News

Small Towns Fear They Are Unprepared For Future Climate-Driven Flooding

By: Rebecca Hersher | NPR

Posted on:

It technically began last fall when Hurricane Florence swelled the Ohio River, but really it was all the unnamed storms that came after her — one after another after another, bringing rain on rain on rain across the central U.S. until the Mississippi River hit flood stage this winter.

It was the most prolonged, widespread flood fight in U.S. history. The entire Mississippi River basin — an area that drains about 40 percent of the continental United States — was at flood stage this spring for the first time in recorded history, according to the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers.

For those who were elected to lead their communities through hard times it was, frankly, exhausting.

Now, as the water recedes for the first time in months, a group of mayors from small and midsize towns along the Mississippi River are calling for more federal support to upgrade infrastructure and help move residents out of harm’s way.

A bipartisan House bill put forward this week by representatives from Minnesota and Illinois would set aside more federal money for low-interest loans that could be used protect against future floods.

Many leaders of riverfront towns support the proposal because while the flood defenses in major cities largely performed well in this spring’s deluge, many smaller communities were overwhelmed.

Downtown Davenport, Iowa, was underwater this spring after a temporary sand-filled flood barrier broke, and neighborhoods in Greenville, Miss.; Sioux Falls, S.D.; Pike County, Mo.; Fort Smith, Ark.; and the Pine Ridge Reservation in South Dakota were inundated. Up and down the Mississippi and its tributaries, residents and local emergency responders spent weeks filling sandbags as a last-ditch effort to protect lives and property.

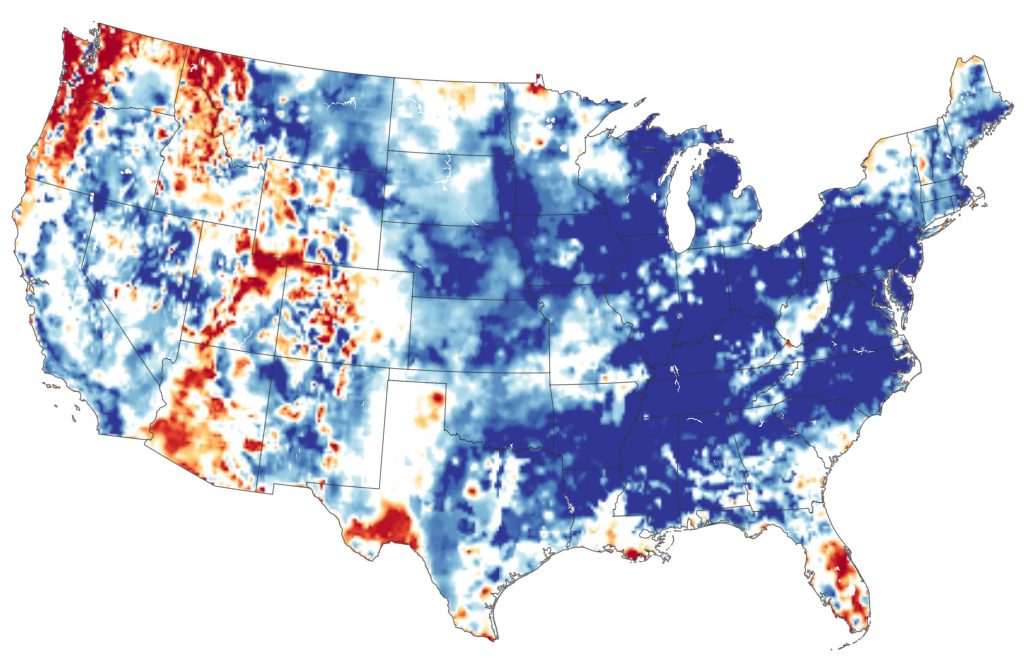

That has local emergency planners concerned about the future. Climate scientists warn that as the Earth gets hotter, more rain is falling in shorter periods of time across the Mississippi River basin. The 12-month period that ended in May was the wettest ever recorded in the United States. In the future, more extreme precipitation will likely mean higher rivers for longer periods.

In an April opinion piece published by USA Today, the mayors of Davenport, Minneapolis and Baton Rouge argued that the location and design of current infrastructure offers insufficient protection against the effects of a warming Earth. “Our broken river infrastructure is no match for what scientists predict is the new normal,” they wrote. “We should not have to depend on sandbags. Not in America.”

“It’s a quality of life issue.”

In Greenville, the Mississippi River dropped below flood stage this week for the first time since February. The city’s mayor, Errick Simmons, was part of a group of mayors who traveled to Washington, D.C., this week to ask the federal government for a revolving loan fund to help communities prepare for future floods

“We have had the longest record period of flooding ever – over 141 days,” Simmons says. In some places, the water came under levees that were inadequate to hold the river back for so many months on end.

“That long-standing water has resulted in major damage,” he says, including dozens of collapsed streets, about 100 buildings damaged or destroyed by water and thousands of residents affected by sewer pump failures.

Poorer residents are affected most seriously by the flooding and sewer failures. About 35 percent of Greenville’s residents live in poverty, according to the most recent U.S. Census data.

Simmons says the city has spent weeks struggling to fix the problem because the water level underground is so high that when crews dig down to repair sewage pumps, for example, they hit water, in some cases just a couple feet below the surface.

This year’s flooding might be the most prolonged, but it’s just the latest in a string of floods that have exacerbated existing infrastructure problems in Greenville. The city also dealt with damaging water in 2011 and 2016.

Mayor Simmons says he’d like to make Greenville more resilient to the floods he knows are coming, by upgrading the sewage and road infrastructure and by helping people who are currently living in low-lying areas — especially those who feel they can’t afford flood insurance — move to higher ground.

