News

Report Reveals Contaminants In “Legal” Water

By: Nicole Erwin | Ohio Valley ReSource

Posted on:

An environmental group’s new report shows a broad range of contaminants occur in many drinking water systems in the Ohio Valley, even though the water meets federal requirements. The research highlights the gap between what regulations require and what many scientists and health advocates recommend for safe drinking water.

The Environmental Working Group compiled the report from data it collected from more than 50,000 public water utilities across America. The EWG created a scale based on the most stringent health standards and latest science and research at one end (like the California health standards which are generally more protective of health), and federal guidelines at the other. The online tool EWG created shows where a water system’s detected level of contaminants falls in that range.

“Legal doesn’t necessarily mean safe. And just because there’s a legal limit for the contamination doesn’t mean that’s the ideal level or the safe level, necessarily, of that contaminant,” EWG senior scientist David Andrews said.

At the Source

Paducah Water, located on the confluence of the Ohio and Tennessee Rivers in west Kentucky, is among the many regional water systems in the report. General Manager Bill Robertson stood among the pumps sending freshly treated water out into the city’s system of pipelines.

“The water is at its best quality when it leaves here; and it has to go up the pipes to go to the pumps,” Robertson said. “It has to go through tanks and it has to go through your plumbing at your house and it can only do one thing, and that is to degrade.”

But clean as the water is at this point, the EWG report identified contaminants in Paducah’s water that could pose health risks, even though the water system meets legal standards.

Water sampling data from 2010 and 2015 show five chemicals in Paducah water that the EWG says could increase risks of cancer and other health issues if users are exposed over long periods of time.

Robertson read from the group’s data.

“So what do we have? Atrazine…Atrazine is everywhere. Atrazine is pre-emergent herbicide farmers use,” Robertson said.

He said the chemical is less present now than it used to be because farmers are more diligent in application. But it is still common in water.

More than Monitoring

There are at least 30 contaminants the EPA has flagged for monitoring under the agency’s third Unregulated Contaminant Monitoring Rule. Every five years the contaminants on the list are reviewed according to what may be present in drinking water. The data collected are used to inform regulatory decisions. Chemicals such as chlorate, which is used to disinfect water, are monitored through the unregulated contaminant water rule.

“Chlorate can come from a lot of places. It can come from explosives, it could come from fireworks. It can come from degradation of sodium hypochlorite, which is bleach,” Robertson said.

According to the EWG the Ohio Valley is riddled with wastewater treatment facilities, energy companies, and chemical plants that discharge contaminants that often show up in water systems. These can be pollutants used in industrial processes or the byproducts of disinfectants used to treat waste.

