Culture

‘But How Could He Be Forgotten?’ Looking Back on Æthelred Eldridge

By: Emily Votaw

Posted on:

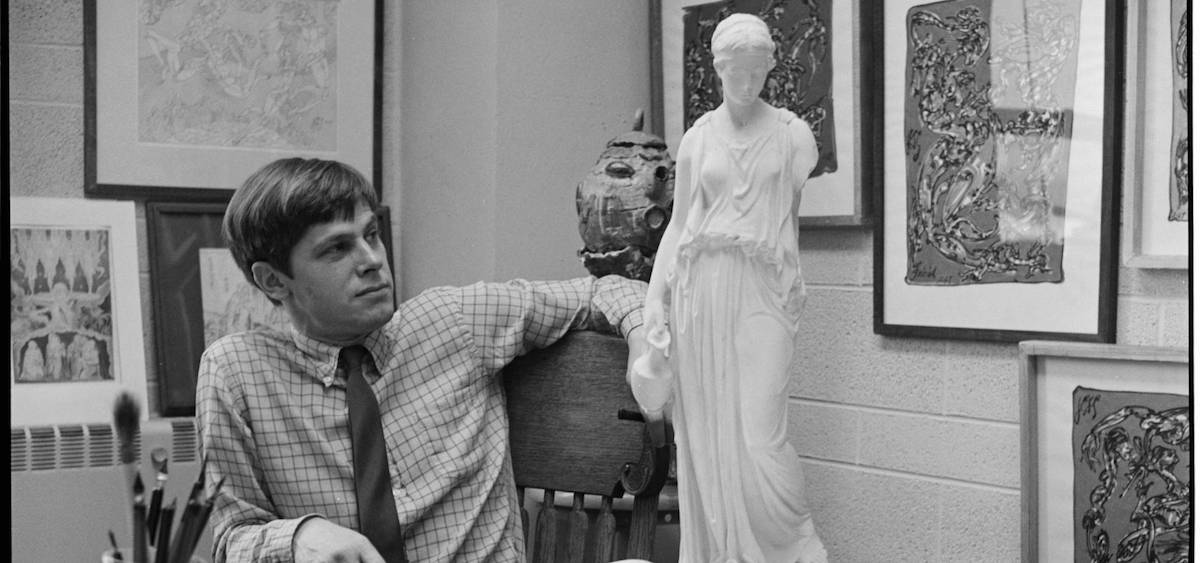

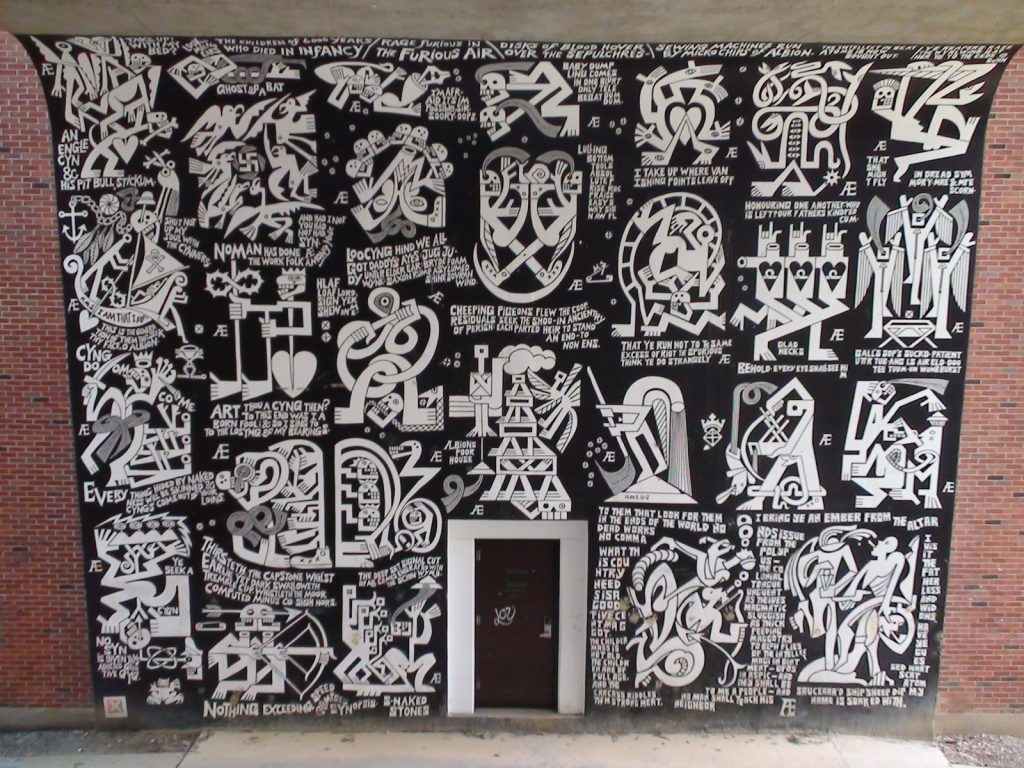

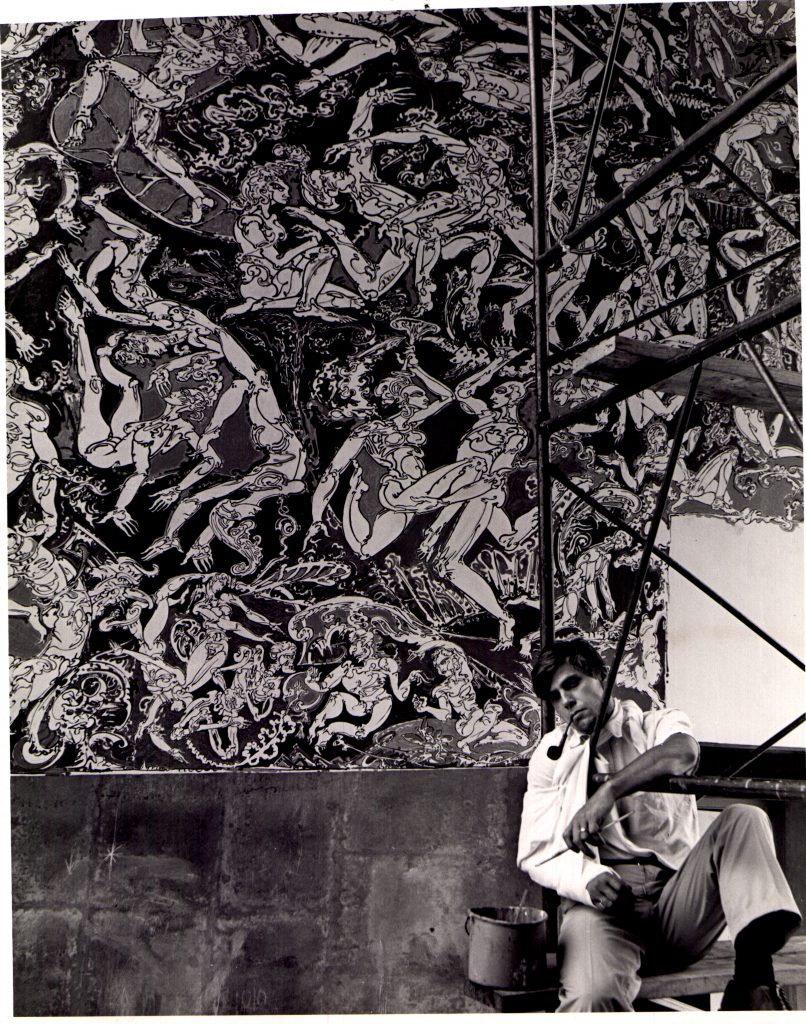

On Monday, November 12, 2018, James Edward Leonard Eldridge, known primarily by his chosen name, Æthelred Eldridge, passed away at the age of 88. He was an associate professor of painting at Ohio University’s School of Art and Design from 1958-2014. He is also one of the select few artists listed in the Dictionary of the Avant-Gardes by art critic Richard Kostelanetz. His work, which tended towards the esoteric, might be known most specifically in a regional sense by his 50-by-80-foot mural in the amphitheater of Siegfred Hall on Ohio University’s campus.

“(Eldridge encouraged) this notion of understanding what a thing is on its own terms,” Duane McDiarmid said. McDiarmid is the Area Chair and Professor of Sculpture and Expanded Practice at Ohio University’s School of Art + Design. “As a human animal, our notion of what is a place is tied to maps and geography and words and names and titles and political structures – and that’s all true, but before those things, as human beings, there is another experience we all have that makes us one with one another. When we are in the dark, on some level we are afraid, and we are in need, so we begin with something. This is the sort of thing Æthelred would take people through.”

