News

Ohio has mandated schools follow the science of reading. Many southeast Ohio schools were one step ahead

By: Theo Peck-Suzuki | Report for America

Posted on:

JACKSONVILLE, Ohio (WOUB/Report for America) — Sommer McCorkle knew early on that her son was behind in reading.

“We had been working with a tutor, and I was working with him at home,” McCorkle recalled. As a curriculum director, she knew the importance of the upcoming third grade reading test. She wanted her son to do well.

But he didn’t.

“His score was so low, I didn’t think he would be able to pass. And here I’m a curriculum director, and I don’t know what to do,” McCorkle said. “That was, as a parent” — she paused — “so hard for me.”

McCorkle began digging into the science of reading: decades of research into how people learn to read, down to the neurological level. The term itself has become a point of contention after debunking an enormously popular teaching method called balanced literacy. Some have called the conflict “the reading wars.” But for McCorkle, what mattered most was helping her son.

“I couldn’t just go home from my class and sleep, this was my own child,” McCorkle said. “It really set me on fire.”

“Our curricula, our national curricula, were really failing all students by not including … all of the evidence base the National Reading Panel had recommended,” McCorkle said. “This was a pervasive, national system problem that I knew I had to be a part of correcting.”

That was ten years ago. Today, McCorkle is entering her second year as the curriculum director of Athens City Schools, where she is helping oversee the district’s transition to a science of reading curriculum. Athens was previously using a balanced literacy curriculum it purchased in 2018.

“Many teachers here were recognizing that they were receiving students in the upper grades that did not have the explicit skills that they needed for decoding and writing,” McCorkle said.

What kids learn with the science of reading

The switch from balanced literacy to the science of reading can be a big lift for teachers. To understand why, it helps to know a bit about how both work.

Balanced literacy — along with a related method, whole language — puts most of the focus on creating a literature-rich environment, according to Fort Frye curriculum director Nichol Honaker. Surround kids with fascinating books, the thinking goes, and they’ll be motivated to read them. The problem, Honaker said, is that balanced literacy sidelines many of the concrete skills kids need to actually decode and understand words — for example, phonics, the practice of teaching how letters correlate to spoken sounds.

“When you talk to people who are proponents of balanced literacy, the first thing you’ll always hear them say is, ‘Well, it’s about teaching a child to love reading,’” Honaker said. “The science of reading would combat that by saying, ‘Well, no one’s going to love to read if they can’t read.’”

As whole language and balanced literacy curricula ascended, many new teachers were never shown how to teach things like phonics. They taught their students to recognize words by sight, but not necessarily how to sound out new words or work out what those words meant on their own. This wasn’t a disaster for every student, but it caused serious problems for some.

“My dad and my mom both really struggled with learning to read because they weren’t taught phonics. But then my son, who is 8 years old this year — they use the phonics curriculum with him. … He was able to start reading very quickly because of that,” Honaker said.

(It should be noted that balanced literacy curricula can include phonics. However, “if you look at those balanced literacy programs, the phonics component is always very minimal, as minimal as can be,” Honaker said.)

