News

After Obamacare: Disability Services At Risk In Medicaid Changes

By: Mary Meehan | Ohio Valley ReSource

Posted on:

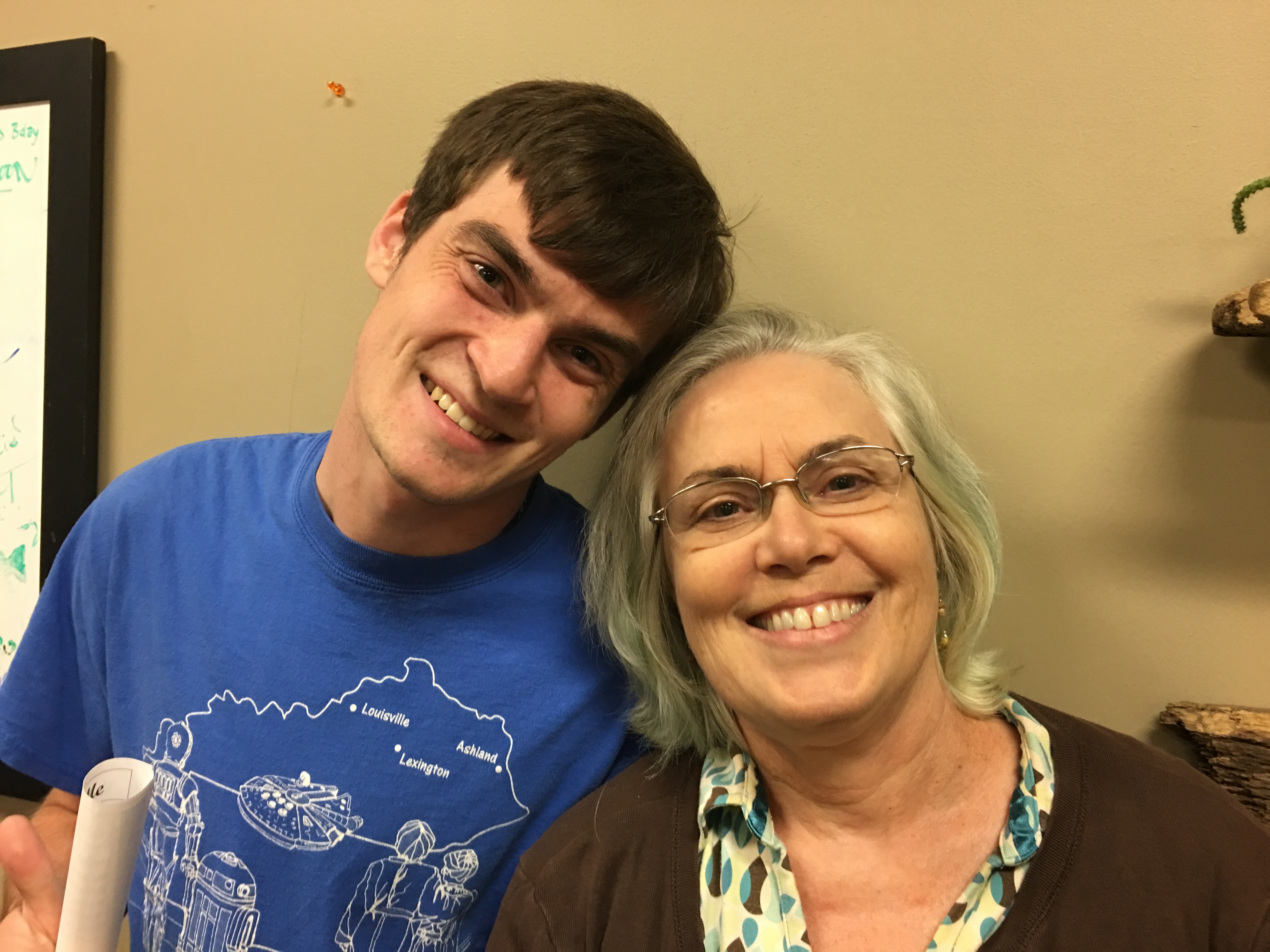

The young man with dimples and an easy smile stood in front of an audience seated in folding metal chairs. Jake Parsons talked a little about his life, and how, as someone living with a disability, he’s able to do what he does.

“I’m 24 years old. I am a member of the Kentucky Star Wars Collectors Club, I have two jobs and I am a registered voter and I vote in almost every election,” he said.

