Many neighborhoods in southeast Ohio, like this one in Athens’ east side, were built before zoning codes were adopted. It raises an interesting irony about zoning: Residents who oppose zoning changes often are concerned about preserving the character of their neighborhood. But the neighborhood may violate multiple zoning codes. “That means … if your house burned down in a fire and you want to go build that exact same house on that exact same lot, you can’t without a variance,” said Shay Myers, an Athens-based architect. “And that just doesn’t make sense.” [HG Biggs | WOUB]

Zoned out: Decades-old development restrictions complicate efforts to address the region’s housing shortage

Zoning codes face increasing scrutiny as a barrier to meeting the need for affordable homes. Many communities, including some in southeast Ohio, are overhauling their codes, which can spark a backlash from residents who like their neighborhoods just the way they are.

Four years ago, developers weren’t coming to Lancaster to build housing.

The city wasn’t alone.

The global response to the pandemic left the construction industry dealing with rising interest rates, labor shortages and supply chain disruptions that drove up building costs and discouraged development.

Housing was already a problem in Lancaster, and communities throughout the country, well before the pandemic.

“We don’t have enough homes,” David Scheffler, the city’s mayor at the time, said. “The city is growing, but the roadblock we keep bumping up against is housing.”

The pandemic was making the situation even worse. And as 2021 turned to 2022 and then 2023, developers still weren’t coming to town.

“So, we decided we needed to do something,” Scheffler said. “So, we went out and started cold calling developers to say, ‘Hey, we’ve got a great town here. We’re growing. We’ve got lots going for us. Come on down and build a project here.’ Well, interest rates are high, supply costs are ridiculous, on and on and on.”

Much of what was driving up the cost of construction was beyond the city’s control. But there was something the city could do on its own to make it more attractive to developers: It could change its zoning.

Zoning codes not only dictate where housing can be built and what kinds of housing can be built, they also determine things like minimum lot sizes, how much of the lot can be built on, height restrictions and parking requirements.

These and other code requirements have a direct bearing on how much it costs to build housing, whether it’s a single-family home or a large apartment complex. Building denser and higher with less parking lowers the cost and may help a project pencil out given the other costs developers have little control over, like interest rates on construction loans, building materials and labor — costs that all rose substantially during the pandemic and still remain much higher than before.

These costs, combined with a national housing shortage, have driven up the cost of housing to the point where even middle-income earners in many communities struggle to find an affordable place to buy or rent.

In the search for solutions, zoning faces increasing scrutiny. The codes are often many decades old and seen as out of sync with the modern housing landscape and a barrier to building more affordable housing.

It’s no surprise developers might chafe against rules that restrict what and where they can build and may limit or at least complicate their pursuit of business opportunities. But zoning increasingly has come under criticism from other stakeholders, including advocates for low-income families and seniors, environmental groups, local government officials, realtors and lenders.

This has led a growing number of communities, including some in southeast Ohio, to tweak or even overhaul their zoning codes.

“All kinds of places are looking at this issue because it does in fact impact our ability to build new housing — and to build housing that meets the needs of the people who currently live in our community and people that we want to attract to our community,” said Kristen Baker, executive director of Local Initiatives Support Corp. of Greater Cincinnati, which helps arrange financing for low-income housing developments.

The city of Athens, for example, where home prices have soared over the past few years and very few new homes are being built, recently adopted changes to its zoning intended to lower building costs.

But talk of changes to zoning can ignite a community backlash. The last time the city of Lancaster tried to amend its zoning, “the NIMBYs and whatever came out of the woodwork and there was a lot of controversy,” Scheffler said. NIMBY is an acronym for “not in my backyard.”

Zoning to a large extent can determine the look and character of a community. Some residents like things just as they are and worry about how changes might affect their neighborhoods and their property values. And what often goes unsaid are concerns about the kinds of people who might move in if zoning restrictions are relaxed — the reason many zoning codes were adopted in the first place.

