News

Ohio University’s Budget Crisis Rooted In Economics Of Higher Education

By: David Forster

Posted on:

Editor’s note: This is the second in a series of stories examining the budget crisis that has left Ohio University looking to cut millions of dollars in expenses. As the region’s largest employer, the decisions it makes can have a profound effect on the local economy. The stories look at the specific issues facing Ohio University but also attempt to put them into the broader context of the challenges facing higher education throughout Ohio and the rest of the country.

ATHENS, Ohio (WOUB) — As Ohio University deals with a growing budget crisis, it may find itself caught in what could be a vicious cycle.

It goes like this: As enrollment declines and the university competes for a shrinking pool of students, it spends more on financial aid.

This aid is offered as an enticement to get students to come and stay until they graduate. But it also means less revenue. If a university charges $15,000 for tuition but offers a student a $5,000 scholarship, it’s net tuition revenue is $10,000.

This aid is offered as an enticement to get students to come and stay until they graduate. But it also means less revenue. If a university charges $15,000 for tuition but offers a student a $5,000 scholarship, it’s net tuition revenue is $10,000.

Tuition is the university’s main source of income, and it’s already facing serious revenue shortfalls. So to boost revenue, it raises tuition and competes even more aggressively for students.

But higher tuition and more competition lead to more spending on financial aid to make the university more affordable and attractive. So the gains in tuition revenue are again partially offset by the increased spending on financial aid.

And so the cycle goes.

There are signs that Ohio University is already slipping into this cycle. It would be far from alone. Universities around the country are caught up in the same cycle to a greater or lesser degree.

Let’s make a deal

This cycle has its roots in the economics of higher education.

For one thing, there are a lot of colleges in the United States, and it’s difficult for prospective students to determine just how good one is relative to another.

The most elite universities have reputations that precede them. But for the rest, students often end up turning to things that have become signals for quality but may in fact have little to do with the actual value of a student’s educational experience.

One signal is cost. Companies discovered long ago that consumers often associate high cost with quality. This consumer psychology has led private colleges in particular to adopt a high-cost, high-aid economic model.

Under this model, colleges inflate their tuition rates, which they hope prospective students will see as a measure of quality. The colleges then offset their sticker price with a lot of financial aid to get the students they want.

There’s another psychology at work here. While the high tuition can make the colleges look good, the financial aid awards can make the prospective students feel good. The students feel like they’re getting a deal. And when the award is based on merit rather than financial need, it sends a signal that the students have earned it on the strength of their own qualifications. It’s a reward.

Matt DeMonbrun said it’s like shopping for a car. DeMonbrun is associate director of the Office of Institutional Research at Southern Methodist University, where he researches and writes about enrollment management practices.

“You show up at the dealership and the salesperson comes and talks to you and says, ‘You see the MSRP, right? That’s the sticker price. … (But) you know what, you’re a really great person. We know you’ve got great credit. You’re not going to pay that amount. Here’s the deal I’m going to give you.”

The trick with this kind of tuition discounting is offering just the right amount of financial aid for each student to seal the deal. For some students, a little is enough, and the higher tuition they pay helps subsidize the lower tuition paid by students who receive higher amounts of financial aid.

“They call these cocktail scholarships, where you could imagine parents at a cocktail party bragging about their kid who got a scholarship to go to some college,” said Nick Hillman, a professor of education and expert on higher education finance at the University of Wisconsin-Madison.

“It’s not that the kid is a phenomenon, but the colleges know they can just throw a little bit of money at a lot of students and that might be enough to induce that student to want to go to their college as opposed to some other place.”

But not too much

Tuition discounting requires a delicate balancing act. Universities cannot set tuition so high that they price themselves out of competition, despite the financial aid. And they cannot offer so much financial aid to get the number of students they need that the net tuition revenue isn’t enough to cover their expenses.

Private universities have decades of experience with tuition discounting. But that doesn’t mean they can’t run into trouble, especially as they are forced to compete more aggressively for students.

The ratio of financial aid to gross tuition is what is known as the discount rate. The higher the discount rate, the more money is being spent on aid relative to the tuition sticker price and the lower the net tuition revenue.

