Finding Faith—Somewhere Else

By: Rachael Beardsley

Posted on:

March Washelesky no longer believes in a God.

Rather than follow the teachings of the church, Washelesky has chosen to separate themselves from the Catholicism of their childhood. And they are far from the only ones.

A 2014 study by Pew Research Center found that 23 percent of Americans have no religious affiliation. Though their numbers are small in comparison to the 71 percent of Americans who identify as Christian, the population of “nones” continues to rise. A January 2018 study estimated that around 26 percent of American adults now identify as atheist.

These numbers ask a complicated question of the religious community: Why are people moving away from faith? The most common reason, Pew found, was simple questioning of religious teachings. The second most common reason was opposition to the church’s social and political stance, including teachings on homosexuality.

As a result, LGBT people of faith and their allies are faced with a unique challenge. How does one retain belief in the divine despite the harsh rhetoric that sometimes accompanies religious teachings? For some, balance was within reach. Others have found different paths.

Leaving the Church

“I remember when I was really young, I was very defensive about being Catholic to the point where people would express doubts or something like that, and I would be aggressive toward it,” said Washelesky, a 19-year-old college student who identifies as nonbinary and uses gender-neutral pronouns.

Though Washelesky’s family is not Catholic, they attended a Catholic grade school and followed the teachings of the church. But by the time they entered the eighth grade, they were experiencing doubt about their beliefs. So, they chose to keep religion at a distance for the next few months, even though they were concerned about the reaction from those around them.

“I expected more of a push-back from [my teachers],” they said. “But they were just sort of like okay, I mean you still have to go to church with us, but you [don’t have to] stand up and get communion if you don’t want to.”

Eventually, Washelesky decided a religious path was not right for them.

“It wasn’t necessarily a decision at the time that I don’t want to be religious, it was I’m not sure enough to be confirmed,” they said. “I just felt like it was really weird that all of my friends knew when they were 13 that they wanted to do that for the rest of their lives.”

They added that their queer identity may have been a subconscious reason they chose to leave religion, although it was not on their mind at the time.

“I had no conscious idea that I was queer until at least sophomore year [of high school], and I wasn’t out about it until significantly later,” they said.

In their opinion, organized religions are not moving fast enough for modern values.

“More things in the culture [are] open to queer things and, to a lot of people, incompatible with their religion, although that’s kind of changing,” they said. “I think a lot of attitudes are being challenged, and that the organized religions aren’t moving quickly enough to change with it to continue getting people to stay with them.”

Today, they do not hold themselves to any specific label. Instead, they look at religion from a personal viewpoint.

“I don’t know that there’s a word for this, but I don’t care if there is a God because if there is a God, I wouldn’t worship them,” Washelesky said. “I do think now that there is a kind of comfort [in religion]. Not having that is rough. Like, I wish I did believe in a God, but I don’t.”

One Church’s Perspective

Though the common idea is that religion and the LGBT community do not mix, there are actually many religious organizations trying to bridge the gap between the two groups.

One such organization, Believe Out Loud, is an online Christian LGBT advocacy group formed in 2009. The group advocates for both religious and political justice for the LGBT community. One of their practices is rating different denominations on their levels of LGBT affirmation. The Episcopal Church, for example, has been rated as having overall affirming LGBT policies and practices, while the Roman Catholic Church has been given an overall rating of discriminatory.

Many other churches fall somewhere in the middle. The United Methodist Church is rated as making progress toward LGBT acceptance at the local level, although the official church policies are still discriminatory and hold that “the practice of homosexuality is incompatible with Christian teaching.” However, many individual United Methodist churches have begun to promote LGBT-inclusive policy.

At Athens First United Methodist Church in Athens, Ohio, senior pastor Robert McDowell attributes the shrinking number of religious people in America, in part, to the loud voices of certain Christians who may not necessarily speak for the whole faith.

“[Another reason may be] religious people who have behaved badly and maybe not earned the right to speak about their faith because they have been hypocrites, and people see that, and they see through it,” he said.

McDowell says he tries to lead his church in an open and authentic way, and to welcome whoever might come through the door.

