News

Opioid High: Students Face A Different Kind of Test

By: Aaron Payne | Ohio Valley ReSource

Posted on:

It’s not just about notebooks and pencil boxes anymore: the opioid epidemic means back-to-school supplies now include things like emergency overdose treatments and drug prevention plans.

Many schools in the Ohio Valley region are using random drug testing despite doubts from addiction treatment experts about whether the tests really work to deter abuse.

A Tragedy, Then Testing

A new testing program takes effect this year in Belpre, Ohio, where students have witnessed the consequences of opioid abuse first hand.

On a recent Friday night, the Belpre High School football team made the trip to face Trimble in the second week of high school football.

Among the team leaders are Logan Racy and Aric Ross, who are both in their senior seasons.

Taking on the role means being good role models on and off the field, according to Ross. And that includes remaining opioid free.

“Practicing with these guys everyday, you get really close. You’re all friends, it’s a brotherhood. You don’t want to let the other person down,” he said. “You don’t want to be the person that got busted for drugs.”

Racy agreed, and said the love of the game is a good deterrent.

“If you have a passion for the sport and a love for it, you’re going to stay away from that stuff.”

The two are not alone. A recent study from the Journal of the American Academy of Pediatrics found students who participate in extracurricular activities were less likely than their peers to have long-term opioid use disorders.

This doesn’t mean student athletes are immune to the dangers of opioid abuse, as Racy and Ross understand

Two years ago, a teammate died of a heroin overdose the summer before his senior year.

“The morning of the practice when coach broke the news, we were all very surprised and shocked,” Racy said. “It was heartbreaking.”

The death was hard for the students and the educators working in the Belpre City Schools system.

“To lose a kid to anything is tragic,” superintendent Tony Dunn said. “To lose a kid to something as preventable as an overdose, an accidental overdose, is devastating.”

A committee of adults joined student athletes like Logan Racy in response to the tragedy and established a random drug testing policy. Middle- and high-schoolers involved in extracurricular activities or who drive to school are tested.

Students who violate the program are given up to three strikes. Upon each infraction, the student is brought in for counseling and faces increasing punishments from suspension from extracurricular activities up to a ban on participation.

The program may not keep every child from abusing opioids, but Dunn said the schools needed a way to reach the kids suffering from addiction. And by providing treatment and counseling for those students rather than expelling them, they hope to prevent the next tragedy.

“The ultimate success will be none of our kids will die from accidental overdose,” he said.

“Give Me A Reason”

Another drug prevention program in West Virginia also uses drug testing kits but hands the responsibility of administering them to the parents.

The office of the U.S. Attorney for the Northern District of West Virginia set up a booth at a recent match-up between the reigning AAA division champions in Wheeling Park and the reigning AA division champions Bridgeport as part of the “Give Me A Reason” program.

U.S. Attorney Bill Ihlenfeld helped pass out the saliva-based kits –which are funded through the federal Appalachian High Intensity Drug Trafficking Area program– to parents as a means to give kids a reason to reject drugs.

“They can honestly look their peer in the eye, their teammate, their quote-unquote friend and tell them ‘I can’t use that because my parents drug test me,’” he said.

The tests are also meant to start a conversation. The Partnership for a Drug-Free America claimed in 2008 that “teens who learn a lot about the risks of drugs at home are up to 50 percent less likely to use.”

Since the program’s inception in 2014 for the four Appalachia HIDTA states (Kentucky, Tennessee, Virginia and West Virginia) West Virginia has handed out approximately 2,500 of the total 7,000 kits distributed.

But as those tests appear in more homes and schools, there are big questions about what effect they have.

“It Just Doesn’t Work”

Dr. Steven Matson, Chief of Adolescent Medicine at Nationwide Children’s Hospital in Columbus, Ohio, is among those who oppose the use of drug testing outside of medical settings.

“People have looked at that random drug testing and it just doesn’t work,” he said. “You might get somebody to be careful if they’re an athlete, which isn’t a terrible message. Often by the time you’re getting to high school, patterns are already set.”

Many pediatricians agree and the American Academy of Pediatrics repeatedly calls for drug testing only in medical situations. The Society points to studies on school testing programs which have shown mixed results.

