News

Orphan Wells: States Wrestle With Soaring Costs For Oil & Gas Industry Mess

By: Brittany Patterson | Ohio Valley ReSource

Posted on:

William Suan is no stranger to the problems abandoned oil and gas wells can cause.

“It’s just an eyesore,” he said, standing inside a barn on his cattle ranch near Lost Creek, West Virginia. “I had to fence one off because it’s leaking now.”

There are five inactive wells on his land, most installed in the ’60s and ’70s, and the companies that owned the wells have long since gone out of business.

On a recent rainy Monday, Suan treks down a muddy hill on the backside of his property. Hidden in the wooded thicket is a three-foot-tall rusted tube jutting out of the ground.

A soft bubbling sound emanates from the well.

“See the gas bubbling out of it?” he said. “Sometimes there’s oil. There’s where they had one of those pads to soak up the oil last time I complained about it.”

In 2012, Suan won a case against the West Virginia of Environmental Protection to get one of the wells on his property plugged. Since then, he says he has been unsuccessful in getting environmental regulators to take additional action.

Having enough resources to plug old, inactive wells is a challenge not unique to West Virginia. Across the country, many state regulators have few resources to deal with an ever expanding list of abandoned wells.

“The states are pretty good at regulating wells that are being explored, are being fracked, are in production, but they kind of lose interest once that happens,” said Alan Krupnick, a senior fellow with the nonpartisan environmental think tank, Resources For the Future. “There’s not enough attention being paid to reducing the risk from these abandoned wells.”