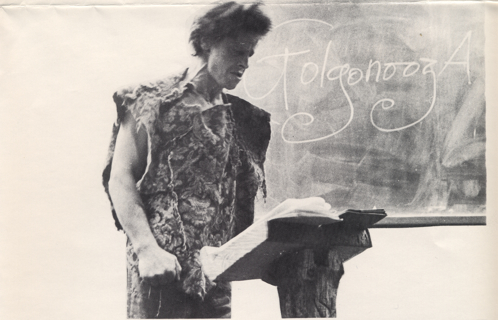

McDiarmid is one of many of Eldridge’s students, colleagues, and friends who expressed that they were permanently changed by what several sources have described as the artist’s lifelong dedication to the championing of the outcast and the encouragement of the iconoclast. McDiarmid said Eldridge’s lecture classes were famously winding and poetic, often anchored in free association, philosophy, iconography, art history, and performance.

“(Eldridge) would draw a character on the board – a figure in a boat stepping off into new land – very simple and not proportionally correct, although he had the skills, he could draw like Michelangelo, he didn’t need that – what his point was is that whenever you’re stepping from the boat of discovery to the new land, you’re always in a precarious position because you’re standing up in a boat on one foot,” McDiarmid said. “There is a profound truth in that simple drawing that we all understand – that when you are (moving) from your crafted journey to new discovery, there is an amount of precariousness. These are the kinds of things that Æthelred was very interested in.”

“A lot of people thought that he was crazy or that he was just saying gibberish at the front of the class – but really his classes were him at the front of the stage in the Siegfred auditorium just speaking a stream of consciousness, connecting things, referencing things from the past and philosophies,” said Emily Beveridge, executive director of Arts West and one of Eldridge’s students in the early 2000s. “I would always sit at the front of the class to be as close to him as possible, because if you tried you could really make a connection and glean essentially what was the topic of his sermon.”

Beveridge said her initial exposure to Eldridge’s massive Siegfred mural during a tour of the campus was what sealed the deal on her choosing Ohio University as the college she would attend, and ultimately Athens as the place she would spend the entirety of her young adult life. Beveridge would go on to marry her husband, Michael Bart, underneath the mural, in 2006.

Beveridge is by no means the only student of Eldridge’s profoundly touched by the artists’ work. Athens’ Poet Laureate, Kari Gunter-Seymour, described her exposure to Eldridge as being deeply formative during a transformative portion of her life.

“I have to explain that at the time, I was a newly divorced, single mother who had just stumbled out of a holler in Meigs County and who was newly enrolled at Ohio University — and who was feeling very overwhelmed and out of place, when I stumbled upon Professor Eldridge’s class,” Gunter-Seymour said.

The poet recalled one of the assignments that Eldridge gave his lecture class was to bring in a loaf of white bread and to shape it into a “human form.”

“People used all types of methods to hold things together, I used chopsticks to hold things together, to make like arms and legs – I took it pretty literally,” she said. “(Eldridge) provided us with a dowel rod we could attach our final sculptures to, and then he told us to take them home and bring them back at the end of quarter. As you can imagine, by the end of the quarter our bread sculptures were moldy, amazing, gory, fantastically thingy things.”

Eldridge then had the students place their sculptures outside of Siegfred Hall in the grassy area adjacent to the building, as Gunter-Seymour describes it, “for all to walk by and see and enjoy.”

“In doing this, he not only taught us about the dangers of white bread – which I love, but he also showed us that sculpture is sculpture regardless of form, and that life is so fleeting, why take it seriously?” Gunter-Seymour said. “We’re all going to end up decaying in a field somewhere – that’s the way I took it, and it was a huge life lesson for those of us who were looking for it. (…) Even doubters will admit that he was a powerful force for championing otherness, for believing that it is okay to be something other than normal.”