A Middle Ground

delfin bautista, the director of the LGBT Center at Ohio University, champions acceptance and tolerance on the university’s campus. bautista works with the university and surrounding community in creating a more inclusive environment welcoming of all identities and orientations. What many people are unaware of, however, is that they also hold a master’s in divinity and have a background as a chaplain.

“I was raised as a Catholic in a very conservative home where there was no space for questioning,” said bautista, who uses gender neutral-pronouns and the lowercase spelling of their name. “I think when things started to change was when I did come out in my 20s and started to ask questions and recognizing that asking questions did not make me any less of a Catholic or a Christian.”

After leaving seminary school, bautista found work as a hospital chaplain. That work, they said, set the stage for their current job at the LGBT Center, where they create a safe space for students and community members to share their stories.

When students come in struggling to find a middle ground between an LGBT identity and a religious identity, bautista says they are able to speak with the students from a place of similar, though not identical, experience.

“Having a religious background doesn’t help me understand, however it does give me a starting point for relating to what their going through,” they said. “Many people don’t realize there is a pro-LGBT religious movement. A lot of folks come and leave just very surprised that there is an inclusive movement, and a very vibrant movement, across religious traditions. It’s been humbling and exciting to introduce folks to a different side of religion that doesn’t get talked about much.”

bautista added that, for many religious LGBT people, questioning their faith is a natural part of the healing process.

“It’s okay to ask questions, and its okay to wrestle with this stuff,” they said. “For some folks, it means staying within a tradition. For some folks, it means leaving that tradition and joining another tradition, and for other folks, it’s just leaving religion altogether, but doing so from a place of empowerment where they no longer feel shame.”

An Alternative Path

Though not given quite as much attention as traditional religious paths, alternative and New Age religions such as neo-paganism can often offer a striking difference to the intolerance many people perceive in mainstream religion.