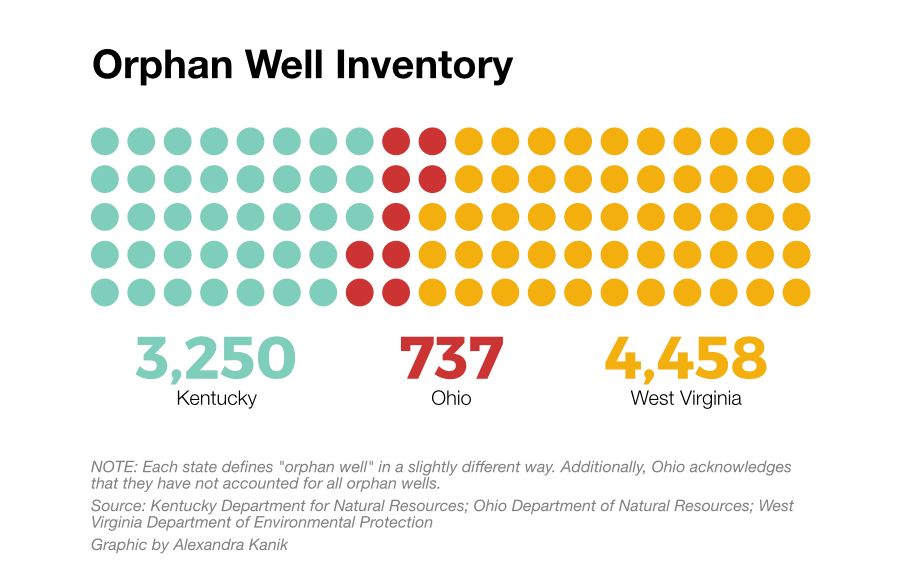

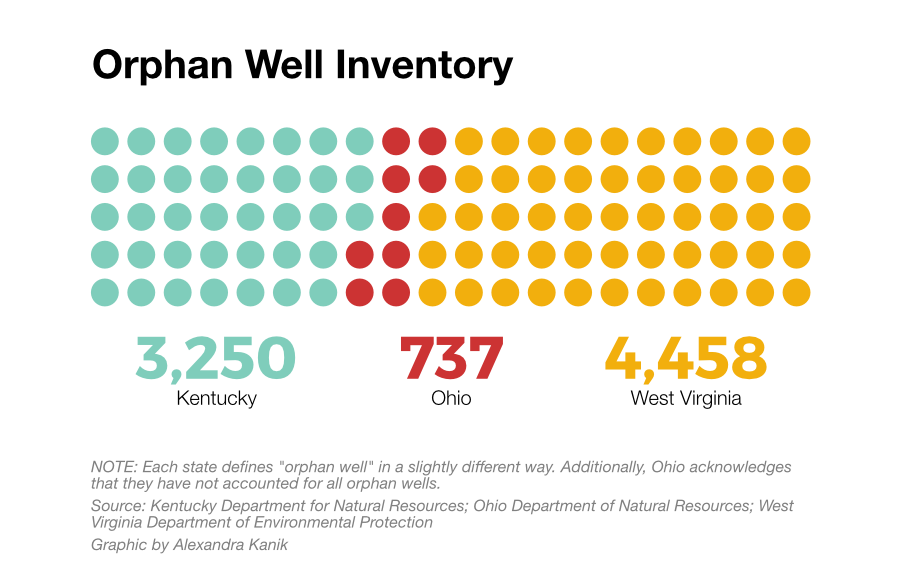

Across the Ohio Valley, thousands of oil and gas wells sit idle. An analysis of state data by the Ohio Valley ReSource estimates more than 8,000 oil and gas wells are considered “orphan.” Definitions of orphan and abandoned wells vary by state, but in general, orphan wells lack an operator or company that can pay to plug them. That responsibility then falls to state regulators who are frequently struggling to keep up with demand and scrambling to find money to clean up the mess.

But there are steps states can take to help. Recent legislation passed in Ohio and West Virginia funnels more money toward plugging orphan wells. The new laws address the problem in two very different ways.

Inadequate Bonds

In Kentucky and West Virginia, agencies tasked with plugging those wells rely on forfeited bonds. That money is collected in a fund and used to plug the highest priority wells.

Well plugging can be an expensive undertaking. Across the Ohio Valley, regulators reported figures as low as a few thousand to upwards of $200,000 to plug a single well.

“We may have an emergency repair on a big well and we may have had bonds forfeited on several small wells and those funds just don’t add up,” said Lanny Brannock, a spokesperson with the Kentucky Energy and Environment Cabinet. “So, we’re constantly behind on funding for orphan wells.”