“He (Eldridge) would draw a character on the board – a figure in a boat stepping off into new land – very simple and not proportionally correct, although he had the skills, he could draw like Michelangelo, he didn’t need that – what his point was is that whenever you’re stepping from the boat of discovery to the new land, you’re always in a precarious position because you’re standing up in a boat on one foot. There is a profound truth in that simple drawing that we all understand – that when you are (moving) from your crafted journey to new discovery, there is an amount of precariousness. These are the kinds of things that Æthelred was very interested in.” – Duane McDiarmid, Area Chair and Professor of Sculpture and Expanded Practice at Ohio University’s School of Art + Design

John Kortlander, a professor at the Columbus College of Art and Design, is a former student of Eldridge’s. His father, Dr. William Kortlander, was a professor of art at Ohio University at the same time that Eldridge was. Kortlander recalls knowing Eldridge nearly all of his life.

“From 1967 to 1968 Athens went from guys wearing khakis and crew cuts to everybody looking like Jesus. The world changed. Every faculty member — at least in the art and English departments — took off their tweed jackets and put on their blue jean jackets and went from short hair to longer hair. Everybody changed,” Kortlander said. “Æthelred really took the change to heart and really, really evolved, and the freedom of that time allowed him to become the true free thinker, free association artist that he came to be.”

Kortlander and his friend, John Douglas, created a documentary about Ethelred years ago. At the time Kortlander was experimenting with film, and Eldridge seemed like a particularly interesting subject for the media.

“(The documentary) was a biography type of thing, where we filmed him teaching, and teaching and performance were intertwined for him, and then we went out and saw his property,” said Kortlander, referencing the compound that Eldridge established with a series of log cabins and other structures near Mt. Nebo outside of Athens later in his life, near the allegedly powerful spiritual grounds of the former mid-1800s Jonathan Koons Spirit Room. The property was the location of what he called Golgonooza and the Church and School of William Blake; Blake being the esoteric poet who heavily impacted Eldridge’s work. “His property was his ongoing artwork. He was really in touch with the Earth and with the land. Eldridge was a builder and a performer, and all of these things coexisted for him.”

Karla Eldridge is one of Eldridge’s children from his first of three marriages. She distinctly remembers the safe haven that Morris Avenue, where Eldridge’s family lived early in the professor’s Ohio University career, was to her as a child.