Every year the National Association of College and University Business Officers publishes a report that includes the average discount rate for private universities. The rate has been climbing steadily in recent years, reaching new records year after year. In the latest report, the discount rate was 52.6 percent for first-time undergraduates and 47.6 percent for all undergraduates. What this means is that for each dollar a private university receives in tuition, it’s giving about 50 cents back in financial aid.

This growth in the discount rate is in part a reflection of flat or declining enrollment as colleges spend more on financial aid to fill seats.

The rising discount rate has experts concerned that as private universities offer more and more financial aid to hit their enrollment goals or at least slow the decline, revenue will fall increasingly short of expenses, forcing them to make cuts that could affect their academic quality or even forcing them out of business.

Public universities haven’t been discounting tuition to quite the same extent. But many of them have been taking a similar approach when it comes to raising tuition and financial aid awards.

For example, tuition for in-state students at Ohio University was $5,085 a year in 2000. It is now $12,612. That’s an increase of 148 percent, which is way above the rate of inflation, and the growth in wages, over the past 20 years.

If tuition had simply tracked the consumer price index, which reflects the growth in prices of a broad range of consumer goods and services, in-state tuition today at Ohio University would be around $7,600. This is according to an inflation calculator provided by the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics.

Tuition for out-of-state students also more than doubled over the same period, from $10,704 in 2000 to $22,406 today.

Most incoming students do not actually pay the sticker price, however, because of grants and scholarships they receive from the state and federal government and from the university, along with tuition discounts.

Just like tuition, the amount of financial aid Ohio University offers has grown significantly. This growth can be tracked through the annual reports the university files using Common Data Set, which is a standardized data reporting method used by colleges nationwide.

The report for the 2002-03 school year shows the university offered $11.8 million in financial aid, including grants, scholarships and tuition discounts. This amount has grown steadily over the years, and by the 2019-20 school year it had more than quadrupled, to nearly $50 million.

The majority of this aid is awarded based on financial need, a determination based in large part on a family’s income and other financial resources.

But a significant chunk of the financial aid awarded is not based on need. These are often referred to as merit awards because they are based on things such as a student’s high school GPA or scores on standardized tests such as the SAT or ACT.

In the 2019-20 school year, $15.2 million in financial aid, or close to one-third of the nearly $50 million total awarded, was not based on need.

Making the lists

Universities offer financial aid to students who may have little or no financial need in order to recruit a certain mix of students. And this leads to another proxy for academic quality that is helping drive the increases in financial aid: college rankings.

Like high tuition, rankings can be a crude measure of how good a university actually is. But the rankings, especially those produced by U.S. News & World Report, are widely used and widely cited.

“When you have a product in the marketplace that people don’t really know how to gauge its quality, then any of these measures can sort of be proxies for quality even though they’re really bad proxies,” Hillman said.

Colleges may not like the rankings, which tend to treat education like any other commodity, but they understand how influential the rankings are and routinely sift through them to find something they can use as bragging rights in their own marketing. University marketing departments routinely fire off news releases touting their latest ranking in one list or another.

Ohio University lists several rankings on its home page to impress prospective students, including a recent U.S. News & World Report ranking that named the university No. 1 in best value among public universities in Ohio. This ranking is based in part on the percentage of students receiving scholarships and tuition discounts, so it rewards schools that are sacrificing revenue for enrollment.

The most prestigious rankings are based on a number of variables, but significant among them are the academic qualifications of the student body, including GPAs and performance on standardized tests.

This leads to greater competition among universities for these high-achieving students, who will help drive up their rankings, and this competition often comes in the form of generous scholarships and tuition discounts.

Ohio University’s 2017-23 Strategic Enrollment Management Plan, a six-year blueprint for enrollment goals, makes it clear that targeting high-achieving students is a priority. The plan notes that academic quality indicators at the Athens campus “have grown steadily and reached new milestones” and says the university will leverage financial aid to continue nudging up the average GPAs and ACT scores of its incoming freshmen classes.

