News

Cannabis Economy: With Medical Marijuana, Ohio’s Meigs County Hopes To Cash In On “Golden” Opportunity

By: Aaron Payne | Ohio Valley ReSource

Posted on:

Meigs County, Ohio, has a complicated history with marijuana.

“Meigs County Gold” has been grown illegally for years. Local legend has it that was the strain of choice for musicians like the Grateful Dead and Willie Nelson when they toured Ohio.

But for Meigs County Commissioner Randy Smith, that isn’t a source of pride. Instead it felt like a target on his back.

“If you were going to the Columbus Zoo or Kings Island, lock your cars,” he said. “Because people see the Meigs County tag and it was almost inevitable you’d have busted windows. And the idea was they were looking for marijuana.”

In 2016 Ohio became the 26th state to legalize medical marijuana. That means Smith and other Meigs County residents are changing the way they think about the plant.

Smith is not an advocate for marijuana. But the decline of coal in this Appalachian corner of Ohio has brought a loss of tax revenues and employment. Meigs County consistently is in the top ten of highest unemployment rates in the state at around 8 percent.

The place once famous for illegally growing a “gold” strain of marijuana is hoping to cash in now that it is legal to grow for medical use.

“So all these big job creators that we did have are no longer there,” Smith said. “So where else do you tap from? It’s got to be a place that you didn’t have it from before. It’s either going to be technology or it’s going to be something brand new like this.”

A Cannabis Economy

Local officials around the Ohio Valley are rallying around medical marijuana for its potential economic benefits. Delays in state programs and limits on licenses, however, make it difficult for rural communities to cash in.

Kentucky has yet to legalize medical marijuana, but legislation seems to progress a little each year.

A GOP-controlled committee passed House Bill 136 this session but the bill stalled out before the legislative session ended.

West Virginia legalized medical marijuana in 2017 after Gov. Jim Justice signed the Cannabis Act.

Legislators returned to the issue in this past legislative session to offer two major fixes to the program. House Bill 2538, which was signed by the governor, allows financial institutions in the state to handle funds generated by the program. (Federal law considers accepting funds related to marijuana sales as money laundering.)

House Bill 2079 passed both chambers with bipartisan support and clarified the Cannabis Act to allow a business to grow, produce and dispense its own products. But Gov. Justice vetoed this bill, claiming it favored “vertically integrated” businesses.

Justice wrote in a veto message that he fears only a few companies would be able to profit from the state’s program and wants to see lawmakers come back with classifications that are “reasonable.”

Del. Mike Pushkin, a Democrat from Kanawha County and the lead sponsor of the bill, said he was disappointed with the governor’s decision.

“Without this legislation, cannabis business accounts will remain empty, suffering people will remain untreated, and badly needed tax revenue will go unrealized,” he wrote.

Officials estimate it could be three years or more before patients can purchase medical marijuana in West Virginia.

This leaves Ohio as the only state in the Ohio Valley with an operational medical marijuana program.

Patients with one of 21 qualifying medical conditions began to purchase marijuana when the first dispensary opened on January 16.

Early results show why people like Smith are pushing hard to get into the new industry.