Dividing up communities

Visit the core of any old city in America and it’s not unusual to see homes and businesses and even old factories in the same neighborhoods. Rows of homes may share walls. Homes and businesses may occupy the same buildings, with storefronts on the bottom floor and apartments above.

In the days before automobiles and easy access to mass transit, it made sense to live close to work.

That changed as cars proliferated, combined with the rapid expansion of roads and highways. Suburbs sprang up in rings outside the city centers, especially in the years after World War II as millions of veterans with low-cost mortgages under the new G.I. Bill were looking for homes.

The suburbs beckoned with their detached homes with yards, offering more privacy and open spaces and an escape from the noise and congestion and pollution of the city centers.

“A really dominant theme of the 1950s was suburbanization and sprawl. It was just, ‘We’ll keep going further out and further out and further out and further out, and we’ve got these great cars and gas is so cheap,’” said Carlie Boos, executive director of the Affordable Housing Alliance of Central Ohio.

A new development dynamic took hold in the suburbs: Homes, businesses and industry were segregated into different zones, enforced through codes that also imposed a variety of restrictions on what could be built where.

This segregation extended to the population.

Carlie Boos, executive director of the Affordable Housing Alliance of Central Ohio, says younger people in particular are rejecting suburban life and looking to live closer to the urban centers, especially if that’s where their jobs are. “What we hear a lot of these groups say is, we want to be more walkable,” she said. [Photo courtesy of Carlie Boos]

In the older city centers, it was common to have a mix of housing in the same neighborhoods. Single-family homes might share a street or neighborhood with duplexes or triplexes or even larger buildings with multiple units.

But in the suburbs, zoning codes further divided residential areas into zones exclusively for single-family homes, zones for medium-density housing like duplexes and triplexes, and zones for higher-density housing like apartment complexes.

This had the effect of dividing communities up by income, with single-family homes often out of reach for low-income families, especially when the codes dictated minimum lot and house sizes that made it prohibitive to build homes that were more affordable.

Zoning also became a tool for racial segregation. Some early zoning codes explicitly prohibited Black and other nonwhite people from living in certain areas. But even without such language, racist hiring practices kept the nonwhite population stuck in low-wage jobs and out of the single-family residential zones.

“Zoning was created to segregate and to concentrate different kinds of housing in certain locations and goes hand in hand with redlining and all of the other sort of practices that we know have created generational wealth gaps and also have really further nurtured a lack of opportunity for folks, particularly people of color in our country,” Baker said.

Zoning codes were not limited to the suburbs. Cities and towns throughout the United States, including small, rural communities like those in southeast Ohio, adopted zoning based on the suburban models to regulate their growth.

Advocates for racial and economic justice were early critics of exclusionary zoning practices, but any talk of easing zoning restrictions, especially neighborhoods zoned exclusively for single-family homes, often ran into fierce resistance from the people who lived in them.

The growing chorus of calls for zoning reform now is a reflection of just how serious the national housing crisis has become. It has its roots in the housing market collapse that began in 2008 and never fully recovered. Since then, housing construction has fallen far short of the need at all price levels, contributing to a surge in prices that has affected a large segment of the American public.

“If you blindfolded me and put a map of Ohio up on my wall in my office and gave me three darts, and I threw three darts, I guarantee you I could hit a spot that needs affordable housing. It’s not rocket science because every place needs it,” said Wes Young, president and CEO of St. Mary Development Corp. in Ohio, which builds housing for low-income seniors.

Young said for every unit of affordable housing in the U.S., three are needed. For decades, the easiest approach to adding more housing has been to continue expanding outward, adding new suburbs into what was previously farmland or other open spaces. But some communities are starting to reach their limits, either because they’re running out of open land to spread into or what is left is not as easy to develop.