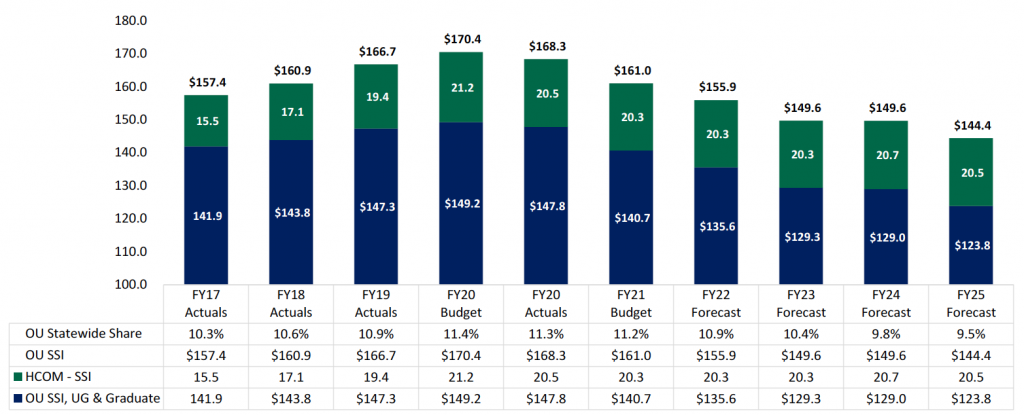

Rankings and bragging rights aside, there’s another reason public universities might spend heavily on financial aid for high-achieving students: State funding might be tied to student performance.

That’s the case in Ohio, where each state budget includes a certain amount of funding for higher education that gets divided up among the public colleges and universities. The amount that goes to each is determined primarily by the number of courses completed by students and the number of degrees earned.

This creates an incentive for universities to recruit students who are most likely to stay and graduate, and one measure of that is their performance in high school.

A long time coming

For years, even as the amount of financial aid awarded was swelling at Ohio University, net tuition revenue was climbing or holding steady, so there wasn’t much cause for concern. Part of this had to do with the steady increases in tuition rates, which helped balance out the increased spending on financial aid.

And part of it had to do with a long stretch of enrollment gains, including a decade-long run of record-breaking enrollment starting in fall 2006. More students means more overall tuition to offset the growth in financial aid.

Where universities run into problems with financial aid is when enrollment starts to decline and raising tuition is no longer a viable option or at least a more limited one. This can lead to a situation where they’re spending more on financial aid to get fewer students and the corresponding declines in net tuition revenue create budget deficits.

This is what’s happening at Ohio University and other universities around the state and the nation.

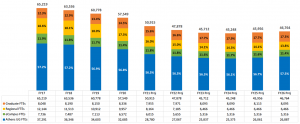

Enrollment at Ohio University peaked in the 2016-17 school year and has been declining since and is expected to continue to decline for at least a few more years.

The university knew this was coming.

“A lot of enrollment predictions had indicated that the Midwest was going to experience sharp declines in high school graduating classes around this time,” DeMonbrun said. “We’ve been saying this for years now that this was going to happen.”

This projected enrollment decline began several years ago, and in Ohio it has turned out to be much more severe than the average for Midwestern states.

Ohio University draws the bulk of its students from Ohio. The percentage of undergraduates who are Ohio residents has hovered around 85 percent for many years. The decline in high school graduates means that Ohio University is facing more competition for Ohio students.

The university’s six-year enrollment plan acknowledges that with a declining population of Ohio high school graduates, it will need to spend more money to meet its enrollment goals.

The plan also identifies the other schools in the state that Ohio University competes with most directly for students. High-achieving students who apply to Ohio University but end up going to another school most often end up at Ohio State University, Miami University or the University of Cincinnati. For lower-income and first-generation students, the top competitors are Kent State University, Bowling Green State University and the University of Akron.

And Ohio University is not just competing with other universities in Ohio for students, it’s increasingly competing with universities in other states.

Universities are always looking to recruit more out-of-state students because they pay more in tuition. But as the overall pool of high school graduates is shrinking, universities are more aggressively targeting out-of-state students to help offset the declines in in-state students and hold the line on enrollment.

Ohio University has taken steps over the past few years to recruit more students not only from other states but other countries, especially China. Despite these efforts, the number of out-of-state undergraduates has declined over the past several years and the overall balance of students has stayed about the same.

The coronavirus has made recruitment even harder as more students opt to attend a university closer to home, especially since so many of their classes are online anyway, or decide to take a year off from school and wait out the pandemic.

How much higher?

As net revenue drops in the face of enrollment declines and increased financial aid spending, universities can keep raising tuition to help offset the losses. But at some point, tuition simply becomes too high.

Even with the significant increase in financial aid spending over the years, Ohio University is meeting about 50 percent of the financial need of undergraduates who are awarded need-based aid, according to its most recent Common Data Set report.

