News

Serving Survivors: In Rural States, Telemedicine Brings Treatment For Sexual Abuse

By: Mary Meehan | Ohio Valley ReSource

Posted on:

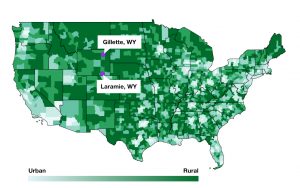

Gillette, Wyoming, isn’t the kind of place you just happen to come across.

“It’s about a four hour drive through vast, unimpacted, wide, sweeping plains,” said Matt Gray, a professor at University of Wyoming in Laramie, explaining the trek from his office to his clients.

Plains, he said, “and lots and lots of antelope.”

For the last decade, Gray and graduate students have bridged the space across the high plains with a digital connection in order to serve survivors of domestic violence and sexual abuse.

The university town of Laramie connects with the boom and bust energy town of Gillette near the South Dakota border providing specialized trauma counseling. Without that link no such service would be available.

Margie McWilliams is director of what is officially called the Gillette Abuse Refuge Foundation and unofficially called GARF. In her estimation the therapy program has been invaluable.

“Honestly, it has saved a lot of lives.”

Since the #MeToo movement started a national conversation about sexual violence, the scope of the discussion continues to grow from exposing the issue to exploring how to best help survivors. Those include rural women who are often underserved and overlooked. Each place is different but many rural communities, including those in the Ohio Valley, share the challenge of providing services when there are lots of miles between people and providers.

Underserved, Overlooked

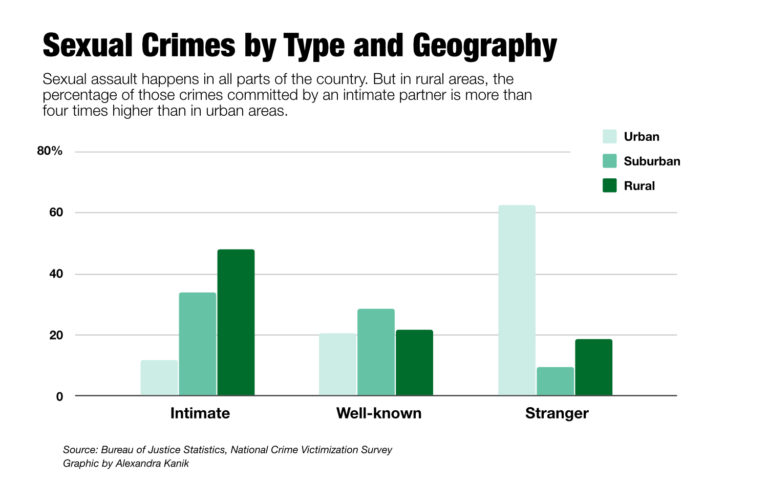

Historically, much of the research on domestic violence and sexual assault has centered on urban areas. But a study published in the Journal of Women’s Health shows that women in rural areas suffered a higher rate of intimate partner violence than their urban counterparts.

Not only is there more violence, it is less frequently reported. A 2016 report from the Justice Department noted that in rural areas only 41 percent of violent crime and 47 percent of serious violent crimes (defined as rape or sexual assault, robbery, and aggravated assault) are reported to the police.

An earlier study explored reasons that people did not report these crimes: it was considered a personal matter; such an assault was not considered important enough to report; victims felt the police would not or could not help; and victims fear of reprisal or getting the offender into trouble.

These findings are not news to McWilliams or Gray, who between them have nearly 50 years of experience in dealing with domestic violence and sexual assault in rural communities.