Wes Young, president and CEO of St. Mary Development Corp., which builds housing for low-income seniors, says for every unit of affordable housing in the U.S., three are needed. “If you blindfolded me and put a map of Ohio up on my wall in my office and gave me three darts, and I threw three darts, I guarantee you I could hit a spot that needs affordable housing.” [Photo courtesy of Wes Young]

The hilly terrain in much of southeast Ohio makes it particularly challenging to just keep building out. It’s more difficult and costly to run basic infrastructure, such as water, sewer and electrical lines and roads.

“We’re out of cheap land to build on,” said Shay Myers, an Athens-based architect who sits on the city’s Affordable Housing Commission. “It’s easier to do when you have an abundance of developable land. When you run out of cheap land to build on, you’ve got to start looking for other solutions other than just keep going out.”

Meanwhile, the nation is aging, with 10,000 baby boomers turning 65 every day, according to the U.S. Census Bureau. Many of them are looking to downsize or otherwise transition into some other kind of housing, Young said. But given the tight supply and high prices, combined with high interest rates, many seniors are choosing to stay in homes that are no longer the right fit for them and would be better suited for younger people with families who are also struggling to find homes.

At the same time, younger people in particular are rejecting suburban life and looking to live closer to the urban centers, especially if that’s where their jobs are. Some are tired of the increasingly congested and lengthy commutes into the city for work. Some are not interested in taking care of large homes and big yards. Some prefer the vintage and more varied architecture and overall aesthetic of city life.

“What we hear a lot of these groups say is, we want to be more walkable,” Boos of the Affordable Housing Alliance said. “I don’t want to have to drive 45 minutes to go to work. I don’t want to necessarily have to get in my car to get a cup of coffee. They’re looking for more neighborliness. And I can see that it’s … a really valid reaction to some of the extremes we’ve had in the last couple decades where it was this very severe segregation of use. We’ve had housing over here, and we’ve got business over here, and we’ve got schools over here, and never shall they mix.”

Limiting housing options

Efforts to address the housing shortage and respond to changing consumer demands often run into a wall of zoning restrictions.

“Our zoning code is not equipped to easily meet those market preferences,” said Alison Goebel, executive director of the Greater Ohio Policy Center, which promotes urban revitalization and sustainable growth.

One way to lower the cost of construction is to build smaller homes on smaller lots. But zoning codes often stipulate minimum lot sizes.

Developers have little incentive to buy a large lot and put a smaller home on it just to make it more affordable for buyers, especially given the significant increase in land costs over the past few years.

“If I have to buy an acre of land and I can only build one house on that, that cost of that one acre of land has to be absorbed by that one unit of housing,” said Amy Riegel, executive director of the Coalition on Homelessness and Housing in Ohio. “Whereas if I were able to build two, then I’m splitting that cost in half to be absorbed by the two houses. If we’re talking about multifamily, you could be splitting it across a hundred units of housing in a place like Cincinnati or Columbus.”

“And so that is where even a slight change in density on a plot of land can have a dramatic effect on how much that this house then has to cost,” she said.

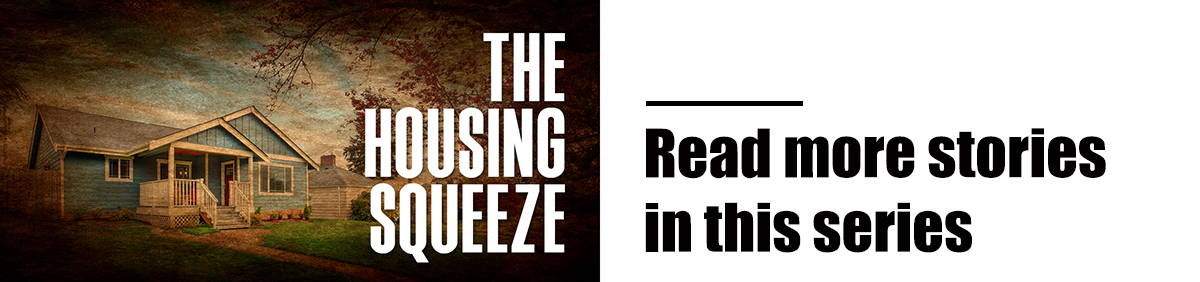

In Athens, most of the area zoned for residential is R1, which allows only single-family homes. Just a few slivers of the city are zoned R2, which allows for a mix of single-family homes and duplexes. Advocates of zoning reform say duplexes are a way to bring down construction costs and make housing more affordable without changing the character of a neighborhood very much.

