Culture

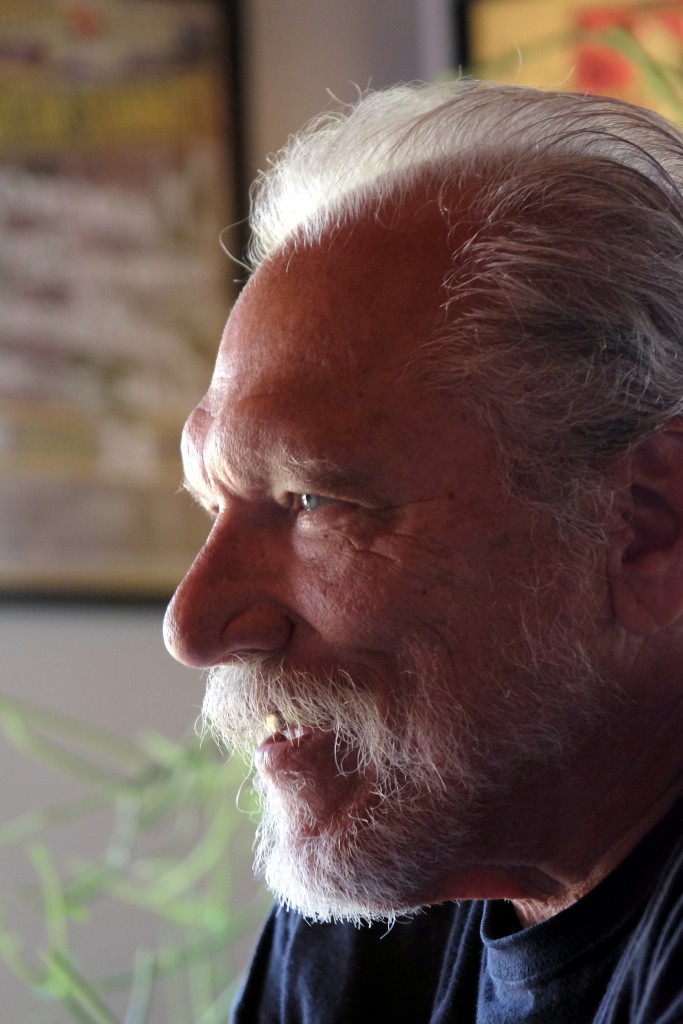

Talking the Summer of Love with Jorma Kaukonen

By: Emily Votaw

Posted on:

It’s a balmy day in late June, and Jorma Kaukonen has invited WOUB onto the grounds of his Fur Peace Ranch, a sprawling compound dotted with little gardens and rustic cabins that is known best for its prodigious guitar camps.

“We’re in Southeast Ohio, so I don’t have to tell you – we’re a destination, not a waypoint,” said Kaukonen. “The funny thing is, for a long time I was sort of the attracting factor about the place; but now people come to the guitar camp who don’t even know who I am – which I think is fantastic.”

As a founding member of both psychedelic rock forerunners Jefferson Airplane and blues rock pioneers Hot Tuna, it’s safe to say that anyone who knows music is going to recognize Kaukonen, who has lived in the gentle foothills of Meigs County for the past 30 some years.

Born in 1940, Kaukonen is a second-generation immigrant, a rock ‘n’ roll legend, and one of the few people who lived through the Summer of Love on Haight-Ashbury in 1967 who is still around to tell the tale of the magical, bizarre migration of some 100,000 young people to San Francisco over the course of about five months 50 years ago.

Tuesday, July 25, WOUB-HD is airing Summer of Love: American Experience, a documentary that explores the social phenomenon of the hippie movement within the confines of that strange summer and its lasting impact on the world that we live in today.

“Who knows why stuff started to happen in San Francisco in the late ‘60s,” said Kaukonen, who moved to San Francisco in 1962 to enroll in Santa Clara University and teach the purist, classic blues guitar that he is famous for. “There were a lot of talented artists all in one place. At the time, we were just the kids who were playing music around there – Jerry Garcia and Janis Joplin and so many other people. When I moved to San Francisco, hippies didn’t really exist yet. It was sort of this interesting, post-beat-generation time.”

Kaukonen said that he often thought of San Francisco through the lens of hard-boiled detective novelist Dashiell Hammett – as foggy, obscured, and ultimately quite noir – quite the far cry from the colorful photos of Haight-Ashbury taken in the late ‘60s.

