News

Fracking’s Next Boom? Petrochemical Plants Fuel Debate Over Jobs, Pollution

By: Brittany Patterson | Ohio Valley ReSource

Posted on:

More than 100 people braved freezing temperatures to both listen and have their say in front of Ohio environmental officials at a recent hearing in Belmont County, Ohio. For the three dozen or so people who testified, the stakes were high.

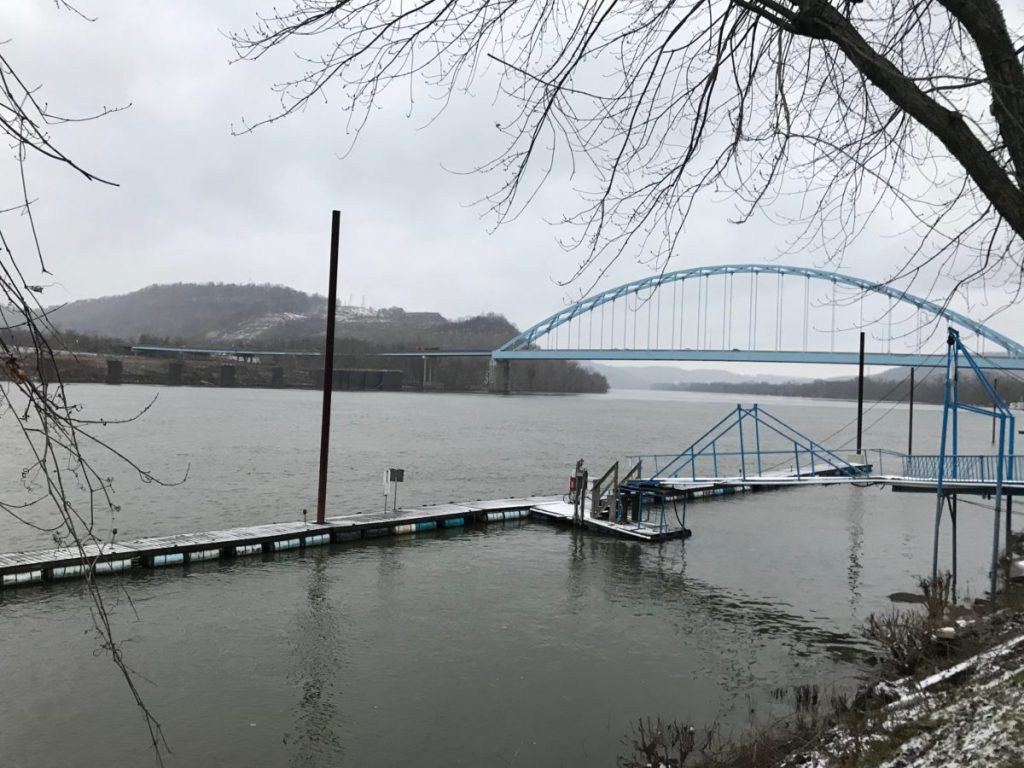

The hearing at Shadyside High School focused on a nearly 300-page, densely technical, draft air quality permit. The permit is one more step towards a massive, multi-billion dollar petrochemical plant proposed for the banks of the Ohio River just a few miles away from the auditorium.

Like many at the hearing, Glenn Giffin, president of IBEW Local 141 in Wheeling, West Virginia, used his three minutes to voice a position not merely on the permit at hand, but what this facility could mean for the region.

“It is a project such as this that will revitalize the Ohio Valley,” he said.