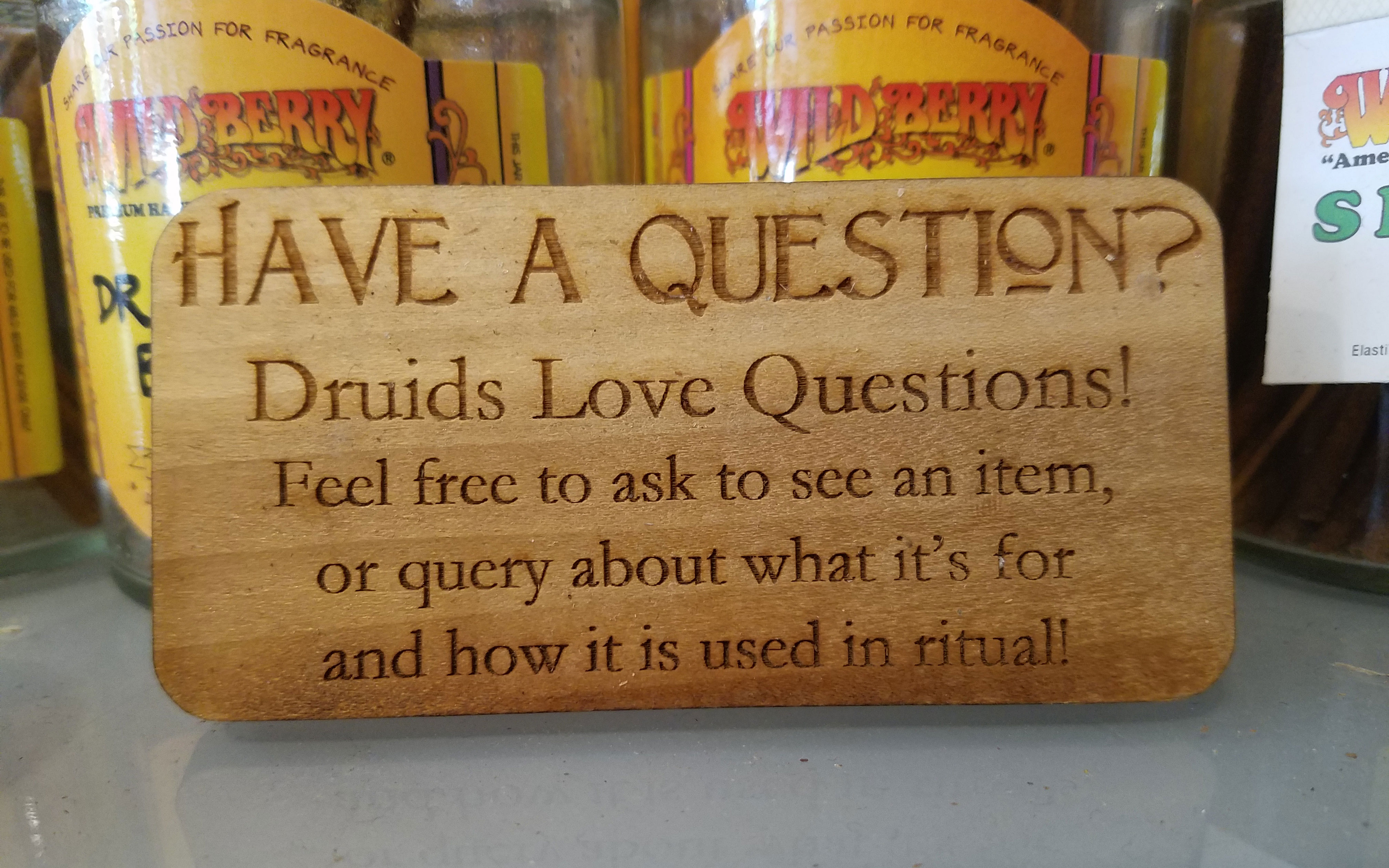

“I suppose the thing that really drew me to it was the nature-based aspect,” said Michael Dangler, co-owner of The Magical Druid Spiritual Resource Center and Modern Apothecary in Columbus, Ohio. “I like the idea that our cosmos is something that is broader than what we would typically understand, and that we can have a positive effect on it.”

Dangler is a practicing Druid and Grove Priest at Three Cranes Grove, A Druid Fellowship, an organization in Columbus. The group holds many public rituals in an effort to share their faith. They also have an anti-discrimination policy that forbids exclusion of anyone based on sexual orientation and bans homophobia and other forms of discrimination during their events. Their level of tolerance is not uncommon in neo-paganism.

The different branches of neo-paganism can vary greatly, but almost all contain reverence for nature and the practice of rituals. Beyond that, there are not many strict requirements for following the tradition. Practitioners are able to choose what best fits their own worldview.

“There’s a whole bunch of afterlife notions out there, and none of them are necessarily correct or right, and in a lot of ways it doesn’t necessarily matter what a person believes,” Dangler said. “What is important is honoring the ancestors, and a memory of what it is that the ancestors mean to us, and passing on those stories.”

When Dangler sees the trend of people moving away from religion, he is not surprised. He agrees with Washelesky in saying that religion has not been quick to catch up with modern thought.

“This is weird, probably, coming from a pagan who looks to old religions for inspiration, but I think a lot of religions just have a tough time updating themselves and reflecting the people who are a part of the body of that religion,” he said. “And that is not unique to any particular religion. It’s the way all religions are when they become more and more organized.”

The Value of Questioning

With the number of non-religious Americans rising, it’s worth asking what the overall value of religion is in today’s world. Surprisingly, Washelesky, bautista, McDowell and Dangler can all agree on one thing: Questions are welcome, and so is uncertainty.

For Washelesky, questioning came in the form of distancing themselves from and ultimately leaving the Catholic Church. For bautista, questions were and still are an integral part of putting together the puzzle pieces of multiple identities.

“Folks such as myself and hundreds and thousands of people around the world [are] asking questions … as a form of liberation because many of us were raised in traditions where we were told you cannot,” they said. “The fact that … we’re going to do this on our terms now … is really exciting.”

McDowell, for his part, welcomes questions and authentic conversation, while Dangler embraces questioning through a faith that is relaxed and open.

Dangler says it’s possible that people aren’t heading toward a total lack of spirituality, though the statistics may paint it that way. Instead, he says, people might be searching for new ways to find meaning, whatever form that may take.

“I don’t think that people are necessarily leaving religions so much as they are finding new paths to make those connections,” Dangler said. “Whether that is doing something completely different, like showing up to a pagan ritual, or whether it is doing something that’s not all that different, such as moving from one evangelical group to another, it’s all about digging for that connection.”