Communiqué

“The Swamp” on AMERICAN EXPERIENCE | Tuesday, January 15 at 9

< < Back toAMERICAN EXPERIENCE

The Swamp

Premieres Tuesday, January 15, 2019 on PBS

A Story of Greed, Hubris and Destruction, The Swamp Chronicles the History of Florida’s Everglades, the Deadly Quest to Conquer It, and the Ensuing Drive to Save It

A Story of Greed, Hubris and Destruction, The Swamp Chronicles the History of Florida’s Everglades, the Deadly Quest to Conquer It, and the Ensuing Drive to Save It

The Swamp tells the dramatic story of humanity’s attempts to conquer the Florida Everglades, one of nature’s most mysterious and unique ecosystems. Told through the lives of a handful of colorful and resolute characters, from hucksters to politicians to unlikely activists, The Swamp explores the repeated efforts to transform what was seen as a vast and useless wasteland into an agricultural and urban paradise, ultimately leading to a passionate campaign to preserve America’s greatest wetland. As the world copes with increasingly deadly weather events, The Swamp is a timely tale of the perils of mankind’s abuse of nature. Based in part on the book The Swamp: The Everglades, Florida, and the Politics of Paradise by Michael Grunwald, The Swamp is produced and directed by Randall MacLowry and executive produced by Mark Samels. The film premieres on AMERICAN EXPERIENCE Tuesday, January 15, 2019, 9:00-11:00 p.m. on WOUB.

Home to a profusion of plants and animals found nowhere else on the continent, Florida’s Everglades was an immense watershed covering the southern half of the Florida peninsula. But to most progress-minded Americans, the Everglades was a useless swamp filled with deadly diseases and vile reptiles. Entrepreneurs and politicians saw great potential in draining the Everglades and turning the massive wetland into a profitable enterprise.

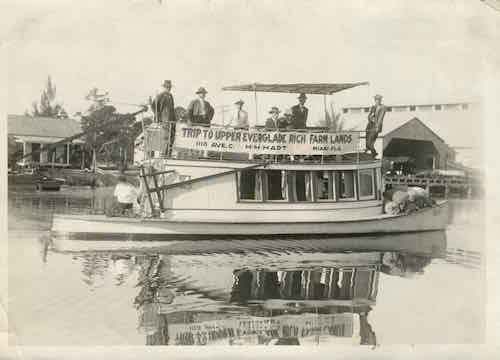

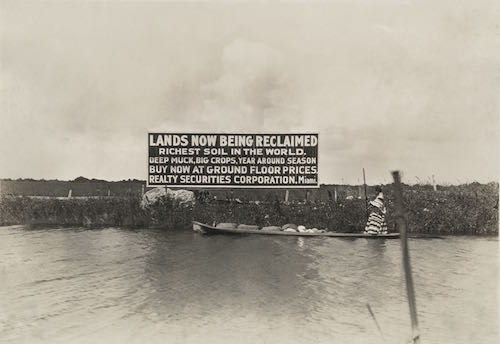

Philadelphia industrialist Hamilton Disston was the first to make a serious effort to drain the Everglades. In 1881, he purchased four million acres of swampland from the state, dug canals that opened up dry land, and attracted newcomers, but a season of heavy rains flooded farms and frustrated his plans. Governor Napoleon Bonaparte Broward, who took office in 1905, promised to finish what Disston had started. Though Broward only reclaimed 12,000 acres while governor, he convinced people that the Everglades could be drained. As he exited office, Broward sold a huge tract of the Everglades to land speculator Richard Bolles to keep his project on track. Promising that the whole of the Everglades would be drained in a year, Bolles sold thousands of parcels sight unseen to would-be farmers and settlers from all over the country. Many new landowners soon discovered that their investment was still underwater. “I have bought land by the acre, and I have bought land by the foot,” said one purchaser, “but, my God, I have never bought land by the gallon.”