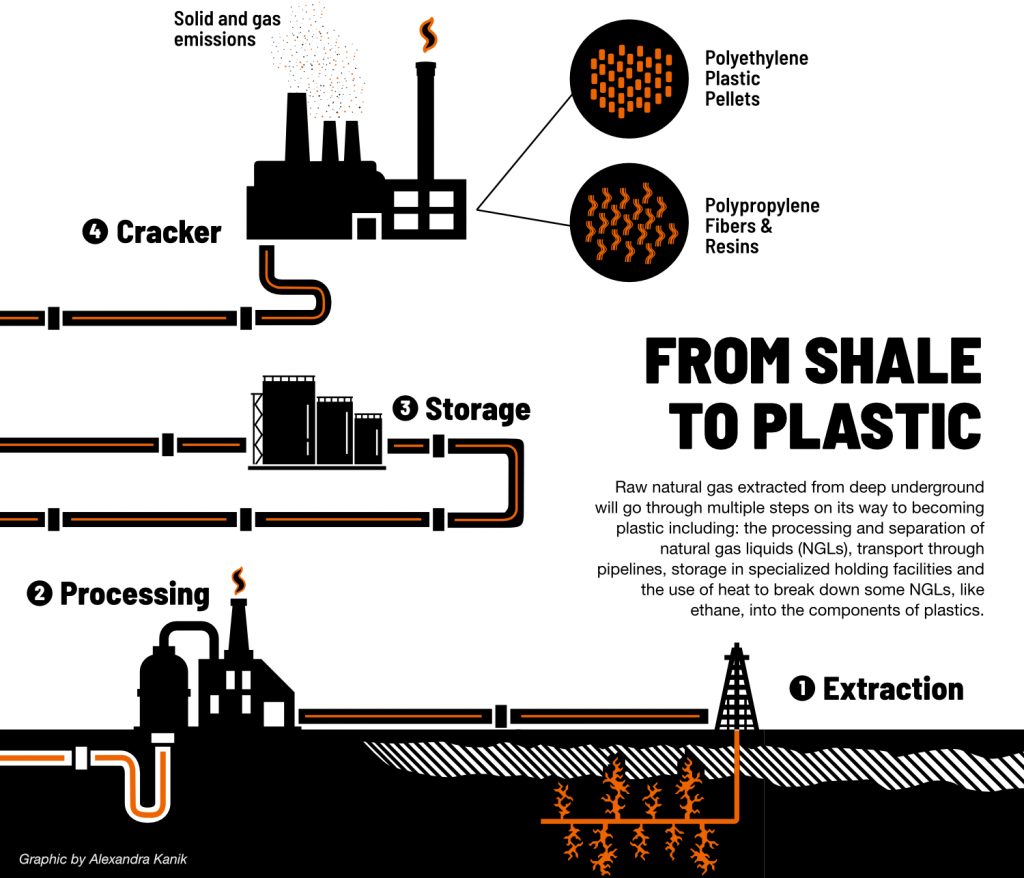

Giffin and other supporters see a potential economic boom in the plant, called an ethane “cracker.” Its natural gas furnaces literally crack apart ethane — which is brought up during natural gas fracking — into smaller molecules used in plastics and chemical manufacturing.

But Belmont County resident Jill Hunkler sees this plant as the beginning of something else: an environmental nightmare.

“We want better options than a massive petrochemical plant,” Hunkler told the audience.

Officially, the hearing was about a permit. But everyone gathered understood that much more is at stake. The growing abundance of natural gas could fuel a new petrochemical industry in the upper Ohio Valley, with all the economic gains and environmental risks that might bring. The decision on the cracker plant permit presents a crossroads moment for those who live here.

Cracker Background

A few years ago, Thailand-based PTT Global Chemical began scouting the Ohio Valley for a location to place a cracker plant.

JobsOhio, a private economic development corporation created by Ohio Gov. John Kasich (R) in 2011 to help woo jobs to the state, worked closely with the company. Matt Cybulski, sector director of energy and chemicals for JobsOhio, said the group helped PTTG select the Belmont County location and put together an incentive package. That included remediation on the site of FirstEnergy’s old R.E. Burger coal-fired power plant that once stood at the proposed cracker’s location.

Cybulski said incentives offered by JobsOhio did not use state tax dollars, but there are tax credits that “can and often are offered to projects like this.”

He and many other state and county officials argue the PTTG project would create jobs.

“Once the plant is built, you have hundreds of good paying jobs that are operating the plant,” Cybulski said. “So, we see this as a long term economic benefit for the local community and the region.”

School district officials have said property taxes paid by the company could bolster local schools.

This year, it was announced that PTTG had partnered with South Korea’s Daelim Industrial Co. on the project and had purchased 500 acres of land in Dilles Bottom, just a few miles from both Shadyside, Ohio, and Moundsville, West Virginia, just across the Ohio River.

A few homes, an apartment complex, a graveyard and a long-shuttered post office dot the unincorporated hamlet of Dilles Bottom.

PTTG’s project is not the first cracker in the region. About 30 miles northwest of Pittsburgh, Shell’s massive Monaca plant is already under construction. The massive petrochemical plant will produce 1.6 million tons of ethylene each year and permanently employ about 600 workers when done, according to the company.

Gas-Powered Growth

If built, the cracker plant in Belmont County could have far-reaching impacts for the entire Ohio Valley, according to energy analysts.

“It’s going to create some real momentum,” said Taylor Robinson, president of PLG Consulting. “There’s going to be some other large petchem companies that will follow suit.”

With that momentum will also come additional infrastructure.

“You’re going to need to have enough wells producing the gas,” Robinson said. “Then you’re going to have to have more gas processing facilities that will separate the ethane out. And then you need storage. Of course you need pipelines between all these things. It’s a complex supply chain that needs to be built for 40 years.”

The Ohio Valley is a prime candidate for petrochemical production because of its geology. The Marcellus and Utica shale formations are loaded not only with methane, the primary component of natural gas, but with more complex hydrocarbons like ethane, propane and butane. In the industry this is referred to as “wet,” and the gas being extracted so readily from the region is often referred to as “wet gas.”

While natural gas is desirable for power generation, the natural gas liquids, or NGL, are separated from their cousin methane to become valuable feed stocks for other industries.

According to a 2017 U.S. Department of Energy report, U.S. NGL production in the region is projected to increase over 700 percent in the 10 years from 2013 to 2023. The report adds, that while the region has made “significant investments” in NGL infrastructure to capitalize on the natural gas boom, more can be done.

