This Athens roof has multiple problems that make it prone to leaking, including at least two skylights. Unless water is actively seeping into the rental apartment below, there’s nothing regulators can do. [Theo Peck-Suzuki | WOUB/Report for America]

A leaking roof shows the limits of Athens’ rental code

With no way to enforce an actual residential building code, the city can only act on immediate problems — not the underlying conditions that make those problems more likely.

ATHENS, Ohio — In retrospect, the SUV-sized hole that mysteriously appeared in the basement wall of the house Kim was living in should have been a warning.

Kim — a former Ohio University student who asked that her real name be withheld due to concerns about retaliation from her former landlord — contacted Athens city code enforcement. An officer came out and saw the damage, but it wasn’t until a few weeks later that her landlord fixed the hole. That seemed like a slow turnaround to Kim, but at least the problem was taken care of. She never found out how the hole got there.

The next year, Kim moved into a different building owned by the same landlord. This apartment was even worse than the previous one. A fire escape ladder gave drunk students easy access to her roof, and no one — not her landlord, not the police — could do much about it. The roof was also prone to leaking; rainwater damaged her carpet and destroyed her roommate’s laptop, and Kim worried the ceiling would collapse on her while she slept.

Kim eventually called code enforcement out to that property, as well. When she told the officer about the roof, his response stunned her.

“He verbatim said, ‘I’ve been up here. I know what it looks like,’” Kim said.

To Kim, it seemed like the officer had just admitted to some kind of negligence. The code office, after all, was supposed to ensure rental properties in the city of Athens met certain standards. A leaking roof fell below those standards — but if code knew the roof was prone to leaking, why had they let her move in? Wasn’t their job to make sure this exact thing didn’t happen?

Kim called the code enforcement office and told the person on the phone she didn’t want that officer to come back. Later, she asked the office to give her the record of his visit. Her suspicions deepened when she discovered no such record existed. It all felt like a coverup.

But it wasn’t. In fact, pretty much everything in Kim’s case followed code enforcement’s rules and procedures.

Those policies just don’t offer the level of protection Kim and other tenants might expect.

Built to fail

As soon as Athens Code Enforcement Director David Riggs pulled up a photo of Kim’s former apartment, he could see why the roof was leaking.

The first problem was the material: The roof was made with rubber membrane, which is notoriously prone to leaks if, for example, someone walks on it. This, of course, happened all the time due to the drunken students climbing the fire escape. A rooftop door also gave easy access from inside the apartment.

The photo Riggs was looking at was taken before Kim moved in, but it was clear the roof had already seen some damage. Patches of a dark, cement-like substance suggested the landlord had made scattershot repairs.

One might question the wisdom of using rubber membrane on a roof easily accessible to college students by both door and fire escape ladder. However, as Riggs noted, unwise does not necessarily mean illegal.

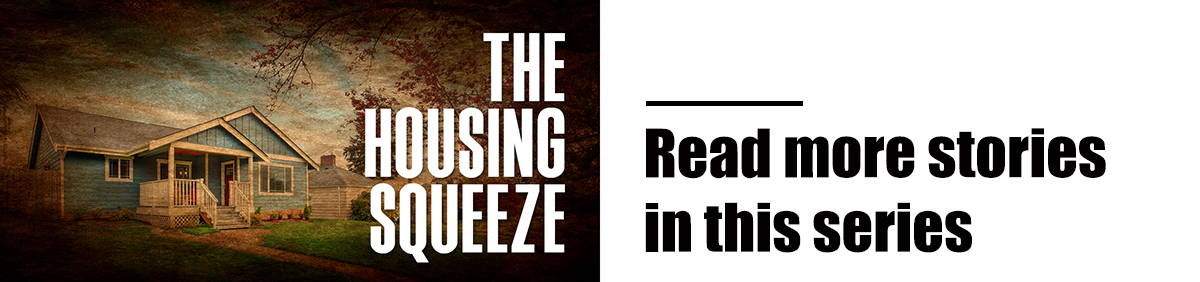

This was the most recent inspection report for Kim’s apartment at the time she was living there. The leaks began not long after.

“There’s really not a whole lot we can do,” Riggs explained. “We can keep going after the landlord if the problem just reoccurs and reoccurs. But most of our landlords, we have a decent relationship with them and we can convince them, this is not making a whole lot of sense. You’re going to spend a whole bunch more money and effort and headache trying to fix these little problems as they go along, where you really should just bite the bullet and replace the roof, or repair the door or the window or whatever.”

