News

Ohio University Leaders Struggled To Forecast Depth Of Budget Crisis

By: David Forster

Posted on:

Editor’s note: This is the first in a series of stories that will examine the budget crisis that has left Ohio University looking to cut millions of dollars in expenses. As the region’s largest employer, the decisions it makes can have a profound effect on the local economy. The stories will look at the specific issues facing Ohio University but also attempt to put them into the broader context of the challenges facing higher education throughout Ohio and the rest of the country.

ATHENS, Ohio (WOUB) — In June 2019, Ohio University’s board of trustees was presented with a long-term budget projection that had a gloomy start but a happy ending.

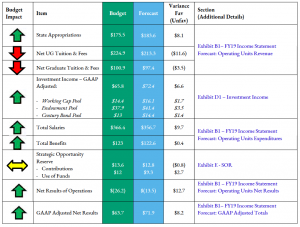

It showed that the university would burn through nearly $66 million in reserves over the next four years to cover deficits largely caused by declining enrollment. But this would be followed by a modest recovery.

Four months later, the board was presented with a revised forecast: There would be no recovery in the next six years and the university would need to draw more than $129 million from reserves to cover the deficits.

This was just the latest in a long line of revisions to what turned out to be overly optimistic budget projections as university leaders struggled to adjust after years of record-breaking enrollment came to an abrupt end.

Ohio University’s financial situation is even more desperate now as the coronavirus pandemic takes a heavy economic toll. But the pandemic has simply laid bare and accelerated trends that were already well underway.

Even without the pandemic, the university was heading for a serious financial reckoning. And its leaders were still struggling to develop realistic projections when the virus came along and added a huge dose of uncertainty and extra costs.

The university has already eliminated more than 400 positions, mostly through layoffs, and imposed mandatory furloughs on remaining employees to cut costs. But it doesn’t even come close to closing the budget gap.

The latest projections, presented to the board in October, show that more than $290 million would need to be drawn from reserves to cover the deficits between now and fiscal year 2025.

But that’s not going to happen. The board of trustees and university leaders have made it clear that significant cuts will need to be made instead.

How did it come to this?

To answer this question, WOUB News reviewed the agenda materials and minutes of board meetings going back four years. This revealed how university officials struggled to make reliable enrollment projections, and therefore reliable financial projections, that could stand for even a few months before they needed revision.

It also showed that all the enrollment strategies presented to the board over the past several years proved unsuccessful in reversing or simply stopping the decline as the university competed for students in an increasingly competitive market.

At the tipping point

Just four years ago, the picture looked a lot different. The 2016-17 school year marked the 10th year of record-breaking enrollment at Ohio University. It also turned out to be the last.

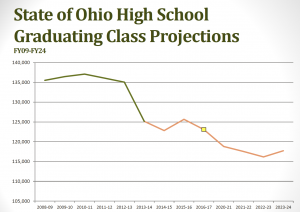

By this time, leaders at Ohio University and other universities in the state were already aware of a disturbing trend: The number of high school graduates in Ohio was declining sharply and was expected to continue to decline. This is a national trend, but the decline in Ohio has been much steeper than the national average.

This presented a serious challenge for Ohio University, which draws the vast majority of its student body from within the state.

At the October 2016 board of trustees meeting, trustee David Pidwell asked if the upward trend in enrollment would continue or if the market was shrinking.

Craig Cornell, the university’s senior vice provost for strategic enrollment management at the time, said that continued enrollment growth on the Athens campus was limited primarily by housing and other physical constraints. He said the key to continued enrollment growth was likely through online programs.

Pidwell also noted that the university’s out-of-state enrollment was declining and asked why this was happening. Cornell said there was stiff competition for out-of-state students and that many universities were marketing heavily toward these students, who pay much higher tuition.

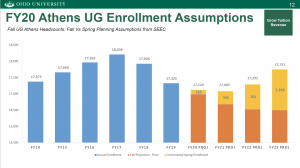

In January 2017, the board was presented with enrollment projections for the 2017-18 school year. University leaders were projecting that the years of steady enrollment growth would continue, with yet another gain in undergraduate enrollment on the Athens campus.

Trustee Dave Scholl asked if the projections were based on conservative estimates, and he cautioned that the university should not get too aggressive with its expectations. This is a theme Scholl and other trustees would come back to again and again at board meetings as one projection after another proved too optimistic.