Rural Similarities

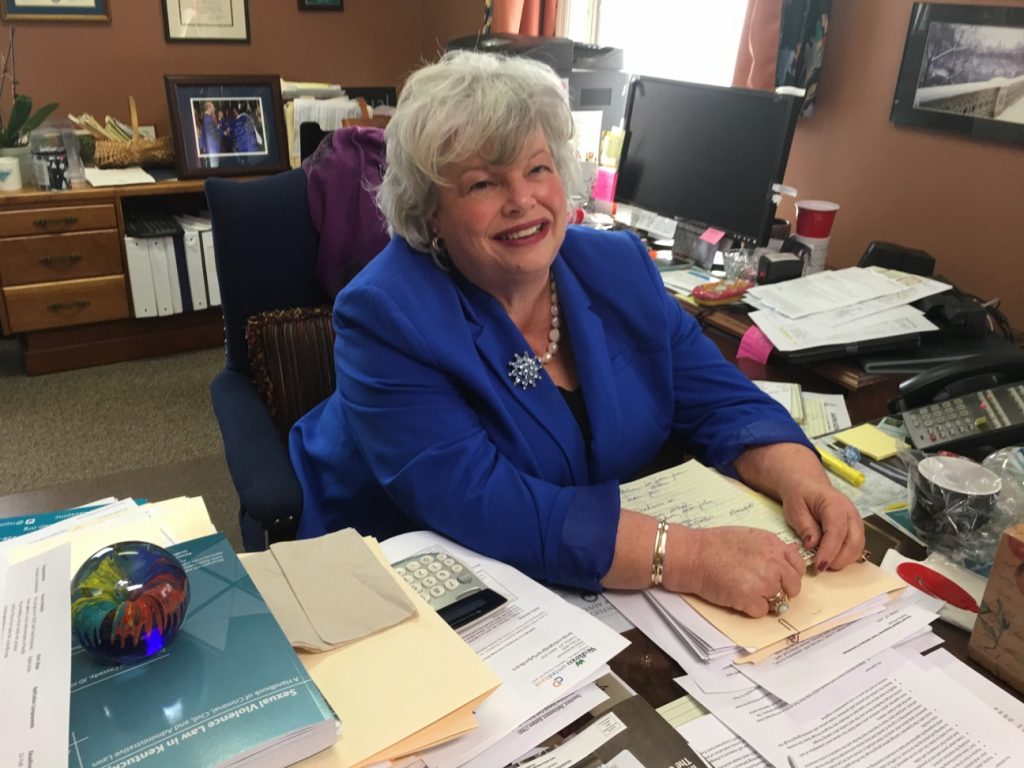

Eileen Recktenwald is executive director of the Kentucky Association of Sexual Assault Programs. She said access to quality care has been an issue for the 35 years she has been an advocate. She said she could see a telehealth program working in the Ohio Valley.

Already, she said, younger people, especially ages 18 to 24, are seeking services in a different way. “They are much more electronically inclined and access services via chat or the internet,” she said.

Rural communities don’t all look the same. Wyoming’s wide open spaces, as people there like to say with some pride, make it one of only two states determined to be not only rural but uber-rural, or “frontier.” (The other frontier state being Alaska.)

But there are similarities between the plains in the west and rural parts of Kentucky, West Virginia, and Ohio.

Recktenwald said most rural parts of America share some common traits. They also have similar barriers to mental health care because they lack services and providers, face transportation barriers, and have cultural factors that can cause social stigma to be amplified.

Telemedicine, as a whole, is becoming a routine part of healthcare. According to a recent report from the American Hospital Association, 76 percent of hospitals offer some kind of telehealth service. Last year, the Veterans Association launched a telehealth initiative for service members with PTSD.

But as Gray points out, the best ways to approach rural women and combat veterans are not the same. And, he said, there are other things to consider.

Why Wyoming

Gray went to college to be a dentist but soon found a passion for psychology and has specialized in sexual abuse and domestic violence for more than 20 years. With a dark beard and an easy smile, he’s the kind of guy who frequently says, “that’s a great question,” yet manages to always sound sincere.

The university’s information technology department first brought the idea for a telehealth clinic to him. They had received grant money for telehealth but couldn’t find the right focus.

Gray said he was a little worried at first that he wasn’t tech savvy enough to oversee a digital operation. Now he rolls with the lingo.

“It was a matter of having them help set up a polycom unit that is secured and encrypted video conferencing at the distal site,” he said.

Translated, that means there is a secure computer in one place that connects to the same in the other. Those computers can only talk to each other and no one else can listen. Securing privacy is a key element given the subject of the conversations that will take place on these links.

The first clinic was in Rawlins, a town of just under 9,000 people. Rawlins already offered domestic abuse services but not therapy. Gray said only one or two clients in Rawlins access telehealth each year. Some clients come from the state’s biggest city, Cheyenne, but most come from Gillette.

Gray said he had some reservations in the beginning as to whether the person-to-person experience of counseling could be replicated in a remote and mediated setting. His research shows the clients are often more satisfied with their experience than are the therapists.

“The baseline is different because the client isn’t comparing the telehealth experience to previous counseling,” he said. For them, he said, “it’s how does this compare to getting nothing at all, which would be the only alternative.”

Student Help

Another important piece is the graduate students who make up the therapy team.

Two current team members are Kendal Binion from Georgia and Stephanie Amaya from Los Angeles.

After working together closely for two years, they frequently laugh in unison and finish each other’s sentences. It is a bound forged, they said, in doing the difficult work of providing therapy to rural survivors of sexual assault and domestic violence.