“Eventually the Grateful Dead started up, and then the (Jefferson) Airplane got a record deal, and for some reason, people started to take notice of San Francisco,” said Kaukonen, citing a March 1967 TIME piece that highlighted the area and its blossoming cultural scene as a part of the reason why thousands of young people descended to the streets of San Francisco that summer. “It’s interesting, because the summer in San Francisco can be sh*tty, but in ’67, it was one of those magical summers where it was perfectly temperate. You could live on the street, and many people did.”

“Who knows why stuff started to happen in San Francisco in the late ‘60s. There were a lot of talented artists all in one place. At the time, we were just the kids who were playing music around there – Jerry Garcia and Janis Joplin and so many other people. When I moved to San Francisco, hippies didn’t really exist yet. It was sort of this interesting, post-beat-generation time.” – Jorma Kaukonen

Although Jefferson Airplane wasn’t huge in 1967, they were on the precipice of major mainstream success – only months off of the February ’67 release of their debut album, Surrealistic Pillow, the band already had two singles that would go on to become iconic – “White Rabbit,” and “Somebody to Love.”

“By ’67 we were all actually making money – we paid rent and had cars, so I wouldn’t really say that we were a part of the hippie community at that point,” said Kaukonen. “There was definitely a magic moment of community in San Francisco before everyone came – and I think that is because the community was pretty small. All the writers and musicians and everyone knew everyone else. When all these people came into town, that changed things – suddenly you didn’t really know everybody anymore. In my opinion, that is one of the things that sounded the death call to the whole thing – we weren’t a tight-knit community anymore.”

“You know, the funny thing about anything commercial is that if you give it a name, it will live forever,” he said. “It’s kind of humorous to me at this point, the Summer of Love – because it is a part of my personal history and of American history in general. People say ‘oh, that will never happen again,’ and they’re probably right because it was a different time. Back then, things seemed pretty simple. We worried about civil rights. We worried about the war. Now, people need to worry about climate change; about fracking; about politics.”

At heart, Kaukonen has always been a bit of a geek. For most of his life he has maintained an encyclopedic knowledge of purist blues music, a tradition that he is known for performing above all else. Although he allegedly never intended to get involved in a rock ‘n’ roll band, when he was introduced to the now archaic tape delay machine, he was hooked on what he could do “if he plugged in a guitar.”

Now, Kaukonen is passionate about many things, among them his family, playing guitar, riding his motorcycle, but, most recently, drones. The kind that take gorgeous aerial shots of the world – a kind of technology that Kaukonen said that he only dreamt about as a child.

“I’ve always liked technology – in the ‘80s I went out and bought a computer when they were still very new, and even though I was never an expert at it, I just thought that it was fun,” said Kaukonen. “It’s the same way with these drones, although I do plan to get a commercial license at some point. More than anything, these things can just take amazing pictures.”

One way Kaukonen naturally experimented with drone footage was with the documentation of his live performances, a number of which he has photographed aerially with his drone, which was given to him for his birthday last year by his wife and daughter.

In addition, Kaukonen has been working for the past several months on a forthcoming memoir, something that he said he was within hours of finishing when WOUB stopped by his property.

He said that even though he’s been a writer all his life, working on the memoir proved difficult in its own way.

“As a songwriter, unless I am driving a car, if I get inspiration for a song, I sit down immediately and write it down, because otherwise I’ll forget it like it never happened,” said Kaukonen. “But with this project, I wasn’t really looking for a muse like that. I had to make the writing process itself the muse, and that is definitely what has been working for me.”

Before WOUB leaves the ranch, Kaukonen pulls out his drone to demonstrate its skills. He pops open the back of his truck, fetches the drone, and it takes off into the clear summer sky. It’s a Sunday, and the ranch is closed to the public, but, typically, there is a buzz to the place – a place that is a guitar camp, a pho restaurant, a live music venue, and, last but not least, the place where Kaukonen has lived with his family for many years.

“Because of the nature of my work, my life is kind of quasi-public anyway,” said Kaukonen. “When we are having the guitar camps, everybody is here for the same purpose. So there is that sense of community, it’s something that some people get and others just don’t get. At this point, I don’t really have any secrets – so – and this sounds so geeky – if there is some way that sharing my life with the world will brighten it, that’s something that my family and I are good with.”