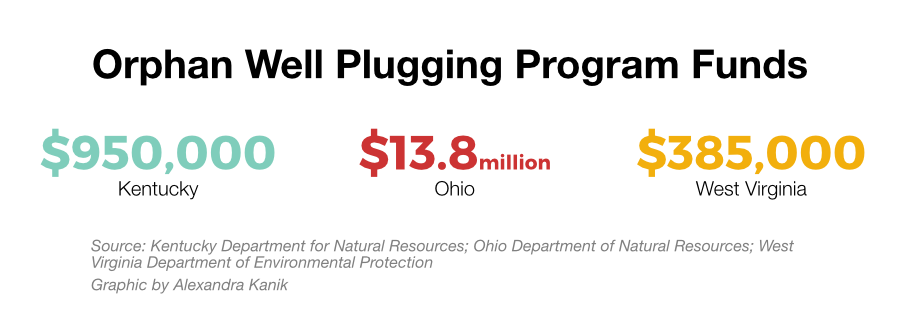

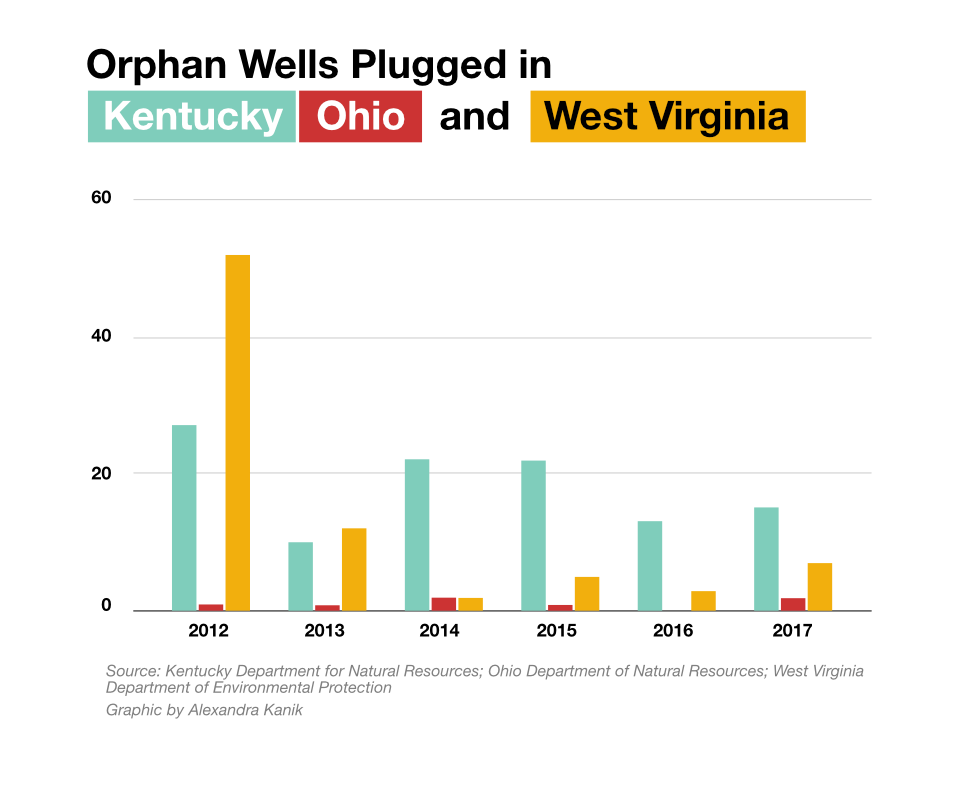

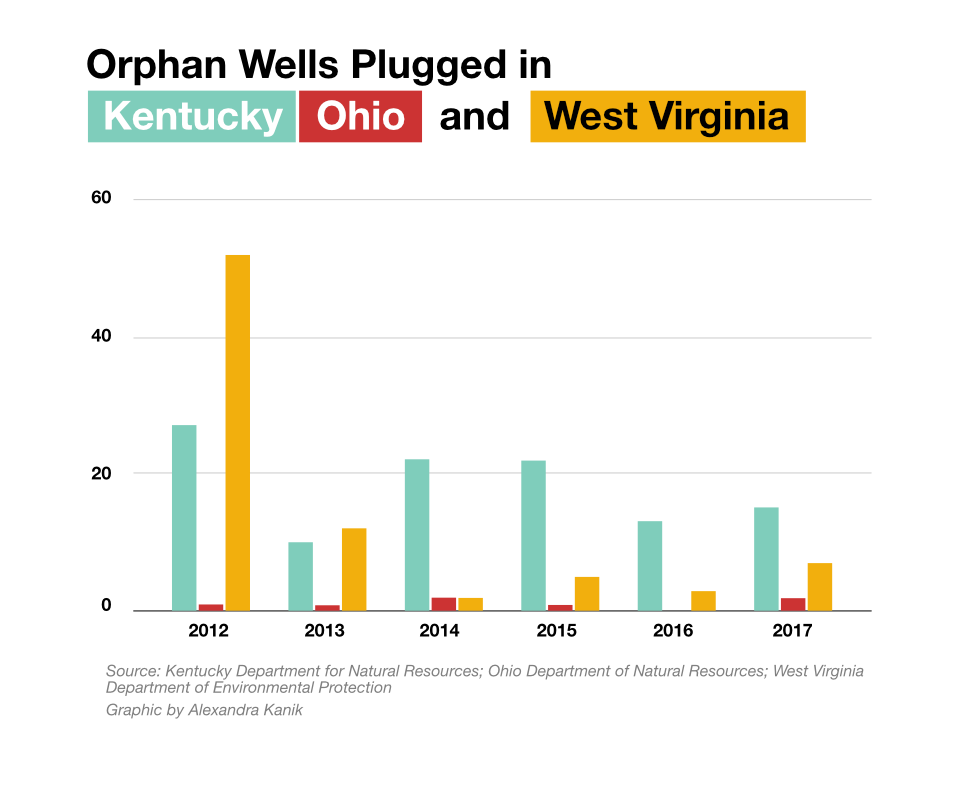

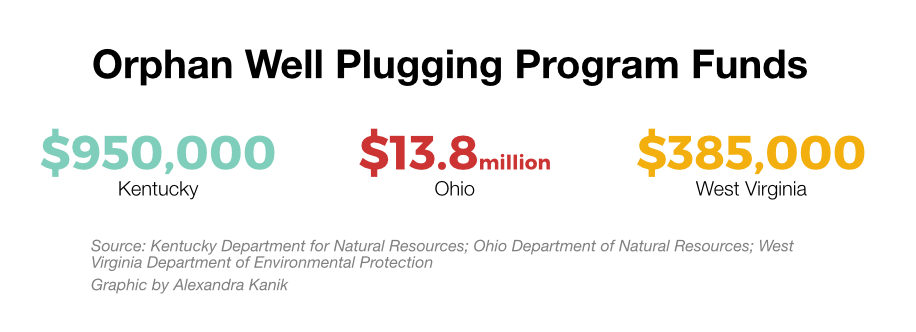

Since 2012, Kentucky has plugged 33 wells and has about $950,000 in an orphan well fund.

West Virginia’s funding situation is similar. Since 2012, the state has plugged seven wells. The West Virginia Department of Environmental Protection can use a portion of each $150 well work permit application fee as well as any forfeited bonds to plug orphan wells. Currently, the fund holds approximately $385,000.

Recent legislation passed in Ohio and West Virginia funnels more money toward orphan wells. The new laws address the problem in two very different ways.

WV Fix

In West Virginia, the 2018 “co-tenancy” law, which governs oil and drilling on properties owned by multiple people, includes a provision with the potential to funnel millions of dollars into the state’s orphan well fund.

The law states that if at least 75 percent of landowners agree to lease a tract of land for oil and drilling, a company can drill. Any royalties earned by mineral owners who cannot be located will be set aside for 7 years. If unclaimed, those funds are transferred to the orphan well fund.

“We’ve been looking for years for a way to find the money or require the industry to pay better bonds in order get these wells plugged and keep more wells from being orphaned,” said Dave McMahon, a lawyer and co-founder of the West Virginia Surface Owners Rights Organization, which proposed the idea to lawmakers.