Minimum lot sizes also can make it difficult if not impossible to do infill development, especially in older communities where the lot sizes were once smaller than what the codes now require. The leftover spaces scattered here and there throughout a community may just not be big enough to meet code requirements.

This is a significant problem in Athens, architect Myers said. “Athens is kind of full. When we look at the zoning map, when we look at what zoning allows, there are very few opportunities to add new housing with our current zoning codes in the city. And so that obviously creates a problem.”

Athens recently made changes to its zoning code to address this problem. These include reducing by half the minimum lot size in R1 zones, from 8,000 square feet to 4,000. R1 zones only permit single-family homes. Most of the area in the city zoned for residential is R1.

The changes also reduce lot setbacks, which specify how close a structure can be to the front, side and rear edges of a lot. This means a home can occupy more of a lot than before. In practical terms, these changes mean developers can build smaller homes on smaller lots but also can build a larger home on a smaller lot than they could before, both of which should bring costs down.

In some ways, the changes are bringing Athens’ zoning closer to what already exists. Much of the city’s housing, built before the zoning codes were adopted, does not sit on 8,000-square-foot lots. And the homes sit closer to the lot edges than what the code had allowed.

Meghan Jennings, the Athens city planner, said it doesn’t make sense to have a zoning code that puts much of the city’s housing out of compliance.

This is the case in many older cities, and it raises an interesting irony about zoning: Residents who oppose zoning changes often say they want to preserve the character of their neighborhood. But the neighborhood may violate multiple zoning codes.

“That means … if your house burned down in a fire and you want to go build that exact same house on that exact same lot, you can’t without a variance,” Myers said. “And that just doesn’t make sense.”

Another option to reduce construction costs is to build more attached housing, like the townhomes, duplexes and other arrangements common in old neighborhoods that predate the zoning codes. This not only increases the supply of more affordable housing but may also satisfy the growing demand for smaller homes and yards with less maintenance.

Attached housing by definition is not permitted in areas zoned for single-family homes. Areas zoned for higher-density housing, meanwhile, are in short supply in many communities and may be concentrated in areas that are less attractive to developers.

Zoning may also prohibit another approach to adding more affordable housing: adding another, usually smaller, residence to a lot that already has a home. These are commonly known as mother-in-law suites, but the more formal term is accessory dwelling unit. ADUs can provide low-cost housing for parents or grandparents who have retired and are looking to downsize but stay close to family.

Senior housing is in short supply in southeast Ohio and throughout the country, leaving many retirees on fixed incomes with the choice of staying in homes that are too big for their needs and too costly to maintain for their budgets or uprooting their lives and moving farther from family and their established social and community networks.

ADUs can provide an option for seniors that also frees up a home better suited for a younger family, Myers said. But they’re not allowed under the zoning codes in Athens and many other communities.

“We’re going to be displacing more and more of those people if we don’t allow new housing to happen organically,” he said. “And we can’t do that without addressing outdated zoning codes.”

ADUs also can provide more rental options for people who are not yet ready to buy a home or cannot afford one. The number of rental units is also far short of the need, especially as more people who would otherwise buy a home are stuck renting because of the shortage of homes for sale and the high costs.

On the flip side, ADUs might make it possible for people with moderate incomes to afford a home because of the rental income. And for those who already own a home but find themselves in a financial bind because of a drop in earnings for one reason or another, rent from an ADU can be a critical source of supplemental income.

Myers sees ADUs as a way to let residents become developers who might be more attuned to maintaining the character and property values of the neighborhood they live in.

