Culture

OU’s Basil Masri Zada Is An Accomplished Academic and Artist Who Cannot Return Home

By: Rachael Beardsley

Posted on:

Basil Masri Zada has not seen his family in Syria for eight years.

War has kept him from returning, and in his absence, much of the Syria he remembers has been erased. Yet those memories come alive again through his artwork.

Masri Zada’s art seeks to critique the conflict in Syria from a scholar’s point of view, giving equal criticism to all sides. He analyzes the conflict from a distance and tries to understand what has changed since he last set foot in his home country. Often, the story he tells is a deeply personal one. In “The Truth Project,” for example, he chronicles the effects of the Syrian civil war on his own life. Similarly, the performance piece “Walk of Respect” was inspired by the loss of a friend in Syria.

“My artwork is trying to educate people [about] what’s happening and, at the same time, a healing process to me,” Masri Zada said. “I try to express what it means to be Syrian… with all of these stereotypes in relation to religion, refugee crisis and even the simplest thing of the danger of being Syrian.”

Aside from being a practicing artist, Masri Zada is also a Ph.D. candidate and instructor in the interdisciplinary arts program at Ohio University. As a fourth generation artist, Masri Zada spent much of his life learning, observing and practicing art. Though he considered studying chemistry, he ended up attending Damascus University as an art student and eventually became a full-time tenure track professor assistant.

“In teaching and in art I never feel like I’m working,” Masri Zada said. “I’m enjoying it; I’m having fun with my students. It’s fun, it’s overwhelming, but it’s the most fun I have in anything.”

Masri Zada decided to study in the U.S. for his Master’s degree and was awarded both a scholarship from Damascus University as well as the prestigious Fulbright Scholarship from the U.S Department of State. He planned to return to Syria once he finished his degree, but not long after he arrived in the U.S. in 2011, the political situation in Syria escalated and relations with the U.S. got worse. As a result, Damascus University demanded he return to Syria.

“That’s when I cut all connection back there, and I decided to stay,” Masri Zada said. “It took me two years to prepare for the Fulbright, and it’s one of the highest honors in the world, and then I’m just being requested officially to drop all of this and not to participate. It’s like throwing two years of my life away. So I decided to stay and leave everything there.”

Since arriving in the U.S., Masri Zada has been issued temporary protection status from the Department of Homeland Security, meaning that, while not considered a refugee or asylee, he is still protected from being removed from the U.S. until the situation in Syria gets better. Every 18 months, however, he has to pay a fee of almost $500 to renew the status, and is unable to return to Syria or leave the U.S. The huge amount of temporality in his situation doesn’t allow him to progress as an artist in the ways he would prefer. The Syrian passport, he says, is sometimes like a curse.

“With this temporality, it’s make it uncertain,” Masri Zada said. “Even as I’m living outside of that conflict, I’m affected by the consequences in my daily life right now.”

Masri Zada’s continued connection to the conflict inspired one of his first performance art pieces. In “Attached/Tied,” he used string to tie himself to the American Civil War monument on College Green. The work was meant to express his connection to the concept of civil war and to the conflict in Syria even while physically separated from it.

“It’s affecting my everyday life routine,” he said. “I wake up in the morning to read the news, I call my parents to make sure they are safe, so I’m still attached to that even if I am trying to escape it. I cannot be separated from it because my life, everything, is… all back home. I just cannot live without thinking about all that. So [the performance art] was symbolic, no words, and it was just trying to have this meditation with that concept.”