A portion of the money is currently slated to fund West Virginia’s struggling Public Employee Insurance Agency, or PEIA.

“Hopefully, we can use this source of money as one way to try and plug as many of these orphan wells as we can,” McMahon said, but added, “It’s hard to know if we’ll ever get the job done because there are so many of them and there are going to be so many more of them and it costs so much to plug them.”

The West Virginia Department of Environmental Protection declined to make someone available to talk about its orphan well program.

In an email, spokesperson Jake Glance said, “Our understanding is that certain provisions in the co-tenancy bill will eventually direct additional funds into this account.”

While the new legislative fix is helpful, experts say the orphan problem will only get worse because West Virginia and other states do not require drillers to pay adequate bonds.

Deep Problems

A 2016 study of inactive well regulations in 22 states by Resources for the Future, a nonprofit advocacy group, found the majority lack policies to deal with legacy wells drilled decades ago and the means to collect sufficient funds to plug wells currently being drilled.

“We want good policy to make sure that these wells when they’re eventually abandoned do not present environmental risk” Krupnick said. “One thing is they could raise the bonding amounts to the point where they’re covering the costs of these wells, of decommissioning the wells.”

He said another challenge is that many states allow wells to remain in “idle status” for years. These wells aren’t producing, but operators aren’t being required to plug them.