That’s not code enforcement’s decision to make, however. Riggs’ office can only enforce the rules spelled out in the Athens municipal code. The only rule on the roofs of residential buildings states, “The roof shall be structurally sound, tight and not have defects which might admit rain, and roof drainage shall be adequate to prevent rainwater from causing dampness in the walls or interior portion of the building.”

A rubber membrane meets that criteria. The only time it doesn’t is when it has a hole — but if landlords fix those holes, they’ve fulfilled their obligations.

“I really can’t tell the landlord, ‘You’ve got to replace that roof,’ if they continue to put patches on it and they fix the problem,” Riggs said.

The second issue Riggs saw was that the roof had multiple skylights.

“Skylights are always a bad idea,” Riggs said. “They always leak, and I don’t know that there’s any way to really, to get one that doesn’t leak.”

Nevertheless, as with the rubber membrane, having a skylight is not a violation of city code.

When Kim and her roommate moved in, they noticed one of the skylights had a large wooden box placed over it. Kim said her landlord didn’t explain what the box was for; she and her roommate found out for themselves after unwanted rooftop visitors moved it and water started getting in the apartment. It turned out the box was the only thing preventing the skylight from leaking.

Kim and her roommate complained to the landlord, who said they should call the police on the trespassers. They did, but the students kept coming back. The police told her the only way to solve the problem permanently was to have the landlord remove the fire escape. But that seemed to Kim like a fire hazard.

Eventually, the landlord attached the box to the roof. That didn’t keep the students out, but it did ensure the skylight stayed covered. For a couple of months, the leaking subsided.

The relief was short-lived. In November, the other skylights started leaking, which Kim attributed to heavy rain and snowfall. It was after this that the code officer came to visit and told Kim he’d already been up to the roof.

Kim couldn’t recall the name of the officer she spoke with, but it is clear that at least one code enforcement officer was indeed already familiar with the roof. That was Bob Mullins — the photos Riggs pulled up in his office were from him, taken during a previous visit.

On that visit, according to Riggs, Mullins found that one of the skylights was cracked and leaking. The landlord ordered the necessary parts and stopped the leak — at least temporarily. That meant no code violation.

Off the record

Riggs also explained why there was no record of Kim’s call to the code office. Typically, a record is only created for a scheduled annual inspection (Athens requires each rental to pass an inspection once a year), or when the office issues a notice of violation — the last resort, more or less, when it comes to correcting problems in a rental.

Riggs laid out the decision tree the office typically follows when it gets a call from a tenant.

“One of the things that would happen is we get a call from a tenant that says, ‘We were partying this weekend and my buddy fell down and broke a window,’” Riggs said. “The first thing the code office would say is, ‘Have you checked with your landlord?’ … For us, it’s an education process, because a lot of these students don’t know that that’s what they’re supposed to do.”

Athens Code Enforcement Director David Riggs expressed excitement that his office may soon be getting an extra staff member to address what has been seen as a shortage of code officers. “Government agencies move slow, but we are moving in that direction to try to correct those problems,” he said. [Photo courtesy of City of Athens]

Contacting the landlord is always the first step when something in a rental breaks. If no contact has been made, there’s nothing for code enforcement to do. They come in if the landlord has been informed about the problem and still won’t do anything. Riggs and others who work with tenants said many landlords are actually quite responsive and don’t let things progress to the stage where code needs to get involved.

If the tenant has contacted a landlord and nothing seems to be happening, code enforcement’s next step is to reach out to the landlord themselves.

“The inspector then calls the maintenance person and says, ‘Hey, what’s going on here?’” Riggs said. “‘Well, I ordered the window, it won’t come in for another five days.’ And a lot of times we even ask for a receipt — give me a receipt to show that you’re working on it.”

Riggs said he still doesn’t consider this an inspection. His office hasn’t had to take any formal action to compel the landlord to act. According to Riggs, filing paperwork would entail issuing a notice of violation, which in some cases might even prolong the issue.

“A notice of violation actually gives a landlord up to 45 days to do the repair. And I don’t want to make an excuse that the landlord says, ‘Well, I don’t have to work on it now. Now I’ve got 30 days for the notice of violation and 15 days for the order to comply,’” Riggs said.

In other words, if the officer thinks the landlord will make repairs, nothing gets filed. This seems to be what happened in Kim’s case, given that there’s no record of the officer’s visit in November.