“New investments to take advantage of the NGL resources in the region have been identified by industry, and forecasts for production over the decades to come highlight the opportunity for additional investments across the NGL supply chain,” the report states.

One investment is in cracker plants.

The Ohio Valley is ethane-rich, and most plastics and chemicals manufacturers are located in the Midwest. Traditionally, the bulk of the nation’s cracker plants are located on the Gulf Coast.

If Midwestern plastics and chemical manufacturing plants could source ethylene from the Ohio Valley that could reduce cost in an already competitive market, according to Robinson.

Infrastructure Needs

Even if the PTTG project is approved, challenges remain, namely that the Ohio Valley would need to develop more underground storage.

“That is extremely important when you start adding multiple crackers, because as you can imagine, there’s several steps to get the ethane to the plants,” Robinson said. “You need storage along the way, and those storage caverns are a key enabler to have enough flexibility to keep these crackers running 24/7, 365.”

Some storage capacity is under development in the region.

Energy Storage Ventures LLC. is developing the Mountaineer NGL Storage project. When completed, the project would store 2 million barrels of ethane, butane and propane in four underground salt caverns on a 200 acre site, about one mile north of Clarington, Ohio, on the Ohio River.

Another high-profile public-private NGL storage project is also in the works. The Appalachia Storage and Trading Hub cleared its first major hurdle earlier this year, when it got approval for the first of two phases for a $1.9 billion U.S. Department of Energy loan.

China’s largest partially state-owned energy company, China Energy, has pledged an additional $84 billion investment in the region to facilitate the development of a petrochemical industry. The company signed a nonbinding agreement, known as a Memorandum of Understanding, with West Virginia state officials to build a series of facilities that would process natural gas liquids and byproducts. But the escalating trade dispute with China appears to have temporarily slowed progress.

‘Cancer Alley’ 2.0

For a growing number of people, this petrochemical future is not one they want for their communities.

Hours before the Ohio EPA air permit hearing, Martins Ferry resident Barbara Mew was powering through biting cold temperatures and snow flurries to go door-to-door in a neighborhood of Moundsville sharing information about the proposed project.

“I think I’ve pushed through to the other side,” she says laughing. “It’s not cold anymore.”

She worries about what types of pollution the huge plant will emit into the air and water. The draft air permit before Ohio EPA estimates the cracker will release almost 400 tons of volatile organic compounds each year. The plant would also produce the equivalent carbon dioxide emissions of putting about 365,000 cars on the road.

“It’s just it’s an environmental nightmare from top to bottom,” Mew said. “There are really no upsides to it.”

Opponents to the plant expressed concerns at the Ohio EPA hearing that the proposed air permit does not do enough to protect public health, despite assurances from agency officials that the plant would install top-of-the-line technologies to limit emissions.

According to the permit, nitrogen oxide and carbon dioxide emissions will be continuously monitored, but other pollutants will only be tested intermittently. Many people expressed concerns that PTTG is not required to do fence line monitoring, or to actively track what is being emitted from the plant. They are also concerned that the one air quality monitor that is installed in the county would not be sufficient to alert local communities of any pollution above permitted levels.

Many asked for a health impact assessment to determine the potential public health effects of the facility and for Ohio EPA to conduct a cumulative assessment of air emissions that would account for future natural gas industry infrastructure spurred by the PTTG plant.

Ohio EPA hearing officer Kristopher Weiss said the agency’s jurisdiction is fairly narrow and requires the agency to take action on permits within a set period of time. If the PTTG plant goes into operation and spurs additional developments, he said Ohio EPA would evaluate each new project on an individual basis.

“If PTT were to get its permit, and then other ancillary business were to come in, if those businesses need permits they would apply for whatever permits they might need and the agency would take the action they are required to take,” he said.

Lea Harper, managing director of the nonprofit Freshwater Accountability Group, which organized the canvassing effort, said the volunteers knocked on hundreds of doors and found most people have concerns. A big one is that the Ohio Valley could turn into the next “cancer alley.” The term refers to the huge and heavily polluted belt of chemical manufacturing facilities in Louisiana.

“I don’t understand why fossil fuel extraction, why that’s the only kinds of jobs this area is offered,” she said. “We want jobs that won’t kill us.”

Cumulative Effects

Retired public health practitioner Susan Brown sat in Van Dyne’s, a diner located on the outskirts of Shadyside known for its all-you-can-eat spaghetti. She says she worries about what will happen to her community.

“The fracking plant came in. Then we’re talking about the cracker plant. They’re talking about the underground tanks,” she said, sipping an unsweetened tea. She’s concerned that her town is approaching a point where it will be “an area that nobody wants to live.”

Brown says most people she talks to about the cracker plant feel like it’s a done deal. Still, she says it’s important to speak out.

A public hearing regarding the plant’s water permit hosted by Ohio EPA is scheduled for Wednesday, December 12, at Shadyside High School.