Matson also runs an addiction clinic at Nationwide Children’s Hospital, working with clients aged 14 into the late teens.

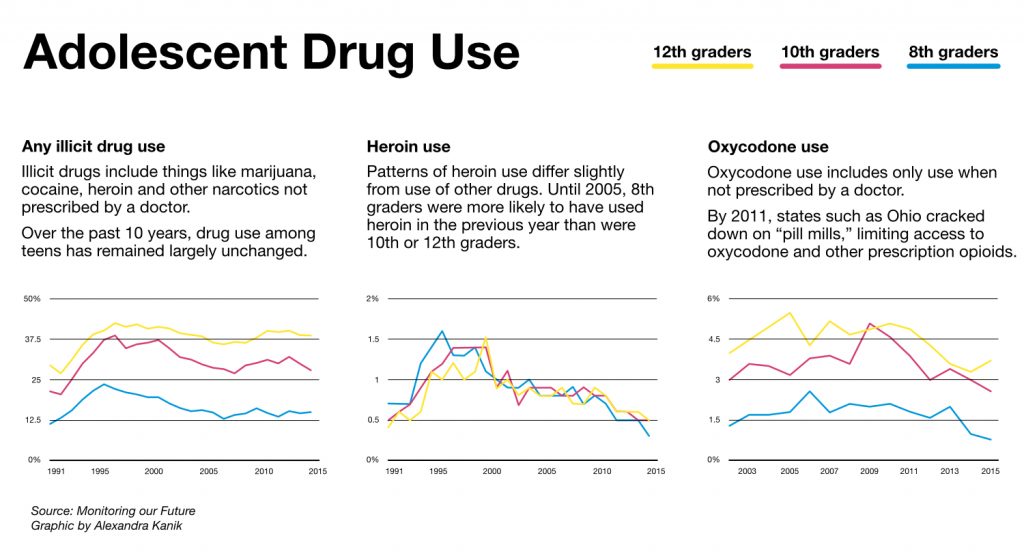

Alexandra Kanik | Ohio Valley ReSource

Alexandra Kanik | Ohio Valley ReSourceDrawing on his experience with teenagers, he said he believes that parenting a child is a better way to keep them drug-free than drug testing them.

“You might make your kids crabby for a little while. But that’s your job as a parent to not always be their best friend.”

Researchers for the Journal of Psychiatric Studies last year found children who receive direct involvement from their parents are less likely to abuse opioids.

When asked for his “best practices” at home for parents, Matson’s recommendations include the following:

- Set the expectation of a drug-free lifestyle for the child and clearly state that.

- Have conversations about drug abuse based in love, rather than fear.

- Get to know the child’s friends.

- Make a point to spend time together as a family.

- Offer the child unconditional love.

Do No Harm

Matson said the medical community also plays a role in limiting access to the opioids children might abuse, especially prescription painkillers.

His colleague Sharon Wrona, Administrative Director of Pain Management at the hospital, works to develop best practices when it comes to treating young patients with opioids.

“If we’re prescribing opioids, certainly you need to weigh the benefits and the risks,” Wrona said. “And you need to see if it’s appropriate for that type of pain.”

Environment, previous medical history, and family history with opioids are just some of the factors physicians are paying closer attention to.

To keep opioid prescriptions at a minimum, physicians are first recommending treatments such as aromatherapy, physical therapy, and acupuncture.

Teaching children and their parents to manage pain at home is also a priority for Wrona’s team. She said one of the more effective lessons comes through gamification.

“We can hook them up to a machine that has a sensor, and it measures their body temperature and their sweat and things like that,” she explained. “There’s, like, a game in there and it shows them they can move through the game if they’re relaxing and using the techniques that we taught them.”

Promising Trends

Statistics show these efforts might be paying off.

In Ohio, the number of solid opioid doses distributed by doctors in 2015 fell by 81 million compared to 2011, according to new data released by the state’s Department of Health.

Elsewhere, data from the group Monitoring the Future indicates that opioid abuse has dropped over the past few years among 8th, 10th, and 12th graders.

Most experts believe if enough resources go toward proven prevention and treatment programs, healthy children will grow into adults with a better shot at ending the epidemic.