That said, Kim did have the impression code enforcement gave the landlord 30 days from mid-November to correct the problem, plus another 10 to account for Thanksgiving break. Repairs slowly took shape over the next two months.

Ohio adopted more stringent building code regulations earlier this year. However, Athens Code Enforcement Director David Riggs said his office cannot enforce them because the city has no building department — though it is considering adding one in the next couple of years. [Theo Peck-Suzuki | WOUB/Report for America]

“What we would consider an inspection would be this third case where you get a call,” Riggs said. “The tenant says, ‘The window’s broken. I’ve contacted the landlord. It’s been two weeks. Nothing’s happened.’ We go out, inspect, nothing’s going on. We call the landlord, they blow us off. Well, that’s the time we do a written inspection notice of violation, order to comply, kick that in.”

Stephanie Russell-Ramos, who until April directed the Center for Student Legal Services in Athens, said her office has seen cases in which a code enforcement officer failed to document violations for which tenants had direct visual evidence.

“It is just, I mean, bad condition issues. Holes in the wall, vermin, pests, everything that you can think of that should be noted on a code report,” Russell-Ramos said.

But CSLS has never shared this information with Riggs or anyone else at the code office because tenant evidence — for example, a photo contradicting a code report — is protected by attorney-client privilege. A tenant would have to explicitly allow their CSLS attorney to share the evidence with code. Most tenants have other things on their minds by the time they get a lawyer involved.

Underpinning all of this is an issue that has dogged code enforcement for years: There are barely enough officers to conduct even the mandatory annual inspections of Athens’ rental properties. The problem came to light last year after a ceiling partially collapsed in a rental house on the city’s west side that had recently passed a code inspection.

According to Riggs, that situation may soon improve with the hiring of a new assistant code director who will join the officers in conducting inspections. Riggs said the city’s current hiring freeze will not prevent him from filling the position.

“We think that that’s an important enough position that the city really needs,” Riggs explained.

What (not) to do

By the time she saw signs of the skylights being repaired, Kim had already taken matters into her own hands: She stopped paying rent.

Attorneys who work with tenants strongly discourage doing this. State law gives landlords broad authority to evict as soon as their tenants miss rent by even a day. It doesn’t matter if the landlord in question hasn’t maintained the property. If the rent is late, nothing else matters.

The Athens pay-to-stay ordinance gives tenants more time to make up late rent, but they still have to pay.

When tenants withhold rent, they also lose the right to pursue a more effective way to hold landlords accountable: rent escrow. Escrowing rent means giving it to a court instead of the landlord. The court holds the money until it decides the landlord has made the necessary repairs.

Russell-Ramos said her office has found escrow to be highly effective with the less responsible landlords in Athens.

“We’re talking about students that have been in bad situations for six months before filing for escrow, and then within a month, most of everything that they’ve asked for has been completed,” she said.

The Athens Student Legal Services office also helps students who are having trouble getting their security deposits back from landlords. Attorney Stephanie Russell-Ramos said many students don’t know they may have legal recourse in such cases. [Theo Peck-Suzuki | WOUB/Report for America]

The problem is very few people know about escrow. This means negligent landlords can often continue not maintaining their properties. With new Ohio University students seeking housing every year amid a general housing shortage, there’s little chance demand will run dry.

“Some of the landlords will get away with what they can, and so new tenant, new opportunity to do whatever they want. We have seen several repeat landlords even for the same property, for the same issues,” Russell-Ramos said.

Russell-Ramos said she believes many of the issues regarding rental housing in Athens can be solved with better education.

“What our office is trying to do moving forward is to do more student outreach and more informational talks about housing,” Russell-Ramos said.

She said the office is also considering distributing more promotional material about rent escrow so that students are aware of the option.

For Kim, escrow was off the table because she had stopped paying rent — though by the time December rolled around, she wasn’t keen on staying in the apartment anyway. Even when the roof wasn’t leaking, it was cramped, windowless and noisy. The intrusive college students who climbed onto her roof interfered with her sleep.

“It wasn’t livable,” Kim said. “It just wasn’t an apartment that should be there, in my opinion.”

Ultimately, Kim’s CSLS attorney wrote her landlord a letter notifying him that she was terminating the lease early.

“He never really said anything back. He never really disputed it or anything,” Kim said. Nevertheless, she continued to worry that he would one day reappear to demand the rent she still hadn’t paid.

She moved into a new apartment with a different landlord shortly after the new year.