News

Changing Course: “Tiny House” Project Tackles Big Problems In Coal Country

By: Benny Becker | Ohio Valley ReSource

Posted on:

The sound of power tools blends with teenage chatter as students clamber around, under, and over a trailer bed that they’re busy turning into a home. They’re part of a project called “Building It Forward,” which has vocational classes building tiny houses as a way of gaining practical skills and new confidence.

Just a few feet from the garage door at the back of the room, there’s a vertical rock face. It’s all coal from the ground up at least ten feet. Coal here can be a reminder of the past — of the time when this land that the school sits on was blasted flat by miners; of times when coal jobs were plentiful here in eastern Kentucky.

Back inside, students are using hammers, drills, and saws. Educators hope that this class will help them to feel invested in their education, so that one day they might be able to rebuild the economy here in these once-famous coalfields.

Big Goals

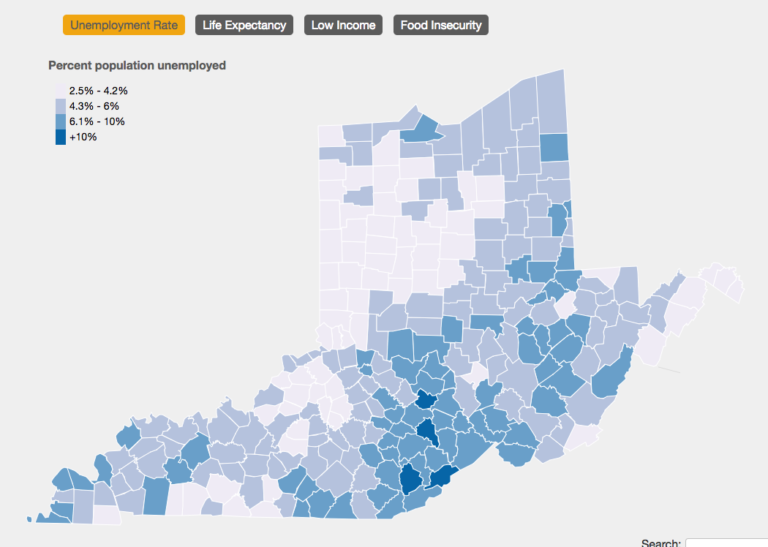

The Kentucky Valley Educational Cooperative, or KVEC, is one of eight school district cooperatives in Kentucky, and it’s the one that covers the famed eastern Kentucky coalfields. The fifth congressional district, which contains the KVEC region, has an unemployment rate roughly double the national average, and the country’s lowest life expectancy.

Three years ago, the cooperative won a $30 million federal grant to fund innovation and personalized education in classrooms throughout eastern Kentucky.

“One of the groups that may not have benefited right away was the vocational school students,” KVEC Associate Director Dessie Bowling explained.

She described the tiny house project as an effort to fix that — a way of making sure that the cooperative’s schools offer classes that are interesting and valuable to students, whether or not they plan on going to college.

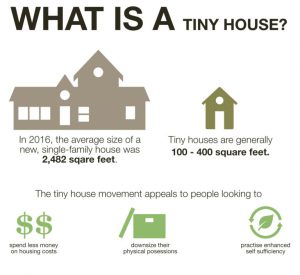

This past school year, the cooperative funded three eastern Kentucky vocational schools to design and build tiny homes. The project gives students experience with a wide range of construction skills such as plumbing, wiring, carpentry, design, budgeting, heating and cooling to name a few.

Each school received $15,000 from the cooperative’s grant. Combined with some community donations of materials, that enabled the schools to build some very thoughtfully designed and full-featured tiny houses. When the three houses were put up for an online auction, each one had multiple bidders and sold at a profit.

The program is designed to be financially self-sustaining. Money from the sales covers the costs of materials it takes to “build it forward” again the next year.

Bowling said KVEC wanted to avoid falling into the pattern of school programs that go away when funding expires. Designing the project with sustainability in mind has also modeled long-term planning for students. Bowling recalled hearing a high school senior say that he wants the program to keep going so that his children could have the chance to build a tiny home, too.

“For them to think like that, I think, is a really positive thing as well,”

Tiny Interior

Bowling showed visitors around a blue tiny house that sits in the parking lot behind KVEC’s offices in Hazard. The tiny house was built by high school students at the Knott County Area Technology Center, and bought by KVEC to serve as a model for the program.

When you walk into the house, you’re surrounded by a small but beautiful oak interior. A staircase on the left leads up to a loft that fits a queen-sized bed. To save space, the steps are narrower at the bottom, and each one has been fitted with a slightly angled drawer.