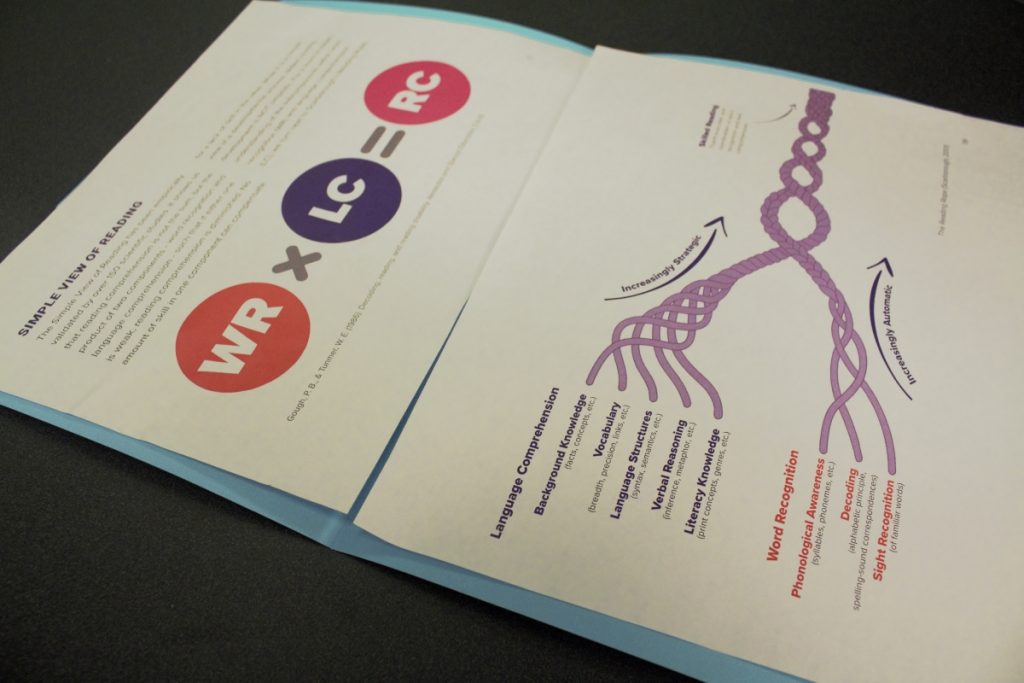

The science of reading is predicated on the notion that every child develops the same fundamental skills to read. These are sometimes presented as the “five pillars” — phonemic awareness, phonics, fluency, vocabulary and comprehension — or as a “Reading Rope,” which breaks reading into eight distinct but interwoven abilities.

Trimble literacy coach Heather Johnston said she got virtually no literacy training as an up-and-coming teacher.

“I got phrases like, ‘English is a funny language, it doesn’t make any sense!’” she said. “I got a lot more whole language and literature training. And when I went out into the field, that’s what I did.”

Like Sommer McCorkle, Johnston is now a big science of reading proponent. “For me, learning the brain science was really a big, a key turning point,” she said.

Today, Johnston keeps diagrams of the human brain on her phone and can explain language processing at the neurological level. That’s not something she could do at the start of her career.

When she initially learned this information, Johnston said, she was dumbfounded. “If this is science, and we can see that this is what works, why have been doing this other thing for so long?” she said.

In the classroom: word work and background knowledge

Among the various knickknacks Johnston keeps in her classroom are ziploc bags full of bright blue sand. She demonstrates an activity by pouring the sand into a red tray, which she gently shakes so the surface of the sand is smooth.

“Eyes on me. Your sound is, ‘Aah.’ Repeat,” Johnston says. “And then you would say, ‘“A” says “Aah.”’ And you would write an A.”

Moving one’s finger through the sand makes the exercise a multisensory experience. It’s a component of Orton-Gillingham, a premier approach to reading instruction for students with dyslexia that is fully in line with the science of reading.

“Feel that. With your finger,” Johnston says.