Athens architect Shay Myers says some communities, like Athens, cannot simply build out to add needed housing but zoning codes often make it difficult to do infill development. “When we look at the zoning map, when we look at what zoning allows, there are very few opportunities to add new housing with our current zoning codes in the city. And so that obviously creates a problem.” [HG Biggs | WOUB]

Vacant office buildings, shuttered factories and other commercial structures with available space also present opportunities to create more housing. These conversions may include some combination of retail or office space at street level and living space in the upper floors. This may appeal in particular to those looking for an unconventional apartment or condo close to the urban core with minimal maintenance.

In some cases these structures may be long abandoned, run down and a community eyesore, generating little tax revenue for the community. But zoning codes at their most basic level create separate residential and commercial districts, and may not allow the two to coexist without some kind of exception.

These conversions may also run into other zoning obstacles, including parking requirements tailored to a more car-centric suburban lifestyle.

Minimum parking standards were built into zoning codes to ensure enough spaces are available for people to park close to where they live and work, so they don’t end up encroaching on someone else’s space. But advocates for zoning reform say a more flexible approach is needed at a time when the housing supply is falling short of the need, building costs are high and developers are having to get creative.

“Before some of these codes took over, what you saw is, people could build the kind of home that they needed,” Carlie Boos of the Affordable Housing Alliance said. “If you want a parking spot, rock on, you should be able to have ’em. But we’ve lost that nuance where if it’s not something that you as the consumer want, you no longer have a choice to skip it.”

Wes Young of St. Mary Development Corp. said parking minimums are often a barrier to building affordable housing. Rising construction costs have made it difficult to build housing for seniors on fixed incomes and other lower-income people without tax credits. But these credits do not cover the cost of land, and buying enough land to meet the parking requirement may make it impossible for a project to pencil out.

“I think we have to make a decision as a community, are we going to invest in more parking or are we going to invest in people, invest in housing?” architect Myers said. “And you can’t always have both. So that’s a big issue with our current zoning codes, our parking minimums, and it’s an issue with a lot of zoning codes. Cars take up a lot of space, and when we’re having to sacrifice density for surface parking, that’s just another limit on the amount of housing that we can add to the community.”

Working around the code

There is a workaround to all these zoning challenges.

Developers and others looking to build or renovate something that runs afoul of zoning codes can seek a variance.

This is a formal process that usually involves some kind of board or commission that reviews the requests and decides whether to grant them.

In Athens, for example, variance requests are taken up by the city’s Board of Zoning Appeals, on which sit community members appointed by the mayor.

The board’s hearings are public and anyone can show up to testify for or against granting a variance. This allows a community to evaluate exceptions to the zoning code on a case-by-case basis.

Kristen Baker, executive director of Local Initiatives Support Corp. of Greater Cincinnati, says while variances are a way to get around zoning restrictions, they add uncertaintly, delays and increased cost to projects. “It severely limits the number of developers that can actually do projects,” she said. [Photo courtesy of Kristen Baker]

For developers, or even homeowners looking to build an addition or add a front porch, getting a variance adds more cost and uncertainty to a project.

For example, an attorney with expertise in zoning may be needed to help navigate the process. It can take weeks or months to get a variance, which can lead to more delays depending on changes in the weather. In the meantime, the cost of building materials and labor might increase, adding to the cost.

At the end of the process, there’s no guarantee the variance will be granted, and this uncertainty can make it more challenging to line up financing for a project — lenders are famously risk averse — or to line up contractors and other workers.

“What we see in a world of variances is that there’s no real rhyme or reason to what does get passed and what doesn’t get passed,” said Amy Riegel of the Coalition on Homelessness and Housing in Ohio. “And that is a risk that just then makes developers less comfortable with operating in that area or may make investors fearful that their investments aren’t safe in that area.”

This can make it particularly difficult for small, local developers operating in smaller communities, Kristen Baker of Local Initiatives Support Corp. of Greater Cincinnati said.

