News

Palliative Care Still a Challenge for Many (interactive map)

By: Kelvin Suddason | SHFWire

Posted on:

WASHINGTON – For patients needing palliative care, a specialized medical care for those with a serious illness, they now have less than a 50 percent chance to get access to it. In a state like Wyoming, their chances drop to one in six.

The United States recently received yet another B rating, as it did in 2011, from the Center to Advance Palliative Care, for its overall performance regarding the provision of palliative care. While a B rating may seem satisfactory, the data say otherwise.

According to the National Institutes of Health, palliative care is different from hospice in care in that it is a “comprehensive treatment of the discomfort symptoms and stress of serious illness.” This medical specialty seeks to help chronically ill persons with diseases such as cancer, kidney disease or dementia.

A palliative care team can involve psychologists and family therapists for emotional support, health-care coordinators to ease the administrative process and nutritionists, among other specialists focused on improving quality of life. Hospitals that offer a palliative care program can be found on the Get Palliative Care website.

The 2015 State-by-State Report Card on Access to Palliative Care in our Nation’s Hospitals, produced by the Center to Advance Palliative Care and National Palliative Care Research Center, was published on Thursday.

The report found that there has been a continuous rise in the number of hospital palliative care teams across the U.S. The number of states with more than 80 percent of hospitals offering palliative care doubled between 2011 and 2015, causing the number of states graded A to jump from eight to 17.

But while there are no states failing this year, the report shows that there is still work to be done.

Despite a 4 percent increase between 2011 and 2015 in the number of palliative care teams in hospitals with 50 or more beds, and 90 percent of large hospitals providing such services, it seems that hospitals overall are not meeting the palliative care needs of seriously ill patients.

On average, of those patients admitted to hospitals who need palliative care, less than half were able to receive such medical care. According to the report, between 1 million and 1.8 million patients every year who could receive palliative care were not benefiting from such services.

This underperformance by hospitals is due to an insufficient workforce, a consequence of palliative care being a new medical specialty, Sean Morrison, director of the National Palliative Care Research Center, said. A lack of funding has also been a major barrier.

“Palliative care training spots in the country are funded by private sector philanthropy. There is not Medicare funding for specialty training,” Morrison said. He said that, because palliative care is a new specialty, a third of all states do not yet have training programs for this specialized medical care.

As a result, the study found that “hospital palliative care teams are often overstretched and unable to see every hospitalized patient who could benefit from their services.”

Morrison said this trend can be reversed at medical schools.

“Core palliative care knowledge and skill training need to be integrated to regular medical school and graduate medical education,” Morrison said.

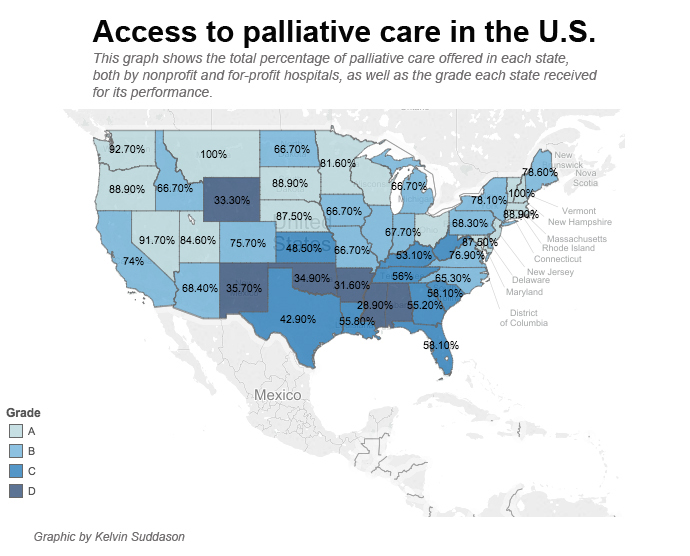

There are also wide gaps in terms of access to palliative care among states. For instance, the District of Columbia scored a B with 71.4 percent of hospitals offering palliative care. But in West Virginia, only 55.6 percent of hospitals offer such care.

The report found that the south-central region is the one that needs improvement in its palliative care services. Alabama, Arkansas and Mississippi have among the lowest levels of access to palliative care services. In contrast, all hospitals in New Hampshire, Vermont and Montana have palliative care staff.

The report found that “for-profit hospitals of any size are less likely to provide palliative care services than nonprofit hospitals.” States with high percentages of for-profit hospitals ranked poorly in terms of palliative care provision.

The data shows that A-graded states report extremely low numbers of for-profit hospitals, while the lowest performers, with grade D, report relatively higher numbers of for-profit institutions. On average, an “A” state has about one for-profit hospital versus about nine for-profit hospitals in a “D” state.

“Differences in palliative care availability in for-profit as compared to nonprofit and public hospitals are unknown,” the report said, given that palliative care is associated with lower hospital costs.

Hospitals could save thousands in providing palliative care. Despite a preference for comfort and relief care, many chronically ill patients receive low-yield, burdensome and high-cost tests and treatments, including prolonged stays in intensive care units. Palliative care would discontinue these costly, non-beneficial and often unwanted interventions.

According to another study published in 2008, palliative care service could lead to a reduction in direct hospital costs of almost $174 per day for patients discharged alive. For an average 400-bed hospital offering palliative care to 500 patients a year, the net savings could amount to $1.3 million a year, even after removing physician revenues and extra personnel costs.

That study, Cost Savings Associated with US Hospital Palliative Care Consultation Programs, conducted by Morrison, has confirmed that hospital palliative care is associated with significant hospital cost savings.

“Palliative care is one of the few areas of medicine that has been shown to achieve the triple aim of health care: better care, higher satisfaction with care, at lower cost,” Morrison said.

This story is courtesy the Scripps Howard Foundation Wire. Reach reporter Kelvin Suddason at kelvin.suddason@scripps.com or 202-408-1494. Like the SHFWire interns on Facebook and follow them on Twitter and Instagram.