Deb Shaffer, the university’s senior vice president for finance and administration, assured Scholl the projections were based on the same enrollment rate equation used in previous years, working with a five-year average.

A financial squeeze

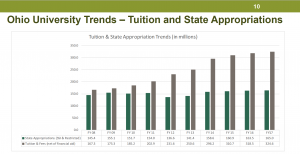

Meanwhile, the university was facing some new financial pressures. Its share of the state dollars allocated to universities had flattened despite the historic enrollment gains. This was due in part to a change in the allocation formula.

The state imposed a two-year freeze on in-state undergraduate tuition increases starting with the 2017-18 school year. This meant the university could not simply raise tuition to help offset any revenue declines.

Plus, the university was now working under self-imposed tuition constraints with the recent adoption of a tuition guarantee program, which was a new recruitment tool. Students who enroll under the voluntary program are guaranteed that their tuition will not be raised for four years.

The university was also spending more each year on financial aid as it competed more aggressively for students. These increases in financial aid awards were offsetting some of the increased tuition revenue from the record enrollments.

These and other financial pressures left university leaders increasingly boxed in as far as adjusting to any declines in revenue or increases in expenses, including the tens of millions of dollars in debt the university was accumulating as it borrowed to build new buildings and renovate others.

Start of the slide

Early in 2017, university leaders were planning for flat revenue growth for the coming school year. But two months before the start of the fall 2017 semester, Shaffer told the board that the revenue projections were off and the university was now facing a projected $15 million deficit that would be plugged by drawing from reserves.

Part of the reason for this is that the January projections for a slight increase in enrollment for the coming school year had now turned into a projected decrease.

The university was also facing a new enrollment challenge. Donald Trump had taken office as president in January with a pledge to crack down on immigration. His administration immediately began adopting restrictive immigration policies, including a ban on immigration from several Muslim countries. This was coupled with an overall hostile tone toward immigrants in general.

University leaders told the board that these policies were contributing to a decline in international students, who pay the highest tuition. Many of them were opting to go to universities in Canada instead.

Still, university leadership sought to put a positive spin on the latest projections. Pam Benoit, then executive vice president and provost, told the board that while enrollment would be down, it would still be the third-highest in the history of the university.

Trustee Victor Goodman remarked that in the context of record enrollment gains over the past decade, a slight dip in enrollment was not cause for concern.

By the time the fall 2017 semester got underway, university leaders had again revised downward the projected enrollment, with a corresponding $500,000 loss in revenue.

Cornell, the enrollment provost, said the university was facing increased competition from peer institutions and concern from families about affordability. He said the university was making a push to recruit more international students, with an initial focus on China.

Not conservative enough

2018 started out much the same as 2017, with university leaders again projecting a slight increase in enrollment for the next school year.

This again had a trustee asking if the enrollment targets were conservative enough. Another trustee questioned whether the university should continue to pursue record-breaking enrollment or instead decide how big it wants to be and aim for that.

University leaders presented the board with an enrollment plan that projected the Athens campus leveling off at around 17,700 students and then trying to maintain that level through scholarships, more out-of-state and international students, and improved retention rates that led to more students completing their degrees.

But there would be no leveling off. Instead, enrollment has declined at a steady clip year after year, a trend that is expected to continue. The projections showed just how hard it was for budget planners to come down from the highs of the good years.

The rest of 2018 played out much the same as the year before. By midyear, university leaders told the board that instead of a small bump in enrollment, they were now projecting it would be even less than the year before.

The enrollment declines were happening in almost all categories: first-time freshmen, transfer students, online students, graduate students. The declines were most pronounced on the university’s regional campuses, but the Athens campus was also seeing a drop in enrollment.

The loss in tuition revenue combined with other revenue shortfalls would require drawing several millions dollars more from reserves to plug the deficit.

Shaffer told the board the university needed to get a better read on determining the right number of students to plan for in future budgets.

As the fall 2018 semester got underway, Cornell told the board it was now clear that enrollment had peaked two years ago and the university was facing a gradual decline.

The board made it clear that moving forward, the budgets needed to be built on even more conservative modeling.

Down, then down again

In January 2019, university leaders presented the board with enrollment projections that acknowledged the decline but saw it as a temporary setback. Enrollment would continue to drop for two years, but this would be followed by two years of increases, with a significant increase in the fourth year. Board members were told this growth would come from new initiatives that would boost in-state, out-of-state and international enrollment.