These are exactly the types of policy interventions that the federal government recommends for cities dealing with the effects of climate change. But Simmons says the city can’t afford it on its own, and the current federal grants that are available aren’t enough.

“The only way you can do something about this aging infrastructure is if you get federal help,” he says. Otherwise, “the only tools we have [are] to increase property taxes on people who are already impoverished, or have a regressive tax like [raising] sewer rates to fix the aging infrastructure.”

Paying for resilience

The underlying issue, flood experts say, is that so many Americans live in harm’s way. Millions of Americans currently live in flood-prone areas, either by necessity, preference, policy or a combination of all three, and climate change is exacerbating their risk.

“Stronger floodplain regulations are critical,” says Laura Lightbody, the head of the flood-prepared communities initiative at The Pew Charitable Trusts. “More things, assets and people in harm’s way means greater impact, costs and lives lost.”

Many local and state governments continue to allow, and even encourage, development in flood-prone areas despite that growing flood risk. In an opinion piece published last year in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, river engineer Desiree Tullos wrote that there are currently “perverse incentives for occupation of flood-prone areas along with a widespread lack of awareness of the associated risks.”

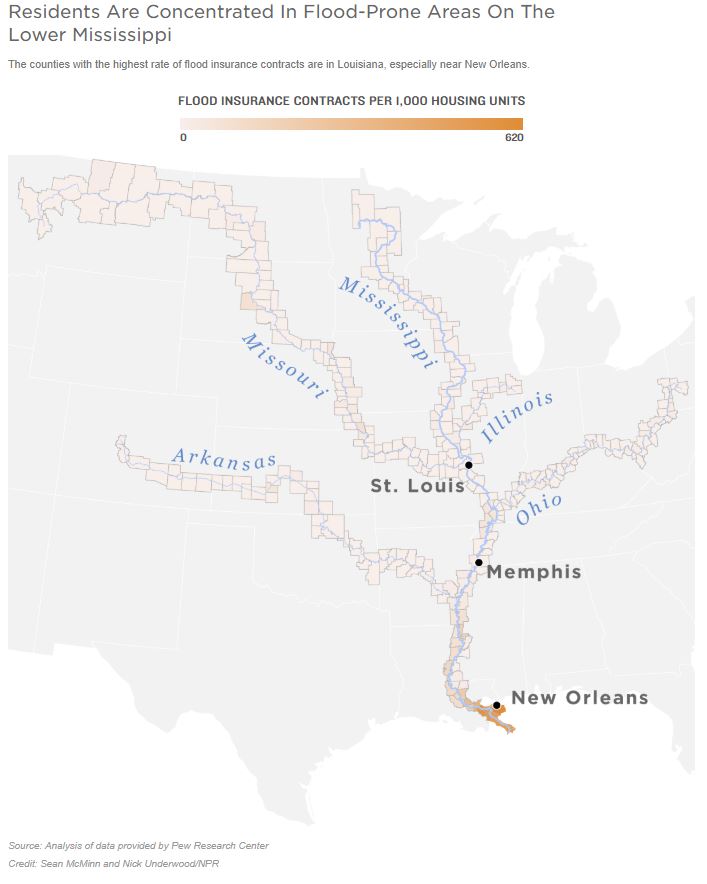

Along the Mississippi River and its tributaries, some places are more heavily populated than others. Flood insurance data offers one rough indication of where residents are concentrated in flood-prone areas, in part because those who reside in the floodplain and have a mortgage are required to buy insurance.

An analysis by Pew of recent flood insurance policy data from the Federal Emergency Management Agency showed that the highest rate of flood insurance contracts are in counties around the mouth of the Mississippi.

Don’t see the graphic above? Click here.

Many of the most densely populated flood-prone areas are in southeast Louisiana, including New Orleans. But while New Orleans residents are somewhat protected by billions of dollars of levees and other infrastructure, many smaller communities are not.

In Ascension Parish, La., which is located along the Mississippi River near Baton Rouge, the local government warns that the entire area is susceptible to flooding. Nonetheless, the population in the county has steadily grown over the past two decades even as flooding has gotten more severe. The area was badly damaged by flooding in 2016, and it was threatened again this year.

Curtailing development in flood-prone areas has helped other communities mitigate the damage from high water.

Tulsa, Okla., for example, has implemented stringent rules about where and how homes and buildings are constructed, as Joe Wertz of Oklahoma Public Radio has reported. Parts of the city flooded this year as the Arkansas River rose, but years of restrictions on building in the floodplain likely prevented more damage.

After a series of floods in Iowa, local officials worked with the Army Corps of Engineers to move levees farther from the river, making more room for the water and effectively limiting development in the most flood-prone areas. In Illinois, the state and federal governments have spent millions of dollars moving people out of flood-prone areas since the Great Flood of 1993.

But even in places lauded for their relatively strong flood-control policies, local leaders are worried that they are still under-equipped to handle the kinds of prolonged, record-breaking floods that battered them this year and are more likely in the future.

“Since 1993, we’ve moved residents out of the floodplain and other repetitive-loss areas,” Rick Eberlin, the mayor of Grafton, Ill., said during a call with reporters this week. But his riverfront town north of St. Louis is still susceptible to damaging floods. Roads were underwater this spring when the Mississippi rose to its second-highest crest ever.

Eberlin is among the local leaders calling on the federal government to make more money available for smaller towns like his to pursue flood mitigation projects, specifically the types of infrastructure upgrades that make room for the river and further disincentivize development in the most flood-prone areas. That includes restoring wetlands and moving levees back from the river’s edge.

“We are a smaller city,” Eberlin says. “We’re asking for a helping hand.”

9(MDI4ODU1ODA1MDE0ODA3MTMyMDY2MTJiNQ000))