Unplugged wells can leak oil and other pollutants into water or the ground and inactive wells can emit methane, a powerful greenhouse gas many times more potent than carbon dioxide.

A 2016 study of abandoned wells in Pennsylvania found the state’s 475,000 to 700,000 abandoned wells are leaking an estimated 50,000 metric tons of methane per year, or about 5 to 8 percent of the state’s annual greenhouse gas emissions.

Experts say the problem will only get worse. The region’s fracking boom is adding many more wells that tap the gas deep in the Marcellus shale. The lifespan of a fracking well is shorter than a conventional well. According to McMahon, pressure from Marcellus drilling is also likely to force some conventional drillers out of business.

“Their bonds aren’t going to be enough and the number of orphan wells is going to go up and up as time goes on,” he said.

In 2011, West Virginia overhauled its bonding requirements for horizontal wells. The 2011 Horizontal Well Act requires drillers to pay $50,000 for single well bonds and $250,000 for blanket bonds.

Companies in good standing can get blanket bonds to cover all wells they own. McMahon argues that even that level of bonding may not be enough to prevent orphan wells.

“That blanket bond is enough to plug five wells and some of these drillers own hundreds of wells,” he said.

Ohio’s Approach

On a forested knoll in Carroll County, Ohio, backhoes and bobcats zip around. Nearby, a crew of three men is running 2-inch metal pipe hundreds of feet down into an old well that was built before World War II.

Gene Chini manages the orphan well program for the Ohio Department of Natural Resources division of oil and gas resources. The wells being plugged here have been on the agency’s radar for awhile.

“The records that we had said this well was the best in Carroll County,” he said

Ohio has taken a different approach to plugging orphan wells. In 1977, the state created an orphan well plugging program. From the beginning it has been funded with 14 percent of the oil and gas fund, which is supported by a modest severance tax on natural gas extraction.

Later this month, a new law will raise the percentage of the fund that must be directed toward orphan wells to 30 percent.

Soon, the Ohio Department of Natural Resources Division of Oil and Gas Resources hopes to be plugging many more wells.

Brittany Patterson | Ohio Valley ReSource

Brittany Patterson | Ohio Valley ReSourceGene Chini says there may be thousands of abandoned wells in his state.

“Four to five years ago the budget was less than a million dollars,” said Steve Irwin, spokesperson for the division. “This past fiscal year we spent $6 million and we will have over $20 million to spend this year to plug orphan wells.”

In addition to the percentage boost, severance taxes are up significantly because of the fracking boom in Ohio.

The division is facing some challenges ramping up the program. There are just 737 orphan wells on the agency’s list, but officials said an estimated 250,000 wells have been drilled in Ohio. They expect the true count of orphan wells to be much higher.

It can also be a time-intensive process to plug old wells. In the case of the five wells being plugged in Carroll County, Chini said none had gone according to plan.

“It’s not just pull in, pump some stuff down a hole and then leave, it just doesn’t work that way,” he said.

The standard way of plugging a well involves first clearing out all of the tubing and casing inside. Then cement or another strong substance is poured in to create a combination of deep and shallow plugs to ensure oil and gas cannot escape or travel into the groundwater.

The state is also struggling to find companies to plug wells. Chini said when conventional oil and gas business dropped off in the 1990s, many companies left Ohio.

Still, he recognizes with a boost in funding tied to severance taxes, Ohio is in a better place than some.

“It really is a win win for everybody,” he said. “The money’s coming back to them in the form of work. It’s the operators that pay the severance tax and so it’s the operators that are plugging the wells.”

On The Horizon

Back in West Virginia, Suan said he was glad to hear about the new provision that puts more money toward plugging orphan wells. But he fears without higher bond amounts, or enforcing the laws to make oil and gas operators plug wells in a timely manner, the problem may never go away.

The region’s fracking boom is adding many more wells that tap the gas deep in the Marcellus shale.

“I can’t imagine if they can’t even plug these little wells what they’re going to do with the Marcellus wells that needs plugging,” he said.