Philadelphia industrialist Hamilton Disston was the first to make a serious effort to drain the Everglades. In 1881, he purchased four million acres of swampland from the state, dug canals that opened up dry land, and attracted newcomers, but a season of heavy rains flooded farms and frustrated his plans. Governor Napoleon Bonaparte Broward, who took office in 1905, promised to finish what Disston had started. Though Broward only reclaimed 12,000 acres while governor, he convinced people that the Everglades could be drained. As he exited office, Broward sold a huge tract of the Everglades to land speculator Richard Bolles to keep his project on track. Promising that the whole of the Everglades would be drained in a year, Bolles sold thousands of parcels sight unseen to would-be farmers and settlers from all over the country. Many new landowners soon discovered that their investment was still underwater. “I have bought land by the acre, and I have bought land by the foot,” said one purchaser, “but, my God, I have never bought land by the gallon.”

Nevertheless, some settlers began to clear away the native vegetation to plant crops like celery, lettuce, tomatoes and strawberries. In the 1920s, Miami and other south Florida coastal cities experienced an unprecedented real estate boom, selling sunshine and tropical paradise to vacationers and retirees.

Other voices began to question the constant call to “drain and develop” the Everglades. Naturalist Charles Torrey Simpson warned of the dangers of despoiling the area’s beauty and biodiversity for the sake of progress. But it was a group of well-connected women who would be the first to protect a piece of this unique wilderness.

To many, expanding efforts to drain the Everglades were signs of progress. To others, they were a menacing intrusion. In the early 1800s, the Seminole had found refuge from encroaching white settlement in the Everglades, fighting a series of bitter wars to resist removal from Florida. By the early 20th century, dredges crisscrossing the wetlands had upended the Seminole’s way of life.

A ltering the landscape of the Everglades also unleashed a torrent of unintended deadly consequences, from catastrophic floods to brutal droughts. In 1926, a devastating hurricane struck south Florida and turned Miami’s boom into a bust. Two years later, another violent hurricane pushed the waters of Lake Okeechobee over the top of its flimsy muck dike and drowned 2,500 people, mostly black migrant laborers from the Deep South and the Caribbean. The 1928 Lake Okeechobee Hurricane would become the second deadliest natural disaster in American history.

ltering the landscape of the Everglades also unleashed a torrent of unintended deadly consequences, from catastrophic floods to brutal droughts. In 1926, a devastating hurricane struck south Florida and turned Miami’s boom into a bust. Two years later, another violent hurricane pushed the waters of Lake Okeechobee over the top of its flimsy muck dike and drowned 2,500 people, mostly black migrant laborers from the Deep South and the Caribbean. The 1928 Lake Okeechobee Hurricane would become the second deadliest natural disaster in American history.

As attempts to conquer the Everglades continued to wreak havoc on the environment, efforts increased to preserve and understand this vital ecosystem. Ernest Coe moved to Miami in 1925 and fell in love with what remained of the Florida Everglades. Creating a large national park became his life’s work, and he drew many other influential people into his cause, including Miami Herald writer Marjory Stoneman Douglas, who publicized the national park campaign and would become one of the most passionate and effective advocates for the Everglades. Their efforts paid off and, in 1934, President Franklin Delano Roosevelt signed a bill authorizing the creation of Everglades National Park.

But it would be Marjory Stoneman Douglas’s landmark book The Everglades: River of Grass, which forever redefined the region as essential not only to wildlife but to people. In the decades that followed, the interests of conservation and development continued to compete in an area where boundaries were, and are, fluid. “It really is a moral test,” observes journalist and author Michael Grunwald on the future of the Everglades, “of whether we’re going to be able to preserve a place for people alongside a unique creation of wilderness.”

“The Swamp tells an epic tale of man’s never-ending attempt to control nature,” says AMERICAN EXPERIENCE executive producer Mark Samels. “The story of the repeated efforts to tame the Everglades — and the often deadly results of those attempts — is a particularly cautionary tale in these days of increasingly violent natural disasters.”