And to help cover the rising costs of tuition and room and board, more students are borrowing and they’re borrowing more heavily.

Eighteen years ago, the average loan debt for an Ohio University graduate was a little over $15,000. Last year it was close to $29,000. And these are averages. Some students are borrowing less while others may be borrowing considerably more.

The concern is that “eventually we’re going to hit this point in time where people are going to say I just can’t do it anymore,” DeMonbrun said. “Higher education always had benefits, and yes I make X amount of money more than I would if I had a high school diploma, but I just can’t do it anymore.”

But even if Ohio University wanted to keep raising tuition to cover financial shortfalls, this is a much more limited option than it once was. Most of the big jump in tuition at Ohio University over the past two decades happened from 2000 to 2012, when it doubled. Since then, tuition has grown at a much slower pace.

Part of this has to do with restrictions by the state Legislature. Over the years, the Legislature has imposed caps on tuition to slow the growth. It has been tapping even harder on the brakes in recent years with more restrictive caps. For four years starting in fall 2015, no tuition increases were allowed.

Meanwhile, Ohio University has imposed its own restrictions on tuition growth. In 2015, it became the first public university in Ohio to offer students a tuition guarantee under which students pay the same tuition for four years.

The university can raise the tuition for each incoming freshman class, but these increases are still subject to the state tuition caps.

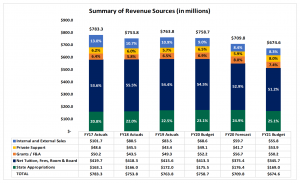

These limits on tuition growth come as the university has become increasingly more dependent on tuition revenue to pay the bills. Thirty years ago, the percentage of revenue that came from state funding and from tuition were about the same. In other words, the university relied pretty much equally on both to cover expenses.

This remained the case throughout the 1990s. But starting in the 2000s, they began to diverge sharply as enrollment and tuition rates rose, increasing tuition revenue, and state funding remained relatively flat. When state funding is adjusted for inflation, the real value of the annual appropriations has actually declined over the years.

Today more than half of the university’s revenue comes from tuition, including room and board, and less than a quarter comes from state funding. This has been the case for the past several years. And it means that the university’s financial health is more sensitive to shifts in enrollment.

This puts more pressure on the university to hold the line on enrollment, which can lead to more spending on financial aid to get students to come, which means less net tuition revenue, which can lead to budget deficits and create even more pressure to increase enrollment, and perhaps raise tuition to the extent that it can, to make up the shortfalls.

This is the vicious cycle.

A troubling sign?