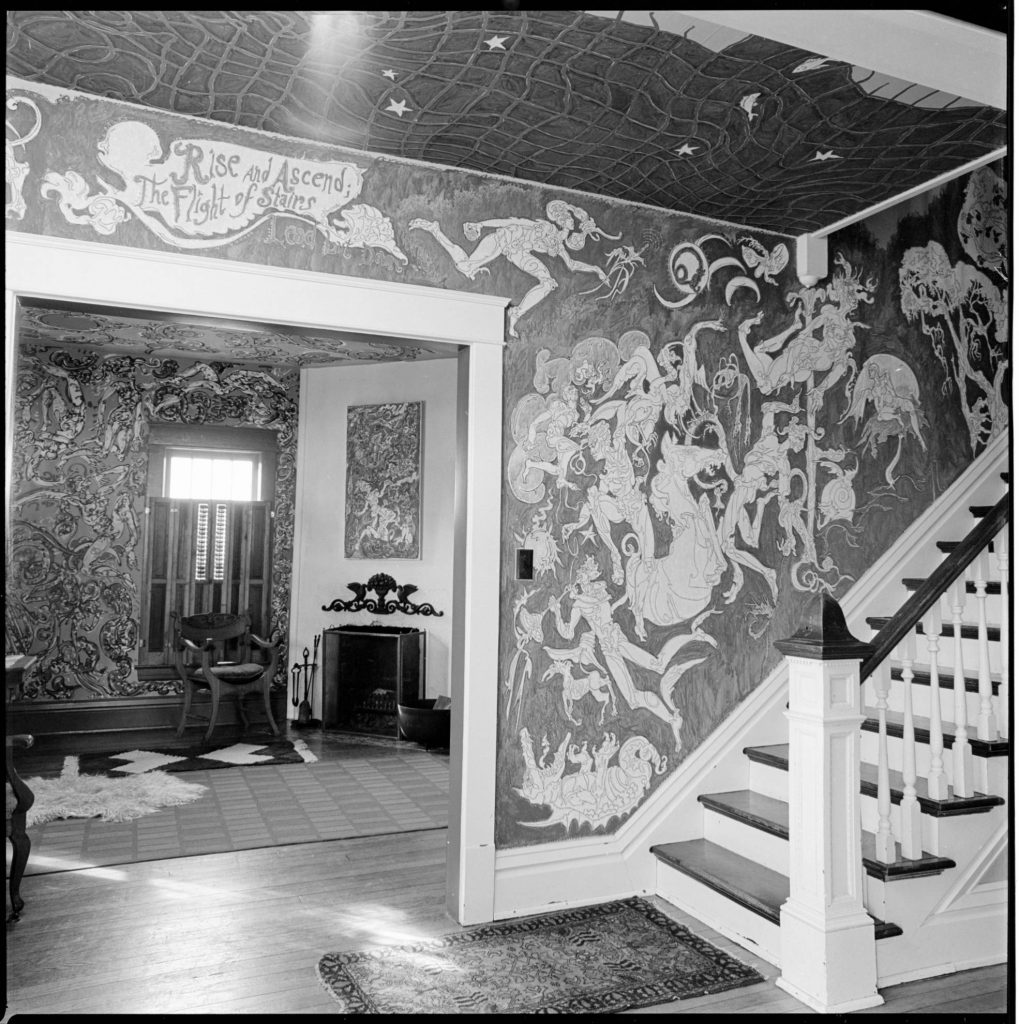

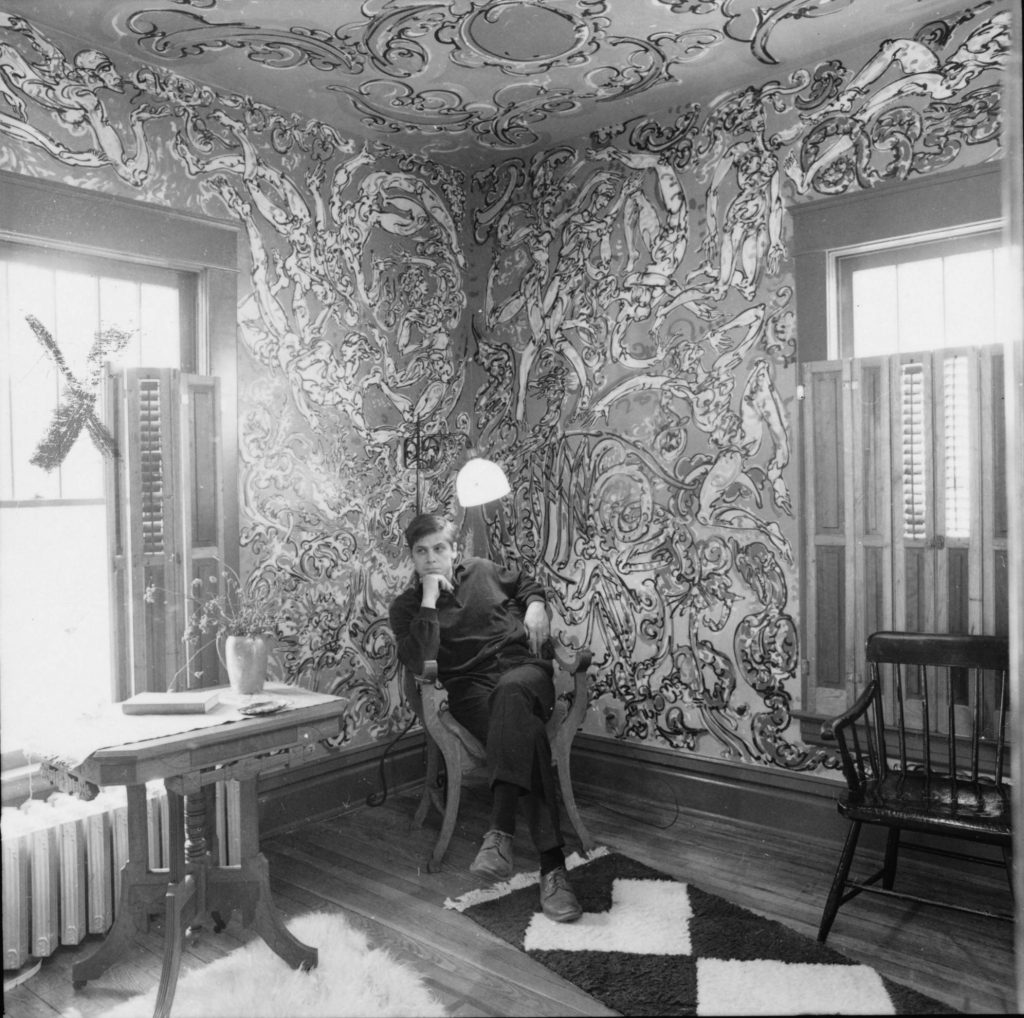

“He painted all over the walls of our house, in the intricate, colorful style of his first (Siegfred) mural,” said Karla, who mentioned that the family is on the hunt for any color photos of the inside of her childhood home or the original mural, which her father completed in the late ‘60s, and is distinctly different from what the mural looks like in contemporary times. “It was all along our walls and stairs and rooms, because he had to have a big canvas. Some of our friends eventually moved into the house and painted over the artwork, which is understandable. It was overpowering, but that was normal for us, to have horses running up the stairs.”

Due to her academic parents and neighbors, Karla was exposed to an explosive variety of art and academic thought, sometimes solely from overhearing complex conversations at her parent’s cocktail parties.

“You’re sitting down, listening to that kind of academic conversation about art, and you’re just surrounded by it,” she said. “And that is a part of dad’s legacy, the appreciation of art that I just grew up with and that I expected, but didn’t find, in the broader world.”

Karla worked a series of government jobs for many years, an occupation that she is currently taking a break from because she found she “couldn’t stand it.”

“I guess that’s something that Dad and I had in common. That and maybe music,” she said, referencing her own band, The Victorious KayBirds. “In fact, the second to last time I saw my father, he was singing, trying to remember the words to an old song – and I knew the song, so we got together and were singing, he had a wonderful singing voice. We were also showing off our whistling; I have a number of childhood memories of my dad whistling in the house.”

Æthelred Eldridge’s artistic style changed throughout his lifetime, eventually settling into the hyper recognizable, geometric shapes accompanied by esoteric texts inspired by William Blake.

“It really impacted my work when Eldridge decided to almost completely drop color out of his work, he didn’t need it, he didn’t have time for it – it was unnecessary,” said Kortlander. “Many of my paintings tend to be black and white too, and some of that stems from when I was in a period of my life when I had very little time and I needed to be painting every day. I had to consider, ‘what do I have time for?’ ‘what do I not need?’ I think Eldridge figured out that what he needed was just some words and forms and not a lot of color. The words he chose to accompany those images have the feel of the graphic he created – they kind of loop back into them and there is a sort of rhythm or a shape or a form to them; hard and soft parts of the words that seem to mesh with.”