When this house was first completed and presented to a gathering of people at a KVEC summit, Knott County student Charles Collin Mosley beamed. “I took a lot of pride in those steps,” Mosley told the crowd. “They’re all custom, they’re real sturdy. I’m just really proud of it.”

Steve Richardson is a truant officer in Knott County. He said the tiny house project has made a big difference for some the students who in previous years had missed a lot of class, to the point where he’d had to make home visits.

“We’ve been able to get them involved in the learning process,” Richardson said.

Danny Vance is the the principal of Knott County’s vocational school, the Knott County Area Technology Center. He was also struck by how much time and care students put into building the tiny house.

“It’s just the best project I’ve ever been involved with,” Vance said.

Next Round

Three schools are building their second tiny house this year, and five other schools got funding from the cooperative to join the ranks. The vocational school in Letcher County is one of the sites building a tiny house for the first time.

As her classmates knocked the final floorboard into place, carpentry student Haley Hart explained the process.

“They’re just knocking it in with a piece of wood and drilling holes on the side of it,” she said. “Then they’re just going to screw it down, and that’s the floor laid.”

This is Haley Hart’s second year taking carpentry. She said she likes how much freedom students have in the class. “Most of the time in other classrooms when you have an idea, you’re not allowed to do it,” Hart said. “But in here you’re allowed to do anything that comes to your mind.”

Hart said she never would have imagined that she’d take part in building a tiny house. She said the experience has made her more confident and also given her communication skills that she expects to come in handy when she’s applying for colleges and jobs.

One of Hart’s classmates, Matthew Collier, said he thinks the tiny house project is especially important in small towns like his own, where shrinking industries have left communities struggling to imagine a new economy and a new identity.

“Everybody loves this class,” Collier said. “We do the best we can, and when we’re done, buddy, it’ll look like a million dollars.”

Eight schools in eastern Kentucky are now building tiny houses. Students have a deadline to finish construction by April, when the tiny homes will be exhibited and put up for auction to fund another round of construction.

You Can’t Outsource Housing

On the day that Dessie Bowling was showing off some of the student’s handiwork in Hazard, another of the tiny houses built by students at Phelps Area Technology Center in Pike County was being hauled away.

Charles Hawkins explained that one of his sons bought it to use as temporary housing.

“They discovered that they had a black mold,” Hawkins said. “So they’re going to get this to use until that’s finished and then they’re either going to sell this thing or take it out to the lake somewhere and park it.”

Hawkins said he not only likes the product, he supports the idea behind it.

“They need to concentrate more on vocational trades, because every kid that’s going to school’s not destined to become a lawyer or a doctor,” he said. “Somebody’s got to fix the plumbing. Somebody’s got to wire the house.”

That thinking is echoed by another of Hawkins’ sons, Jeff, who is KVEC’s executive director. Jeff Hawkins said vocational training has been an important part of the cooperative’s education strategy.

“We chose to focus on college and career ready,” he said. “And I emphasize ‘AND’.”

Hawkins said vocational skills like those students are learning in the “Building It Forward” program are integral to the “personalized learning” concept that KVEC schools have adopted.

“If you are really focused on personalized learning it needs to be connected to individual passion,” he said. “Draw a solid line between what they were doing in school and how that translates to what they would do after that.”

Scott McReynolds heads the Housing Development Alliance, based in Hazard. He said that a tiny house could be a good, affordable option for tourists, students, minimalists, and many other people.

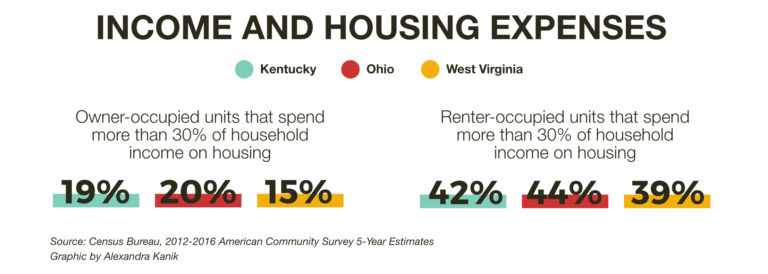

McReynolds said that eastern Kentucky has a lot of housing needs, including a large amount of rundown and substandard housing.

He pointed out that construction and home repair are kinds of work that can’t be done by people who aren’t locally available, so it’s an area where there will definitely be local needs, and jobs are less likely to go away.

“What really excites me,” McReynolds said, “is the skills that students are learning … are really translatable to the rest of the solutions we need.”

This series is supported by the Solutions Journalism Network.