News

Students Push As Lawmakers Ponder Gun Safety Bills

By: Nicole Erwin | Ohio Valley ReSource

Posted on:

In a recently released court video, Capt. Matt Hilbrecht of the Marshall County, Kentucky, Sheriff’s office testifies about his interrogation of Gabriel Parker, the 15-year-old accused of a mass shooting at Marshall County High School in January.

“We asked him initially when he had the thought of the school shooting,” Hilbrecht begins as he describes the events leading up to the shooting. The recording was released because Parker is being tried as an adult.

Hilbrecht explains how Parker got the 9mm pistol he would use to kill two teens and injure 17 others: Parker found it in his parents’ closet.

“As he went into the bedroom he retrieved a pistol that was still in the case from the closet and stuffed it in between the clothes to conceal it,” Hilbrecht relays in the video. “Then he actually left it in the laundry basket till that morning of the shooting.”

The testimony confirms earlier reports by the ReSource that the gun came from the home. It’s a sadly common occurrence.

A 2004 study from the U.S. Department of Education and Secret Service, and a 2015 report from the nonprofit group Everytown for Gun Safety both found that the majority of school shootings by students involved guns obtained from the home or family members.

Six weeks after the school shooting that shocked this small community, state legislators in Kentucky and elsewhere around the Ohio Valley are again considering legislation that would require secure storage of firearms around minors. But some students newly energized to lobby for school safety are losing patience.

“Talking”

“We are talking about it. It is not dead,” Kentucky Republican State Sen. Whitney Westerfield said of Senate Bill 184. Westerfield chairs the Judiciary Committee where the bill was sent after introduction by Democratic Sen. Gerald Neal. Westerfield has the ability to move the bill out of committee and to the floor for a vote.

“I appreciate the effort of the bill,” Westerfield said. “While I am a staunch supporter of the Second Amendment, I think it is worth looking at whether or not handling them improperly or unsecurely, I think that is something we should look at, I think that’s something we should consider.”

The bill makes improper storage of firearms in homes with a minor a misdemeanor offense. Westerfield said Neal’s bill needs work to more clearly define safe storage before it can move forward. Two other child access prevention bills are stalled in a House committee.

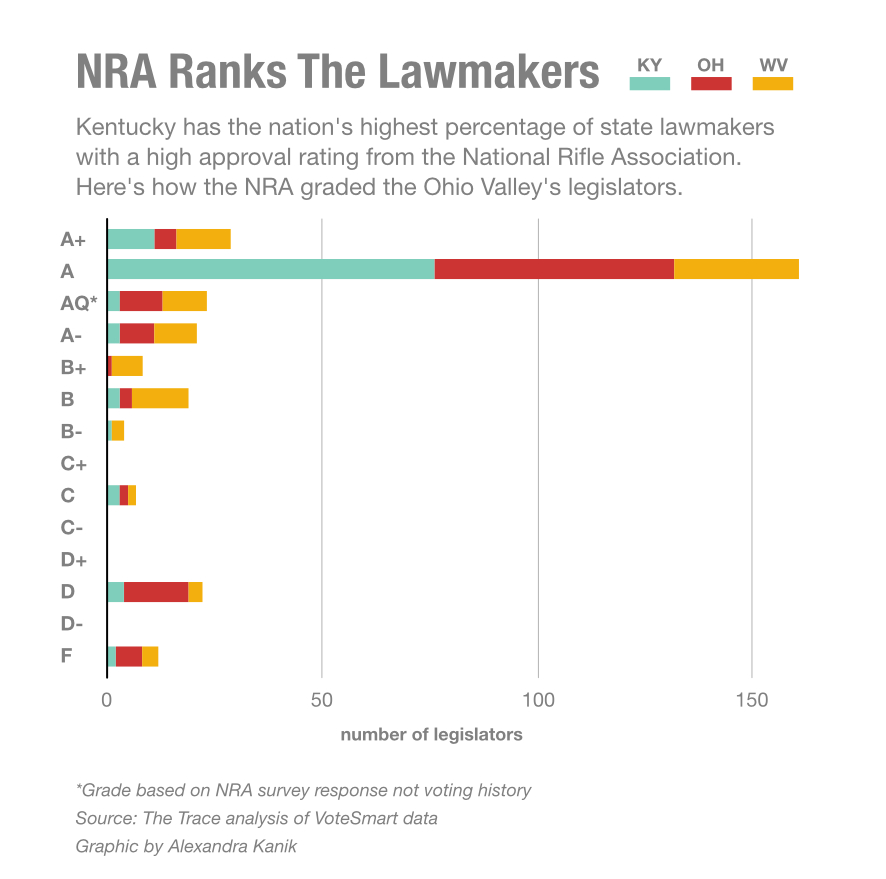

Westerfield boasts an “A” rating from the National Rifle Association, as do most Kentucky state legislators. An analysis of the NRA’s recent lawmaker ratings conducted by The Trace, a journalism nonprofit covering gun violence, shows Kentucky has the nation’s highest percentage of legislators who got at least an A-minus grade from the NRA, 88 percent.

In Ohio, 67 percent of lawmakers got As; In West Virginia, about 60 percent.

Similar child access prevention legislation in Ohio sponsored by Democratic State Rep. Bill Patmon is also stalled in a committee. Patmon has tried and failed to pass the bill for several years now.

Other Gun Bills

Other gun-related bills in the Ohio Valley region are moving forward, but those advancing tend to expand where guns can be carried.

“Unfortunately, we’ve also seen a dangerous policy response to the school shootings. And that’s a proposal to arm teachers and school staff,” said Hannah Shearer, a staff attorney at the Giffords Law Center to Prevent Gun Violence, which formed after Arizona U.S. Rep. Gabby Giffords was shot in 2011. “Those bills are dangerous.”

Shearer said West Virginia has passed legislation that would expand where people could carry firearms, including some private school grounds and public school functions. Ohio is moving in a similar direction with a bill to allow more latitude for people who have permits to carry concealed weapons.

“It would decriminalize carrying a firearm in a school safety zone as well as in a bar or a courthouse by people with a concealed carry permit,” she said.

Student Response

In the wake of the January bloodshed in Marshall County and February’s carnage in Parkland, Florida, March has become a month of activism for many students. Student activists such as 17- year-old Madison Betts of Calloway County High School, located just a 30-minute drive from Marshall County High, are responding to the violence by organizing, lobbying and demonstrating for safer schools. But Betts said she feels that legislators are not listening.

“We can go to the capitol and we can advocate and we can speak and we can protest, but they’re not taking us seriously,” she said. “So now we’re doing walkouts.”

She’s participating in a brief student walkout: 17 minutes to reflect on the 17 lives lost during the Parkland, Florida, shooting. Betts said she’s willing to risk possible discipline for missing class.

“I thought, you know, ‘What if I do this and then I’m not allowed to walk at graduation?’” she said. “But then I think, you know, ‘What if I don’t do this, and then other kids don’t get to walk at their graduations because they don’t make it.”