Although Eldridge is inarguably important to the art world, he had no intentions of only appealing to people who studied art in an academic sense.

“(Eldridge) affected the people who were business majors, all the people who had to take an art class and didn’t think that they’d do well in drawing or watercolor or ceramics, so they signed up for this class called ‘Art in Your Life,’” said Kortlander. “I’ve had so many people tell me that he was someone who showed them that there is a different way; that they didn’t have to march in a straight line with your thoughts – you can get off anywhere and turn it around, upside down, and come up with something creative – that you can apply creativity to anything.”

McDiarmid cites Eldridge’s deceptively simple group projects assigned to his lecture classes for much of this profound impact.

“I remember one where he had everyone bring in a half of a pair of gloves, and paint an eye on it, and their assignment was to leave these gloves somewhere in the public domain over the next nine days. So here you are, living in Athens, and all of a sudden there is this bloom of these single gloves with eyes painted on them looking at you, asking you a question. This talked about all of us being half-blind and half-able; all of us,” he said. “As you would move through the community you would encounter these gloves and think ‘oh, that’s an odd thing,’ and then you’d see another, and another, and a fourth and a ninth. And then you’d be going after a ball that your child threw under a bush, and there would be another glove with an eye on it, and you couldn’t help but think ‘what is going on here?’ ‘What does it mean to be a palm with an eye on it?’ ‘I’ve seen that before in iconography.’ ‘What is an eye?’ ‘What is a hand?’ ‘Who has the other matching glove?’ These were very simple exercises that (Eldridge) got hundreds of people who were taking a general education class – and who were maybe deliberately selecting classes that were supposed to be easy – to do, that allowed them to encounter profound thinking. I think that Æthelred planted an awful lot of seeds in a lot of fertile soil.”

A memorial service for Æthelred Eldridge will be held at The Ridges Auditorium (Building 23 on The Ridges compound, 100 Ridges Circle, Athens, OH 45701) starting at 2 p.m. on Saturday, December 1.