“It severely limits the number of developers that can actually do projects,” she said. “Because if I’m an entrepreneur and I want to get into real estate development, and I live in some small community and I want to do something in that small community to support my neighbors and to build some new housing, you then have to go through all of those hoops and complicated steps, and that costs money, that costs time.”

If it reaches a point where many or even most projects require variances, this is likely a sign the zoning codes are outdated. The result is development by variance, which, advocates of zoning reform say, not only discourages development but is a terribly inefficient way for a city to do business.

“It becomes the standard, and it shouldn’t be the standard. And it places a large administrative burden on the city,” said Meghan Jennings, the Athens city planner.

In older neighborhoods where lot sizes are already smaller than what the code requires, anyone wanting to add a porch or build an addition has to get a variance, Jennings said. Variances, she said, should be for the relatively rare and unusual situations, not routine projects.

But in Athens, so many older homes do not meet code that almost any project is going to require a variance.

“If you can’t even do a room addition on a home in the near east side without having to require a variance, that property’s not the problem, the code is the problem,” Jennings said.

Understanding the opposition

Efforts to change zoning codes can run into strong opposition from residents.

“I’m not an elected official, but I got shouted at and really threatened essentially by angry residents who, when speaking about this issue or when talking about why zoning reform is necessary to the health and growth of our community and for our neighbors to be able to have housing, I got shouted down,” Baker said. “And our political officials face that times a hundred, and personal threats and the whole nine, because people are so scared of change and zoning reform represents change.”

Opposition to zoning changes can be particularly intense when it comes to building more affordable housing, in particular apartment complexes and other forms of multifamily housing. Opponents often will raise concerns about preserving the character of their neighborhoods and their property values, about traffic impacts and the fear that lower-income residents will bring more crime.

Amy Riegel (standing at podium), executive director of the Coalition on Homelessness and Housing in Ohio, says when making changes to zoning codes it’s important to understand why this might raise concerns. For many people, their home may be the only significant asset they own. “It can risk people’s financial security, their personal security. And so it bubbles up a lot inside of people.” [Photo courtesy of Amy Riegel]

“This is something that we face a lot, is that the zoning codes are protective armor for a lot of neighborhoods,” Riegel of the Coalition on Homelessness and Housing said. For many people, their home may be the only significant asset they own. They may be counting on the equity to help with a move someday, or for retirement, or just for the peace of mind in having a financial cushion.

“And when you change the rules around where that property exists,” Riegel said, “it can put those things at risk. It can risk people’s financial security, their personal security. And so it bubbles up a lot inside of people.”

Another concern that may go unspoken reflects one of the original intentions, or at least consequences, of zoning, which was to segregate people.

“If we have affordable housing, then there’s going to be, and I hate to say it, but there’s going to be those people coming in. … I don’t want that. I want it to be the same. I don’t want different ethnicities or whatever. I don’t want that in my town,” Wes Young of St. Mary Development Corp. said.

Advocates for zoning reform say while it may be tempting to dismiss the opposition as just naked NIMBYism, these concerns should be addressed in a meaningful way in any effort to make significant changes.

“Zoning codes should not be updated in a bubble,” Riegel said. The process should include ample opportunity for public input and discussion, and out of that process, she said, “can come out clear understandings of what the community intends to be, and what they want to be, and how that can be achieved.”

“There’s no single universal answer for each city,” Carlie Boos of the Affordable Housing Alliance said. “It’s going to be city by city, community by community. It’s going to be based on the values and the needs of whatever that local environment is.”

“I think the only thing I would say as a universal,” she said, “is if you are in a city and your zoning code has not been comprehensively assessed in the last 30 years, chances are it’s not meeting today’s problems.”

For those who like their communities just as they are and aren’t anxious to see more change or growth, these barriers to development may not seem like such a problem.

