News

Early retirement took off during the pandemic. An economic downturn could change that

By: Andrea Hsu | NPR

Posted on:

WASHINGTON, D.C. (NPR) — Before the pandemic, no one would have guessed that Dean Hebert was headed toward early retirement, least of all himself.

He was enjoying his job as an academic adviser at the University of Maryland Honors College. He imagined he’d work at least another five years.

Then in the pandemic, Hebert reconnected with a woman he’d known years earlier who lived in North Carolina. Remote work allowed the relationship to flourish. When the campus reopened, things got harder.

Fortunately, while working from home, he’d developed a new obsession: looking at retirement planners. He soon figured out that his frugal living and smart investments had paid off.

At the end of July, a few months shy of his 55th birthday, Hebert retired from his 28-year career at the university. He’s now getting ready to move to North Carolina.

“I had a choice between two really wonderful things and I just went with the one that seemed the better choice,” he says.

Financial security led older workers to retire

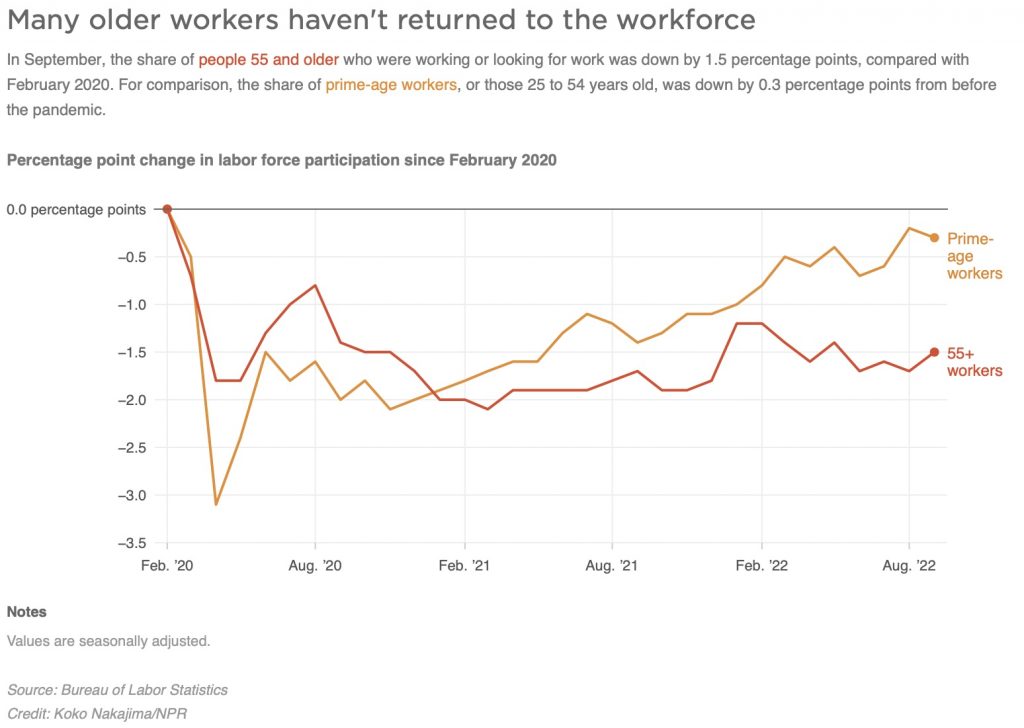

Even as many Americans have returned to work over the past year, making up for most of the pandemic losses in the labor force, a sizable number of older workers are choosing to remain on the sidelines.

In September, the share of people 55 and older who were working or looking for work was down 1.5 percentage points as compared with February 2020, according to the Labor Department. (For comparison, prime-age workers, or those 25 to 54 years old, are down just 0.3 percentage points from before the pandemic.)

There are a number of complex demographic factors contributing to that drop.

There are also reasons that are more easily explained. In the pandemic, many older workers had time to rethink their priorities. And until recent months, the pandemic had been good to them, financially.

“It just dawned on me at some point that there’s enough money there. If I worked for five more years, the only result of that would be I would die with more money in the bank,” Hebert says.

Lauren Bauer, a fellow in economic studies at the Brookings Institution, has found college-educated older workers in particular now have choices.

“One of the reasons that we saw older workers feel empowered to leave the labor market during COVID is that their balance sheets were fine,” she says.

Things were different for older workers after the Great Recession

Today’s situation is very unlike what happened after the Great Recession when the housing market crashed and many older workers couldn’t retire because they couldn’t afford to. For years, older workers stayed on the job, offsetting the decline of younger people in the workforce.

Now things are reversed. Older people, especially those over 65 choosing not to work is a big reason the workforce hasn’t fully recovered from the pandemic.

But Bauer says it’s not all bad news.

“I would rather have people stay out of the labor force because they are able to retire with financial security than drive them back into the labor force because their situations have become more precarious,” she says.

Of course, these are uncertain economic times. Inflation is at 8%. The stock market tanked, sending Hebert’s investment accounts down about 20% this year.

Hebert is not overly worried yet. He purchased a fixer-upper in North Carolina back when interest rates were still 3% and recently put his house in Maryland on the market. Once that sells, he thinks he’ll be able to ride out the downturn in the markets. And if not, he has a plan B.

“I could work. I could get a part-time job,” he says.

But not now. He’s too busy planning his many retirement hobbies, including riding his motorcycle on the mountain roads of western North Carolina.

9(MDU1ODUxOTA3MDE2MDQwNjY2NjEyM2Q3ZA000))