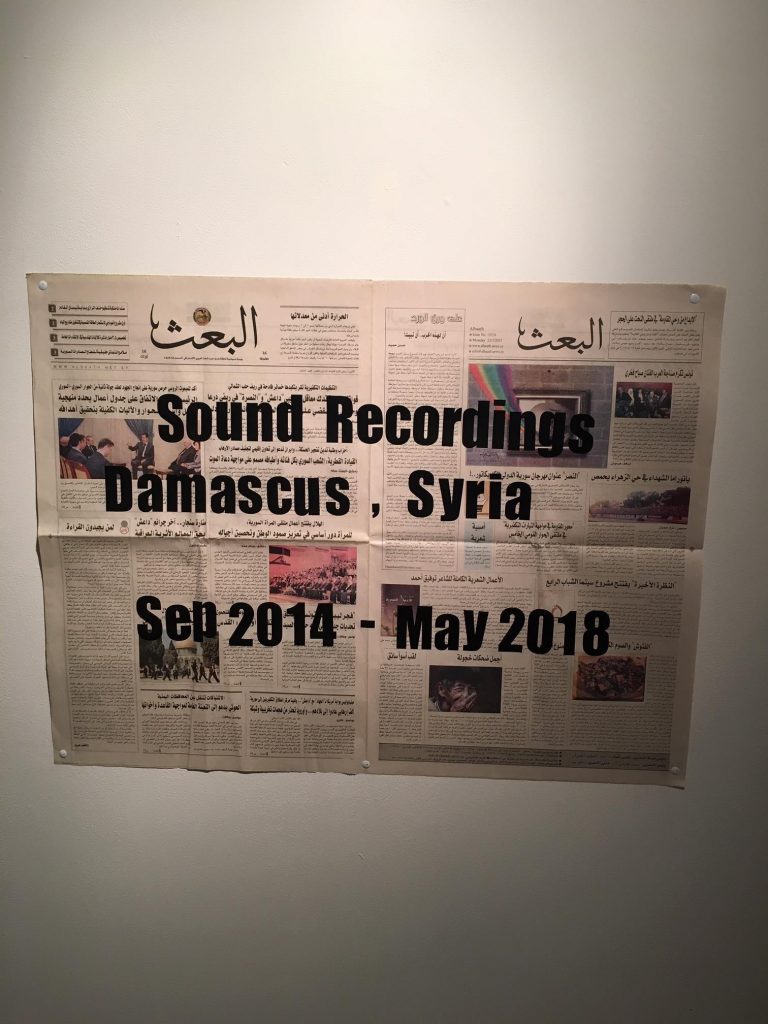

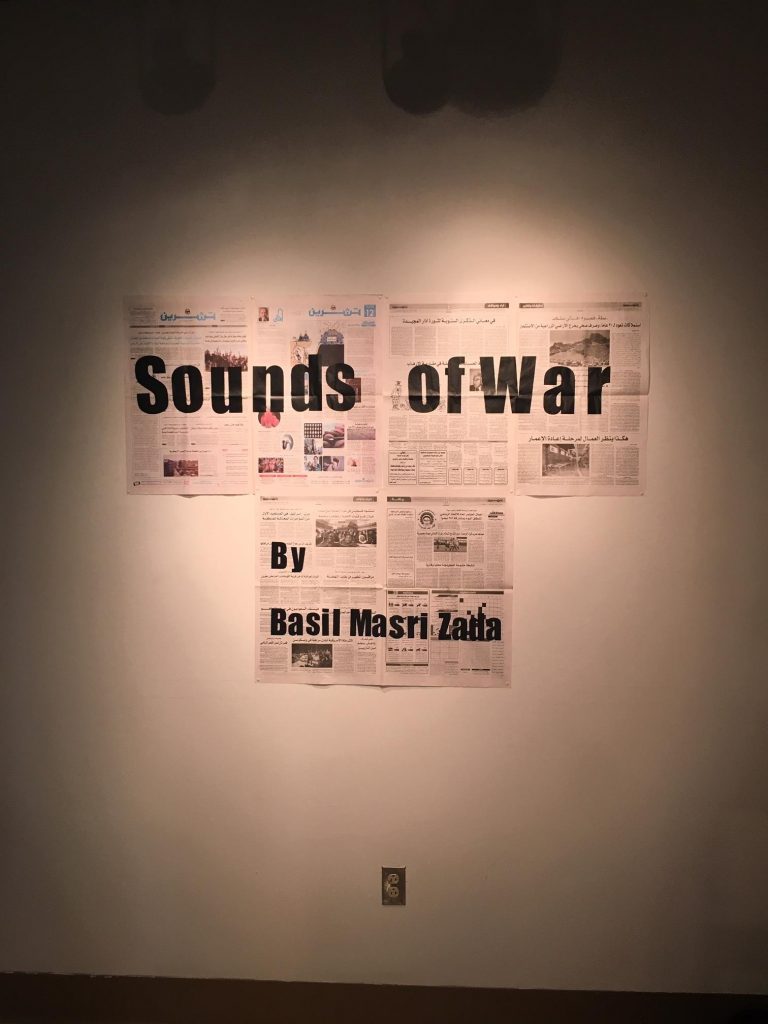

Since that first piece, Masri Zada’s work has continued to explore his connection to Syria and what it means for his life in America. His latest project, called “Sounds of War,” is set to be displayed in the Trisolini Gallery from January 22 to February 2. The project began after a phone conversation with his family. In the background of the call, he could hear gunshots and other artillery fire in the distance. His family, however, told him not to worry. They were used to it.

“They got numb to it, but for someone from outside to hear this, how many of us actually listen to an actual artillery shelling happening?” Masri Zada said. “An actual air strike?”

He asked his family to take audio recordings at different points during the day, and then he cut the audio to showcase the noise of battles beneath daily life. He has between 100 and 300 recordings from the last four years, all of them made on the balcony next to his childhood bedroom.

“The nostalgia of that room compared to the sound of battles, that’s the project that I’m so passionate about right now,” he said. “In the background, you could hear plates being prepared, which I know is my mother preparing food. You could hear in some videos mosques praying or the bells from the churches, and you can hear the cars in the rush hour and you can hear kids playing. You could hear that the will to live—it still exists just by listening to the sounds between these sounds of war.”

Although they have regular phone conversations, Masri Zada has not seen his mother, father or sister in eight years. He has a one-year-old nephew who will probably grow up without him. Because Syrian families are very close-knit, the divide is a challenge for Masri Zada, especially when days pass without a new call.

“Not seeing them is one thing, but not knowing if they are well or if they will be well is another thing, and that’s part of why you need something to take all this worry, all this pressure, to something else,” he said. “That’s when art came as a way for me to process this.”

One family member was eventually able to join him in the U.S., although the process was incredibly difficult. Masri Zada’s wife obtained her visa in 2013, but not before the two got married while in separate countries. Because of a Syrian law that allows marriage through a special power of attorney, Masri Zada’s father was able to sign the marriage license for him. The six-month process involved translating and re-translating paperwork and then mailing it through a system of many different cities and notaries. For one of his art pieces, Masri Zada photoshopped pictures to show him and his wife together, though in reality he was not able to attend his own engagement party.