But there are tradeoffs. If a community is desirable enough, a lack of development won’t stop people from trying to move there. And this demand coupled with a limited housing supply will drive up costs, possibly past the point longtime residents can afford.

Athens City Planner Meghan Jennings and other advocates of zoning reform say code restrictions also limit economic development if communities cannot provide enough or the right mix of housing employers need for their workers. “We are limiting ourselves — not just housing, but also economically. And that’s a problem,” Jennings said. [HG Biggs | WOUB]

Talk of zoning reform often comes up in the context of providing more housing for people who need it. Reform advocates say it can also be a central piece of economic development. Many rural communities in southeast Ohio are steadily losing population. As the population shrinks, so does the tax base and the ability of local governments to provide basic services. Without enough customers to sustain them, businesses close.

Economic development officials in southeast Ohio say they pass up on opportunities to recruit the kinds of employers they’d like to see in their communities because they lack enough, or the right mix, of housing to match the jobs that would be created.

Without zoning reforms that would promote the needed housing, “we are limiting ourselves — not just housing, but also economically. And that’s a problem,” Meghan Jennings, the Athens city planner, said.

“Athens is fairly landlocked,” she said. “We’ve got steep slopes and we’ve got floodplain. And so the amount of land that we really have available in order to provide the housing and the commercial uses for the population that want to move here and the jobs that we want to be able to provide, we have to use the land that we do have as efficiently as possible for sustainability reasons, for the city’s economic budgetary reasons.”

‘It’s our families. It's our neighbors’

Given the length and depth of the nation’s housing crisis, some communities are finding people are becoming more receptive to zoning changes as a way to add supply, bring down costs and stimulate economic development.

“In one generation, we’ve seen this insane dip in affordability,” Boos said. “So it is a relatively new problem that we are trying to solve for, but there have been cities that have been really concerned about population loss and depopulation and the loss of economic activity and opportunity, and they’ve been using their zoning code to attract new residents with a ton of success by kind of leading with that quality of life argument.”

David Scheffler, the former Lancaster mayor who helped lead the city’s zoning overhaul, said that while the previous effort to change the city’s zoning had run into stiff opposition, this time around city leaders faced surprisingly little resistance.

He’s not sure why. But the results of the zoning reforms have been exactly what he had hoped. No sooner were the changes made than developers started expressing interest in the city again, and several housing projects are now underway.

Some may understand the need for more housing, but worry that zoning changes will just enrich developers and not address the affordability problem. Developers could just end up using the relaxed zoning restrictions to build more homes but keep charging high prices for them.

Advocates for affordable housing say these concerns are misplaced.

“The profit margins are not what I think people think they are,” Kristen Baker of Local Initiatives Support Corp. of Greater Cincinnati said. “So you hear people often talking about developers very disparagingly, at least in our region, like, ‘Well, these developers are just making all of this money.’ And the reality is, as someone who actually is in the finance sector, when we evaluate their project finances, they’re not coming away pocketing that much cash.”

The fundamental problem in the housing market is basic supply and demand: not enough housing to meet the demand, which drives up prices.

Increasing supply should help ease housing costs, at least with housing for middle-income earners. But zoning changes alone may not be enough to get more low-income housing built. This housing doesn’t cost that much less to build, and given the much higher costs for materials and labor in recent years, these projects typically do not pencil out without some other incentives.

The most common are tax credits. But even with these credits, the margins can be thin, so developers typically are allowed to charge market rate for a certain percentage of the units in a housing complex, and the rest must be rented to people whose incomes fall below a certain percentage of the area median income.

Boos and other affordable housing advocates say they have no problem with developers turning profits from low-income housing.

“I think, at least, it’s important for us to continually remind ourselves, developers are not the end users of this thing,” Boos said. “Developers are not going to be living in those homes. It’s us, it’s our families, it’s our neighbors. Developers are just the vehicle that gets us what we need as a community. I’m never going to attack a doctor for trying to cure cancer ’cause he might make a buck off of it. I still want to cure cancer.”