Binion said she applied to the program while working as a hospital advocate where she helped connect clients to services but didn’t provide therapy.

“What I saw was a lot of victim-blaming from not only medical providers and police officers, but from family and friends,” she said. “And I really wanted to reach out and go beyond advocacy.”

Binion gets tears in her eyes as she talks about one Wyoming client who made a lasting impression. The woman had kept the secret of her assault to herself for decades, telling no one.

“All of these cases are hard, but to have someone who had the added pain of no support,” Binion said, “it was also exceptionally hard to hear that it was for 40 years.”

Amaya said she’s been inspired by her clients. “They are the ones making those steps first,” she said.

Those first steps involve escaping the extensive control exerted by the partner. That can include, she said, the lack of access to money, the lack of the ability to leave the house, threats to take away children, and the very real possibility of additional physical or sexual violence.

The geographic isolation of a rural setting can compound those effects, she said.

“Part of that cycle of violence is isolation that the perpetrator tries to inflict on the victim, whether that be from family or from resources,” Amaya said. “And geographic isolation just really fits perfectly into that model.”

But she said therapy can work even if it is happening across a computer network instead of across the room.

“I found that human connection is transcendent,” she said. “It doesn’t depend on proximity. It depends on empathy, and a willingness to share and to open up and to support someone who needs that support.”

Finding Funding

Telehealth is not the perfect solution in rural areas, Gray said. First, there’s the question of funding.

“It goes without saying that in terms of getting dollars in resources for sexual assault and domestic violence, no matter what kind of service you’re trying to provide, that’s a really hard thing to do,” he said.

Plus, he said, most available grant money is tied to innovative uses of technology for a limited number of years. There is less funding available to sustain the work of treating trauma.

There are plenty of other rural communities that would benefit from such a program, he said. But there is also a limited number of appropriate therapists-in-training. His program can serve about 20 to 25 clients at a time. Those clients receive, on average, 12 to 15 sessions.

What you don’t want to create, he said, is a service with a far reach but a long wait time.

He said that to tell a domestic violence or sexual assault victim “’we can get you but it is going to be two or three months’ is highly problematic.”

The goal of the current team is to contact a client within the first 48 hours after the first report and to have the first session with the client within 96 hours.

The need for more services, he said, is always there. “Unfortunately up until very recently mental health services has been deemed kind of a luxury,” he said.

Even the rate of sexual assault and domestic violence is not well understood in the broad community, Gray said.

He conducted a study of 2,000 University of Wyoming students on incidents of sexual misconduct, partner violence, domestic violence, sexual harassment, and stalking. The study found 27 percent of students had experienced sexual abuse. People outside of the field of study might find the results “eye popping,” he said, but “while they are tragic, they are not atypical.

“So, I do think we still have this disconnect between people who recognize how common this is — and that’s been replicated again, and again, and again — versus people who are just finding out about the magnitude of this problem for the first time,” he said.

A #MeToo Effect

McWilliams has been at the Gillette Abuse Rescue Foundation for most of its three decades. Shawna McDonald has worked there for 15 years.

The two women are self-described left-leaning advocates in a deeply red community. They are carrying on work that began when “host families” took in victims of domestic violence in private homes back in the 1970s.

They said getting survivors into the building so they can use the telehealth service involves pushing back against cultural norms that encourage silence.

Gillette is a boom town dependent on the cyclical nature of the energy business. Because of that, the locals welcome outsiders out of economic necessity. But that has its limits, McWilliams said.

McDonald said the families that came to the region generations ago, called the “homesteaders,” still hold political sway.

“We always we call it the Good Ol’ Boy system here because, you know, men run our government.”

She said when a female GARF board member recently talked about running for a county office, one male elected official told her “we won’t be letting any little ladies” win elections.

But, they said, #MeToo is having an effect, even out on the high plains. McWilliams said they are seeing more young people seeking help.

There is something else, a cultural shift that is both quiet and broad. In January about 60 people turned out for a Women’s March in Gillette. McWilliams and McDonald said that kind of support matters.

“So to me that was a big thing that’s changed. We’ve never had that many people involved before. And of course, we got the trucks that drove by and you know flipping people off,” they recalled in unison. “But it was cool because nobody cared. We were just there for a reason and we have seen an increase in our services and sexual assault victims are coming in.”

People from more rural parts of the state came to the march. That included two moms who brought their daughters from the next town over, Sheridan. It’s 104 miles, one way.

Support for this story came from the Solutions Journalism Network.