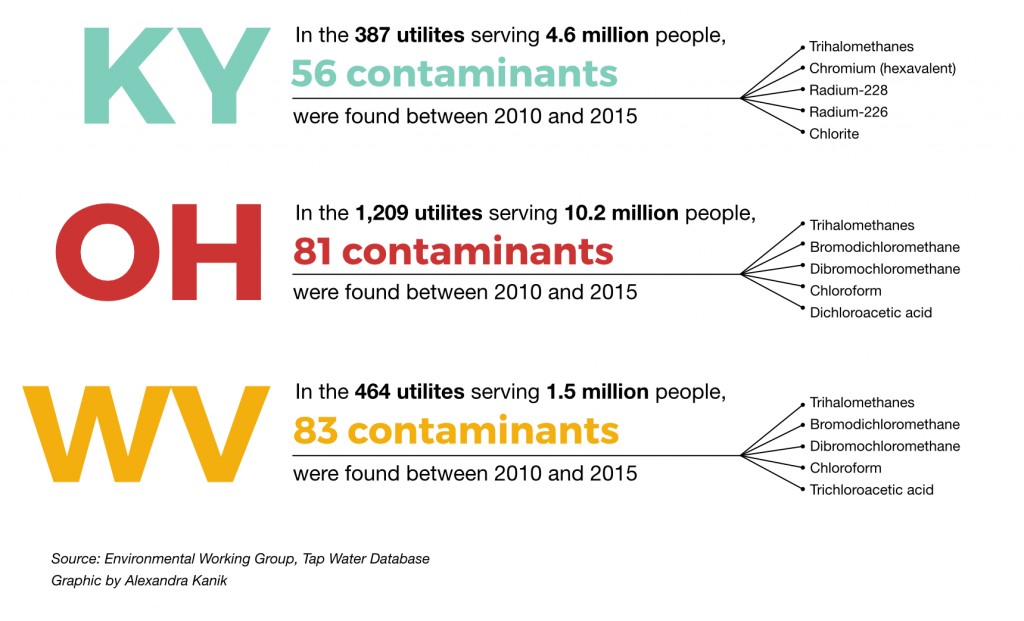

The EWG site shows West Virginia with the most contaminants, with 83 chemicals flagged between 2010 and 2015. Ohio has 81 and Kentucky showed 56 contaminants.

EWG’s Andrews said the EPA is “woefully behind in setting new regulations for emerging contaminants.”

Info On Tap

The EWG online tool allows anyone who relies on a community water system to enter a location to get results specific to a water system. For each of the drinking water contaminants found in that water source, the EWG identifies the legal limit, if one exists, and a health based limit derived from best available science and protective state standards.

One frequent contaminant Andrews highlighted is hexavalent chromium, also sometimes called Chromium-6. He calls this the “Erin Brockovich contaminant” after the activist who brought attention to contamination in the Southern California town of Hinkley, and who was the subject of the eponymous 2000 film.

The EWG site places the health-based limit for hexavalent chromium at just 0.02 parts per billion, an extremely small measure. “This is based on concern that ingestion could cause stomach cancer or intestinal cancer based on actual federal testing of animals,” Andrews said.

But despite those health concerns, Andrews said, the EPA standard is far weaker, and the agency has been unable to upgrade its standards on the chemical over the past decade or even to complete a scientific review of this chemical.

Andrews blames pushback from industry lobbyists for slowing the review of the regulation.

That includes the electric power industry. The chemical was used in cooling towers and in electricity generation.

“Then there’s also been pushback from the chemical industry that has used this in everything from chrome plating to treatments for leather, wood and other materials,” Andrews said.

Andrews said the EWG is “trying to really just provide a resource that enables everyone across the country to become more educated about their drinking water.”

Consumer Confusion

The world of water treatment is complex. Environmental consultant Marc Glass, who works with Downstream Strategies in Morgantown, West Virginia, said that nearly every water system he has looked at has had at least one of the disinfection byproducts the EWG report calls attention to.

“And that’s due to the sort of nexus between protecting against the long-term risks and short-term risks,” Glass said. Job number one, after all, is to disinfect water so that consumers won’t get sick. That’s the short-term. But in the long-term, some of the disinfectants can produce byproducts that carry other health risks.

Kentucky Energy and Environment Cabinet Spokesman John Mura has a problem with how EWG presents the information.

“It is misleading,” he said. “They’re pairing Kentucky’s levels with California guidelines when we are held to maximum contamination levels set by the EPA.”

Mura doesn’t want people to think that the state’s water is unsafe. He said that 99.7 percent of the state’s utilities are federally compliant and the state’s division of water is aware of the disinfectant byproduct issues as well.

“A lot of water companies are dealing with a different level of restrictions on disinfection byproducts,” Mura said, and added that the state has been working with companies to address these issues in recent years.

“We’re trying to limit the amount of time that the disinfectant is in contact with the organic matter, the carbon based organic matter,” Mura said. “And that really is dependent on how each operator is doing it. So there’s no one solution that fits all.”

Glass is concerned that water consumers who see the EWG information might begin to lose faith in their tap water and turn to bottled water. But bottled water, he said, isn’t subject to the same testing requirements as public utilities.

“And it’s a lot more expensive by volume, so if you are going to use bottled water for all your drinking and cooking needs you’d spend a lot of money and you still wouldn’t have even the same confidence that you can have in your public water supply,” Glass said.

Trade-offs

Bill Robertson stands by Paducah Water’s product.

“Well there’s always more we can do,” he said. “It’s just at what cost, and at some point you really reach a point of diminishing returns where it costs a whole lot of money to just make a very small incremental improvement in the water.”

Robertson said Paducah Water can supply one thousand gallons of water to a household for just $4, and that water will meet federal standards. For those who want water that’s more protective of health carbon filters and other water purifiers can reduce many contaminants.