“Imagine a bride in her wedding by herself while her husband is 6,000 or 5,000 miles away in a different country,” he said. “So everyone should be happy, but they are not because we are apart.”

Masri Zada and his wife were able to hold a small, private ceremony once she arrived in the U.S. They now have a four-year-old daughter. Masri Zada says he struggles to find a way to talk to her about home. The question, he says, is whether to tell her about the “happy nostalgia” of his childhood in Syria or explain how everything has changed.

“That’s the big question,” he said. “She is American, she’s born here, she speaks only English. She’s Syrian, but she knows nothing about Syria. So what should I tell her about home? Tell her about my history in Syria or about political conflict? What would home be for her? That’s the hardest question to think about.”

The media stereotyping of Syria and the Syrian people, he says, only makes the question that much harder to think about. Masri Zada has known children born to Syrian immigrants who refuse to believe that Syria is anything other than a desert wasteland.

“Stereotyping what it means [to be] Syrian is the big problem Syrians have from the travel ban,” he said. “A Syrian passport now is almost useless. I could count the countries that allows Syrians to go right away in one hand, so that’s part of the exaggeration of the stereotype, too.”

Masri Zada’s body of work seeks to counteract those stereotypes. At the heart of his work is what it means to be Syrian despite the conflict and because of it. Masri Zada focuses on the humanitarian aspect of the war, something that is often drowned out by politics and statistics. Particularly, he explores his own perspective as someone intimately connected yet separated from the war.

“Each media station has its own goals or an institution that show only one part the story,” he said. “The unique perspective [is] when a Syrian artist talks about the Syrian crisis. That’s what my activism is trying to understand—how I’m being affected by this even if I’m not living in the country. I have my own crisis because of that crisis, and [I’m] trying to understand and explain that crisis.”