 12 billion gallons of water — collapsed. A roaring 120-foot wave of water crashed down the canyon, demolishing everything in its path.

The dam was so profoundly flawed that it took engineers decades to tell which of its many shortcomings was responsible for the collapse.

The flood killed almost everyone in the small community at an electrical generating station along the aqueduct. At the base of the canyon, the floodwaters roared through the Santa Clara River valley. One town after another was destroyed, and almost 400 people were killed. Because the area was home to large numbers of migrant workers and their families, the exact toll will never be known.

The worst civil engineering disaster in American history, it occurred on the eve of a crucial Senate vote to fund the Hoover Dam. Overnight, the whole enterprise was thrown into jeopardy. At a coroner’s inquest, Mulholland accepted responsibility for the St. Francis calamity; he retired in the fall of 1928. A few weeks later, the Senate finally approved Hoover Dam. Mulholland died on July 22, 1935, two months before the dedication of Hoover Dam.

Almost a century later, Los Angeles still wrestles with the challenges of sustaining an ever-growing metropolis in an inhospitably arid climate. “We’re going to have to learn to manage our resources — most particularly water,” says author Jon Wilkman. “Where are we going to get it from? What are we going to do with it? This story, as little known as it is, is a warning.”

Says director Rob Rapley: “The modern West was in many ways conceived in the first decades of the 20th century. It is the result of a national project to divert the waterways, reshape the environment, and build great cities. Today that West is facing a crisis of fire and thirst. As we seek a path forward, it is useful to remember how we got here.” Adds Cameo George, American Experience Executive Producer: “the story of the St. Francis Dam collapse is a tragic reminder of the price we pay when we continually attempt to bend nature to our will. This film – sadly – couldn’t be more timely.”