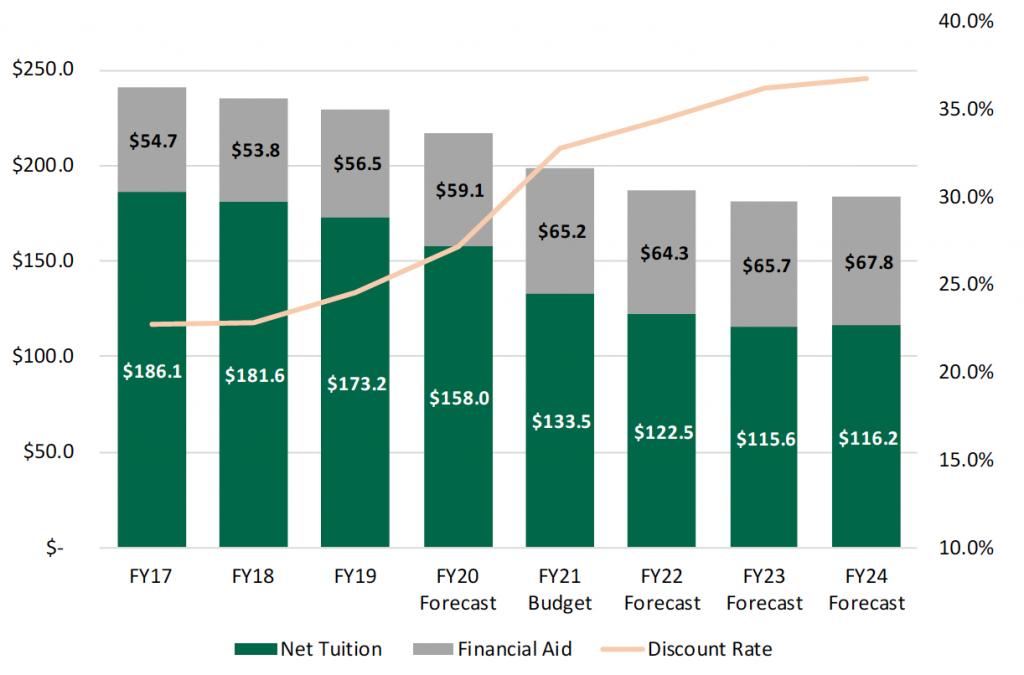

As enrollment declines and spending on financial aid goes up, Ohio University’s discount rate, the percentage ratio of financial aid to gross tuition revenue, is rising. The discount rate had already been creeping up even during the good years as the university spent more heavily on financial aid to recruit students.

But as enrollment began declining a few years ago and spending on financial aid continued to rise, the discount rate has been rising more rapidly. In the 2017-18 school year the discount rate was 22.7 percent. It rose to 24.3 percent the following year and to 26.7 percent the year after that.

The discount rate is expected to shoot up this year to 33.7 percent. This means that a third of tuition revenue will be offset by financial aid awards. Some of the big increase this year is tied to the coronavirus pandemic as the university doles out even more financial aid to recruit new students and encourage current students to stay.

Discount rates have been steadily rising at other public universities in Ohio, with executives at some of these schools expressing concern that the number is getting too high.

At Miami University, where tuition has risen faster and higher than at any other public university in Ohio, net tuition revenue has been dropping over the past few years as the university spends more on financial aid to shore up enrollment.

David Creamer, Miami’s vice president of finance and business services, told the university’s board of trustees at its September meeting that “the trend in revenue remains alarming and a concern for us.”

“It applies pressure to continually try to grow the size of the class since the amount of tuition that’s being generated per student is less each year,” he said.

In a financial update in October, the president of Kent State University noted that financial aid had grown 267 percent over the past decade and continues to grow as enrollment declines and the university raises tuition to increase revenue. He said his administration is working to reduce financial aid expenses.

Executives at Ohio University say they’re keeping an eye on the growing discount rate but are not too concerned yet. Candace Boeninger, the university’s interim vice provost for strategic enrollment management, said the recent spike in financial aid spending will ease somewhat after the pandemic has run its course.

But the university will still need to compete aggressively for students in the face of enrollment declines, and this may require that it continue to spend more on financial aid to net fewer students than in years past.

What if it went down?

One option for universities faced with rising discount rates and declining revenue is to lower tuition so they don’t have to shell out so much money in financial aid to offset the higher tuition costs.

A few universities have done this. But it’s a big gamble. It means bucking a higher education model that has been built on offering scholarships and tuition discounts as a recruitment tactic. The high-achieving students may expect to get something in return for all their hard work in high school, even if the university is already offering a lower tuition.

“If at the end of the day the net price will be the same, will you be more successful by having a lower sticker price and small or no aid or a higher sticker price and a higher scholarship? It’s a marketing issue and a psychological issue,” said Lucie Lapovsky, a national expert on higher education financing who runs a consulting practice advising universities on enrollment strategies.

The risk in lowering tuition is that the university ends up spending more on financial aid than it expected to get the students to come, while at the same time bringing in less revenue because of the tuition cut.

Another risk is that the lower tuition simply does not end up having the intended effect: It does not draw in enough extra students to make up for the tuition cut and the university winds up losing more money. This would be particularly painful at Ohio University because incoming students would be locked in at this lower tuition for four years.

Predicting enrollment is a tricky thing. Ohio University leadership did not expect the decline to be as sudden and as steep as it’s been, and so far every projection they have made over the past few years has proven too optimistic.

The alternative to raising revenue is cutting costs. And in the short-term at least, as university leaders work to get the budget back into balance, this seems the more likely path. The university has already eliminated more than 400 positions this year, mostly through layoffs, and imposed mandatory furloughs on remaining employees to cut costs, and more cuts are expected.

“Sometimes, guess what, you’re not making enough money to make the bills meet, so you have to find out ways to get rid of the bills,” DeMonbrun said. “And so, unfortunately, one of the easiest bills to get rid of are salaries and benefits.”

Ohio University holds WOUB Public Media’s license to operate.