Meanwhile, the combination of declining enrollment, no tuition increases, increased financial aid spending to recruit students and little change in state funding meant the university might have to dip even deeper into its reserves to plug the deficit.

By the start of the fall 2019 semester, it was clear that even the more conservative enrollment forecasts were still too optimistic. In August, the board was told that the enrollment shortfall translated to $3.5 million in lost revenue. Just two months later, the board learned it was even worse. Enrollment was lower than estimated in the August revision, adding another $3 million to the tuition shortfall.

This enrollment decline not only blew a hole in the current budget but also forced a revision to the multiyear projections that had been presented to the board a few months earlier at its June meeting.

The original projections showed a nearly $66 million draw from reserves to cover deficits for a few years, with a recovery beginning in fiscal year 2024. Now, based on what were considered more realistic enrollment projections, no recovery was expected over the next several years, and the university would draw more than $129 million from reserves to cover deficits through fiscal year 2025.

University leaders told the board they planned to address this bleak forecast with initiatives to boost enrollment, including more targeted recruitment efforts in major cities outside Ohio, new financial aid strategies, new online programs and new credential programs for adults in the workforce.

The board did get some good news heading into the 2020 fiscal year.

The state was increasing its financial support to universities, with Ohio University set to receive several million dollars more than expected. Also, the latest state budget permitted a small increase in tuition.

Unfortunately, in just a few months both of these expected financial gains would be eliminated by the coronavirus.

Cuts, and more cuts

By the time 2020 got underway, university leaders had spent three years cutting costs here and there, shaving millions of dollars in expenses to meet the increasingly grim projections. On the revenue side, tuition and fees were raised where allowed under state law. Room and board rates were increased.

But it wasn’t enough to close the growing budget gap.

Employees are by far the university’s biggest expense. In fall 2019, the university leaders eliminated vacant positions, saving millions of dollars that would have been spent on wages.

And at its January 2020 meeting, the board approved a plan to encourage some current employees to leave: The university would offer early retirement incentives to tenured faculty and unionized custodial staff.

Two months later the campus shut down after spring break in response to the coronavirus pandemic.

As the pandemic battered the state budget, the governor slashed state funding to universities. Instead of getting millions of dollars more than expected, Ohio University would now be getting significantly less.

A week before the May board meeting, the university laid off 140 union employees, including custodial, culinary and maintenance staff.

Elizabeth Sayrs, the university’s executive vice president and provost, told the board in May that enrollments do not support the current level of academic or administrative staff and that the university must resize to remain sustainable. She said that no part of campus would be unaffected by the cuts.

In response to the pandemic, the board voted to not increase undergraduate tuition or room and board rates for the coming school year. This decision has a compounding effect on the budget because students who enrolled this fall under the guarantee program cannot have their tuition raised.

Shaffer told the board that the university would need to draw around $50 million from reserves to close out the 2020 fiscal year at the end of June. And it was projecting a $56 million draw in the coming fiscal year.

President Duane Nellis said the university needed to act quickly to avoid depleting its reserves. He expected bigger drops in enrollment as high school graduates took a gap year or decided to go to a college closer to home because of the pandemic. He said current students might not come back for a year or might not return at all.

Two more rounds of layoffs followed the May meeting, totaling 283 employees, although some of them were rehired into other positions.

Still not enough

University employees are now bracing for more cuts certain to come. It’s just a question of when. Nellis said at the May meeting that all the actions taken so far were still not enough to address the shortfalls the university is facing.

At its August retreat to discuss the budget crisis, the board was presented with a new multiyear projection. It was based in part on enrollment projections that university leaders hoped were finally conservative enough that they could stand for more than a few months and serve as a reliable basis for budgeting.

The projections showed an estimated $25 million draw from reserves for the current fiscal year and $60 million or more annually starting next fiscal year.

Trustee Dave Scholl noted that the projected revenue over the next several years had dropped significantly from the previous multiyear projections, but there hasn’t been a corresponding decrease in expenditures.

This is not sustainable, he said. The university cannot continue to plug its deficits with reserves as it drains its reserve pool. He said the university needed a significant increase in enrollment or a big cut in costs.

The former doesn’t seem likely.

Ohio University holds WOUB Public Media’s license to operate.