Big Pot-ential

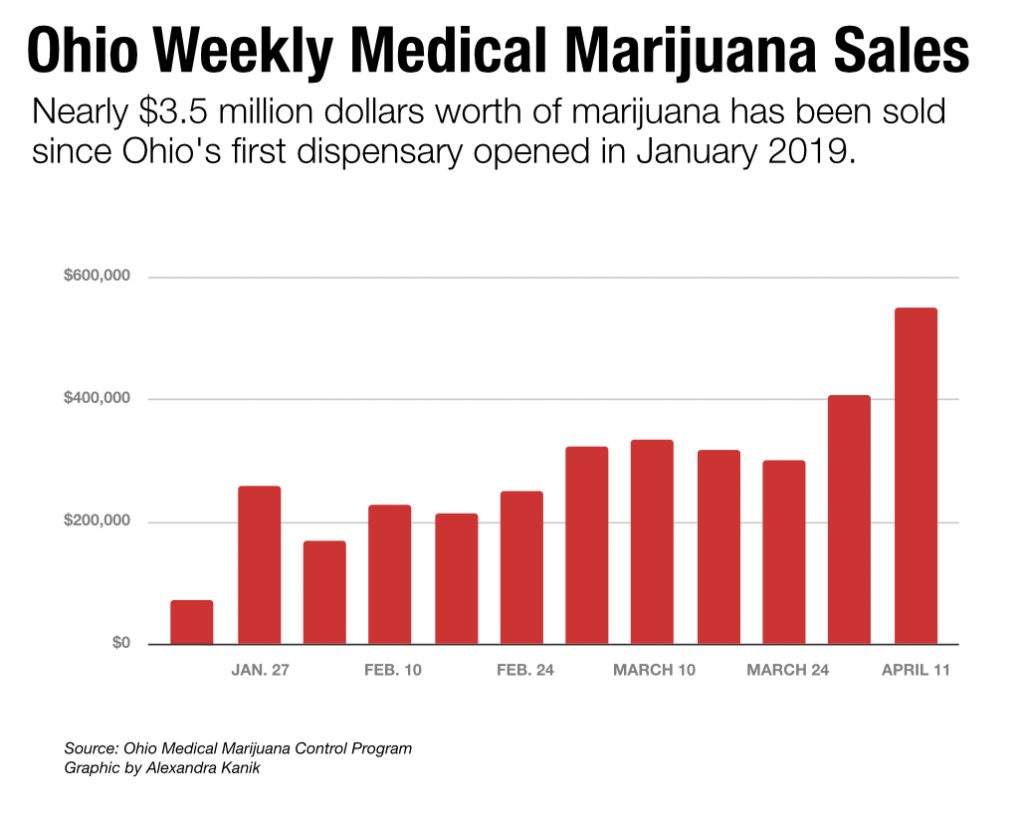

Medical marijuana generated nearly $3.5 million in sales since the first dispensary opened.

That’s according to the state Department of Commerce, one of the three state agencies that makes up the Medical Marijuana Control Program.

Mark Hamlin, a senior policy adviser with the department, provided the figures at a Medical Marijuana Advisory Committee meeting on April 11 in Columbus.

Officials watching the program are pleased with the numbers, considering marijuana has only been available in flower form (and can’t be smoked, per state law) for a majority of the program’s existence.

“We definitely think that there have been people who were waiting until there was manufactured product before they would sign up, certainly before they would go buy,” Hamlin said.

It’s possible that sales could increase now that two of Ohio’s 39 licensed processors will be distributing other forms of marijuana such as oils, lotions and edibles.

Sales could potentially increase even more if more patients are allowed into the program.

The state Medical Board told the committee it is evaluating 6 additional conditions based on petitions for consideration.

Executive Director A.J. Groeber said they have multiple experts examining the research for each condition, which include anxiety, depression, autism and opioid addiction.

The program has 24,556 registered patients, and that could expand if the Medical Board approves any of these conditions when it votes before a July deadline.

Managing Marijuana

Ohio’s program has so far limited patient access to medical marijuana because fewer than half of the state’s 56 licensed dispensaries are open right now.

As the Medical Marijuana Patient and Caregiver Liason for the state’s Board of Pharmacy, Grant Miller is charged with helping patients navigate the program.

“That includes working with patients and caregivers to go through the registration process,” Miller said. “We help them understand how the purchasing of medical marijuana works. And also help physicians and dispensary employees with questions should they encounter a situation they haven’t been briefed on.”

The state created multiple platforms patients can use to get answers, including online and the program’s toll-free hotline (1-833-4OH-MMCP).

The Board of Pharmacy is responsible for making sure dispensaries are meeting the state’s requirements.

Miller said they’ve developed a relationship with dispensary owners to help more of them get operational approval.

“There’s a lot that goes into the process of issuing a certificate of operation,” he said. “But at its core, it’s about the licensee showing the board that they have fulfilled everything that they said they would be doing in their application.’

That includes security, local zoning, and training employees to use the Ohio Automated Rx Reporting System.

The Harvest dispensary in Athens, Ohio, is still working with the board of pharmacy to get operation approval.

Harvest Health and Recreation, Inc. is an Arizona-based, vertically-integrated cannabis company with operations in 16 states. Public Affairs Director Ben Kimbro said the process in Ohio is similar to other states where the company set up shop.

“This is a medical product. By necessity it has to be regulated.”

Kimbro said he was converted to a believer in medical marijuana after personally witnessing the medical benefits and decided to get into the industry so that others could too.

Once Harvest receives final approval, it will offer registered patients a variety of cannabis products, consultation for different conditions, and general education about medical cannabis.

As a publicly-traded company, Harvest promotes itself as an economic partner to the community.

“It’s just a really special time to be involved in growing the markets, educating patients, getting to work with lawmakers,” Kimbro said.

Growing Concerns

The Harvest corporation, under the Harvest Grows LLC banner, was also awarded a level one cultivator license for a facility in nearby Lawrence County, Ohio. This designation allows the company to grow cannabis in a facility with a maximum of 25,000 square feet.

A company in Meigs County, Agri-Med Ohio LLC, also applied for a level one cultivation license but was only awarded a level two license, which allows for just 3,000 square feet.

To Randy Smith, this means fewer jobs.

“Locally, the impact has been very anticlimactic,” he said. “It’s just not what we hoped it would be.”

Applicants competed for 29 cultivation licenses — 16 of which are level one — with most being awarded to more populated metro areas.

Smith’s disappointed the state didn’t give more consideration to places like Meigs County that could use these jobs to replace ones lost to coal’s decline.

He hopes the state will someday add more licenses and they’ll be ready to fight for the opportunity if that days comes.

“A chance, a fighting chance. There’s too many good people in this part of the state and that’s all we need,” Smith said.

The WOUB News Team contributed to this story.