News

Blackjewel Miners Continue Protest As Bankruptcy Hearing Looms

By: Brittany Patterson | Sydney Boles | Ohio Valley ReSource

Posted on:

Miners left unpaid by the bankrupt Blackjewel coal company say they are prepared to keep up their protest on railroad tracks in Harlan County, Kentucky, where they are blocking delivery of a load of coal. As their protest grows and gains attention, a bankruptcy court hearing on Monday could determine whether and when the miners get their paychecks.

The blockade began simply enough Monday when five out-of-work miners organized via social media to block a coal train leaving one of the Blackjewel facilities.

“If they can move that train, they can get us our money,” miner Shane Smith said.

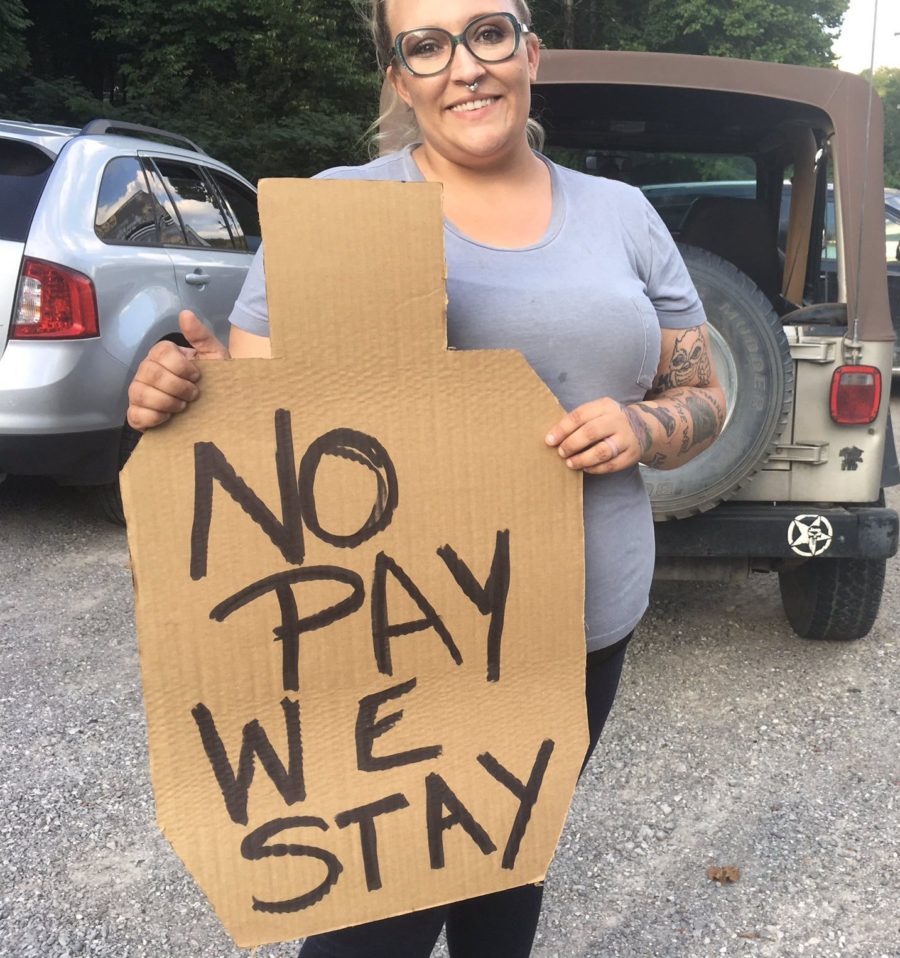

“No Pay, We Stay.”

The protest has since grown to dozens of miners and supporters, attracted national media attention, and has become a required pilgrimage site for campaigning politicians.

“It’s a little bit of a good feeling of accomplishment but we still ain’t done,” said miner Bobby Sexton. “We’re gonna stay here until we get some answers.”

But the miners are not the only ones looking for answers – and money – from what was the country’s sixth-largest coal mining company. A federal bankruptcy judge will decide who gets their money, and when.

Growing Protest

Blackjewel workers have gone without pay since the end of June, when, miners said, paychecks bounced without warning amid a chaotic bankruptcy filing. Backjewel owes more than $11 million in unpaid wages and taxes to roughly 1,100 workers in Kentucky, Virginia, and West Virginia.

But the company also owes tens of millions of dollars in business debts, taxes, mining royalties, and fines for mine safety and land reclamation violations.

During the course of the bankruptcy, federal Judge Frank Volk has expressed sympathy for Blackjewel employees, but has not yet forced the company creditors to pay them.

“The court is concerned about the employees,” Volk said during a July 19 hearing. “Where do they fall in the scheme in respect to recoveries in this case?”

That may become more clear Monday when Volk presides over a sale hearing. Blackjewel’s assets hit the auction block Thursday, Aug. 1. The closed-door process continued Friday.

Looming Decision

Sam Petsonk, an attorney with West Virginia’s Mountain State Justice, is representing miners from Backjewel’s eastern division. He said whether or not miners get paid depends on how much money comes from the sale of Blackjewel’s assets.

“What we need to see out of the auction is adequate proceeds to cover the obligations to the employees who are not returning to work,” he said.

Employee wage claims generally do have some priority in bankruptcy cases, but come below “secured” claims and obligations to the government such as mine reclamation costs, Petsonk said.

He is hopeful unpaid Kentucky miners may be near the top of the list of creditors due to a state law that requires some Kentucky employers to post a performance bond covering wages. Blackjewel didn’t comply with that law.

On Friday Beshear called on Bevin to fire his Labor Cabinet Secretary over the matter.

“His job is to look out for our workers, but he failed to secure the bond from Blackjewel that could have paid the coal miners in Harlan County,” Beshear said at an event in Paducah, Kentucky.

Petsonk said if the proceeds of the sale are not sufficient to pay miners, it could then come from liquidating the company’s remaining assets.

If that isn’t enough, he said, “then we have to look to the we have to look to the liquidation process or to the non-debtor entities like Jeff Hoops personally.”

Hoops is the former Blackjewel CEO who was forced out early in the bankruptcy, when creditors demanded he step down. Hoops is well-known for his philanthropy in the area and is building a resort hotel near his home in Milton, West Virginia. He also has a separate coal entity, Lexington Coal Company.

Reached by phone Tuesday, Hoops said he’s also frustrated by the situation with the unpaid miners.

“I’m as frustrated as they are,” he said. “I no longer work for Blackjewel, I resigned more than a month ago so I have no idea what’s going on there. I’m really sorry that it’s reached this point.”

“A Real Mess”

Hoops has been the focus of ire for many of the protesting miners, and his name shows up in some unflattering T-shirt slogans. Some industry observers say the company’s management under Hoops’ leadership set the stage for the chaotic bankruptcy and its aftermath.

“Let’s be clear about this,” said Clark Williams-Derry, director of energy finance at the Sightline Institute, a Seattle-based think tank. “Blackjewel was a company that suffered from terrible financial management, just terrible.”

He said the company wasn’t setting aside enough money to pay wages or make its employee retirement plan contributions. And Blackjewel amassed huge debts in back taxes to the federal government and to state and local governments.

“It’s just a mess, just a real mess,” Williams-Derry said.

“Some of these mines are probably just not profitable,” Williams-Derry said, especially those carrying large debts for mine land reclamation. “There may simply be no buyer who’s willing to take on some of these mines and and pick up the cost of cleanup.”

The miners in Harlan County say many plan to attend the court hearing Monday to make sure their voices are heard.