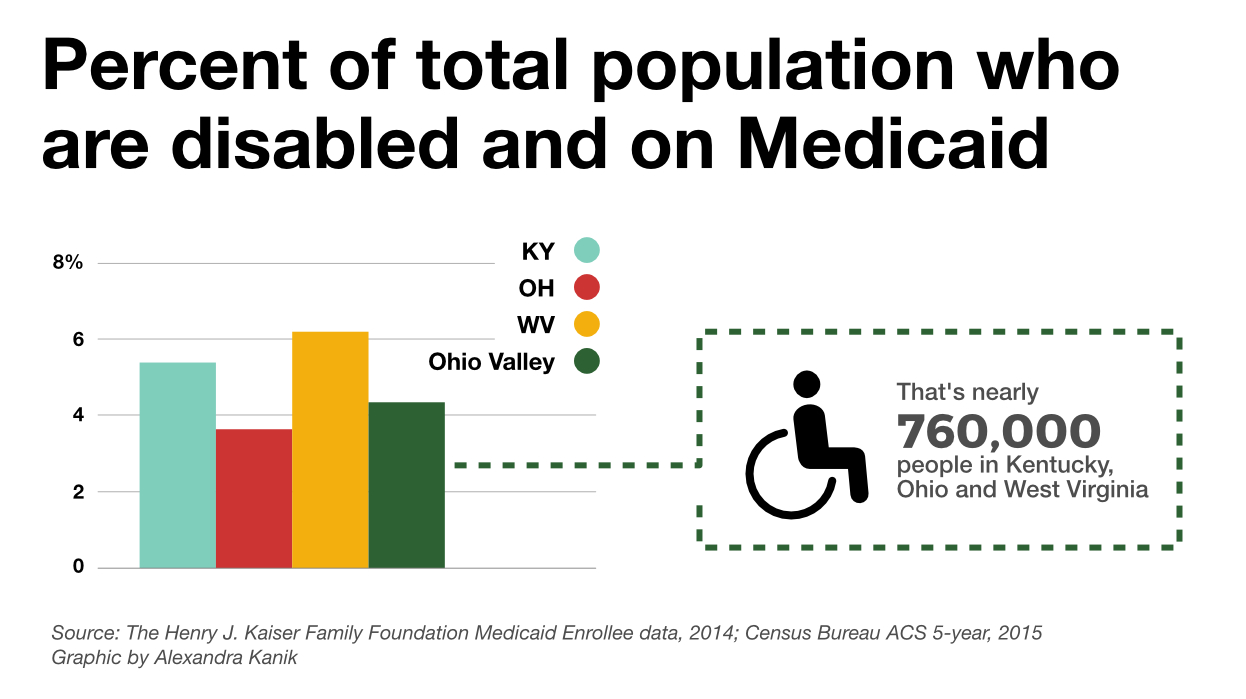

For decades Medicaid has made it possible for people like Parsons to live outside of institutions and in communities. According to the Kaiser Family Foundation nearly 760,000 people with disabilities in Kentucky, Ohio, and West Virginia depend on Medicaid. Parsons depends on help in his day-to-day life.

“Workers help me do things like swimming, doing sports, walking the dog and shopping. If I didn’t have a job coach and workers, I would have to stay home a lot without having a job, which would be kind of boring,” he said.

The audience of caregivers and advocates for the disabled applauded. Stories like this, they hope, will help to show what’s at stake with possible health care changes.

Third-Class Citizens?

The recent meeting at ARC of Central Kentucky in Lexington focused on proposed cuts to Medicaid pending in Congress and the impact the legislation might have on people with disabilities. The tense discussion was peppered with terms such as “dire’ and “catastrophic.”

Jeff Edwards is Executive Director of Kentucky Prevention and Advocacy. He said there is a persistent myth about the scope of abuse of the Medicaid system.

“It’s automatically assumed that there are all of these people who are just using tax dollars and that’s not the case,” he said. A lot of people with disabilities are able to contribute to their communities with a little assistance.

“When we hear they are going to dismantle Medicaid we are thinking about adults, people who need some help in the morning to get dressed and get in a wheelchair but then go onto work a 40-hour-a-week job,” he said.

Edwards said the support services offered through Medicaid allow caregivers to continue to work and pay taxes.

That would change, he said, if those services are cut.

“We will start filling institutions back up,” he said.

If the proposed cuts go through, he said, people with disabilities “become third and fourth class citizens and they don’t have the choices that everyone else does, they don’t have the expectation that everyone else does of living and being a part of a community.”

“Hands off Medicaid”

Nyketa Williams is disabled and said she depends on Medicaid for her transportation, her job and her apartment. She also serves on the board of several of non-profits helping people with disabilities.

She is most concerned about potentially losing her apartment, which she shares with a roommate. She said she doesn’t where she would live.

Williams said she’d like to tell legislators this: “Keep your hands off Medicaid.”

Wendy Wheeler Mullins is one of those caregivers who is able to work part-time because her daughter, Amelia, has a caregiver funded through Medicaid. Amelia is autistic and speaks only a few words. She communicates primarily through a tablet device paid for by Medicaid.

Mullins said she also worries what will happen to Amelia later in her life, a fear made worse by the threat of cuts. “You want to protect your children,” she said, “but I am not going to be here forever.”

No Plan B

So what, exactly has changed? The bill being considered in the Senate would fundamentally change how Medicaid is paid for. States will instead operate under a funding cap and could cut “optional services.” Aviva Aron-Dine, a senior fellow at the left-leaning Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, has studied the issue.

“Some people with disabilities, including some kids with disabilities at more middle income levels, are optional levels for states to cover,” she said. “So those states facing big losses of federal funding may feel those are places they have to make cuts. This would be unprecedented.”

Many assume that there must be some backup option for those who would lose funding, some kind of safety net for the safety net. Aron-Dine said that is not the case.

“No,” she said, “for millions of Americans there is no plan B.”