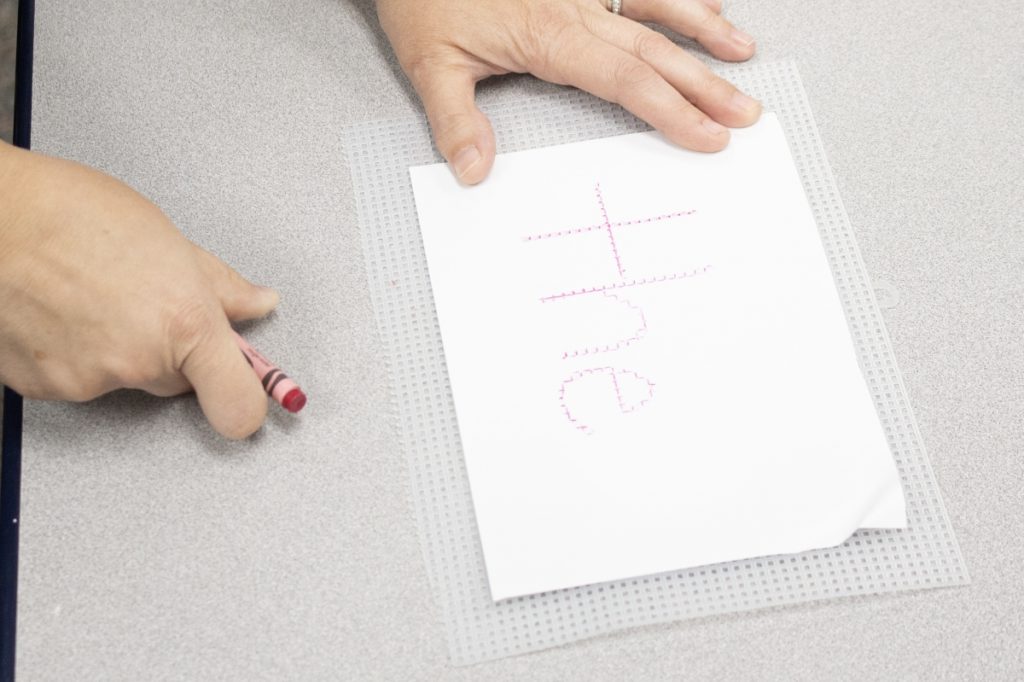

The crayon pressing against the mesh has given the letters a rough, waxy texture.

“It’s just a different modality, so it’s a different way to put it in your brain,” Johnston explained afterward. “We will have the kids air-write words, so that’s gross motor, that’s large motor because it’s coming from the shoulder. Whereas this (with the crayon and mesh) is small, fine motor.”

The point is to build skills — those eight strands that make up Scarborough’s Reading Rope — through drilling.

“In kindergarten and preschool classrooms, that’s where the majority of their time will be spent just learning how to produce those sounds,” said Nichol Honaker. “That’s that phonemic awareness component. And then once they have that foundation … then you’ll see them doing the word work. So whatever phonics pattern they’re working on that week, there’ll be some direct instruction on that.”

Even if some kids learn the skills much faster than others, they are fundamentally the same skills, Johnston said. That means everyone benefits from the science of reading, whether they have a condition like dyslexia or not.

In first grade, these students should be able to decode full sentences made up of these simple words and patterns. Honaker said this is not the case with balanced literacy.

“Often, you’ll see in the balanced literacy curriculum, in first grade, they might have connected text (sentences), but much of the words within those texts will not be decodable,” Honaker said. “You’ll see them just guessing at those words, and there’ll be a lot of pictures in this book so that when they do guess those words, they often guess the right word. But if you put that word by itself, they wouldn’t be able to decode it.”

If a kid is struggling with a skill, that reveals a need for intervention, which is to say, more practice, perhaps with an activity like a sand tray. This is what children like Sommer McCorkle’s son often need, but may not get in a balanced literacy environment. Such is the benefit, proponents say, of the science of reading: It’s easier to spot problems early and fix them.

Honaker said it typically takes 15 to 30 minutes of intervention a week to get a kindergartener back on track in reading. After that, the time required to catch students up increases dramatically.

“First grade, it goes to like, 60 to 90 minutes a week,” Honaker said. “By the time they get to third or fourth grade, you’re looking at, they need like 90 minutes a day of intervention.” That’s just not feasible during a regular school day.

By the time students get to third grade, they’re mostly done with this “word work” and have moved onto more complex concepts like morphology — things like prefixes and suffixes. As time goes on, they may focus more on “language comprehension”: a broader awareness of what words and ideas mean, which the science of reading has found to be distinct from word recognition but equally crucial to reading.

“Students might be able to decode a word, but can they really comprehend what they’re reading? Part of it is, students that have a rich background knowledge, rich vocabulary, they are able to not only decode, but often … to better understand,” Rouse said.

She cited an example she encountered while researching the science of reading: reading an article about cricket, a sport many Americans know only by name.

“I’m a fantastic reader. I can break down words like a champion. But I don’t know anything about cricket,” Rouse said. “So as I’m reading this article, I’m not comprehending anything, because I don’t have any background knowledge at all.”

To comply with the state mandate, Alexander is fully implementing a science of reading-aligned curriculum this year. It will include deep instruction in specific topics like the human digestive system or the War of 1812 — the idea being that enhancing their background knowledge will boost student reading comprehension.

Making the switch

At the time the state mandate came down, every school district interviewed for this article — Athens, Alexander, Logan-Hocking, Marietta, Fort Frye, and Trimble — had at least been looking into the science of reading. Some had already made the switch; others had to speed up when they realized the state was actually going to require specifically-approved curricula.

“I was quite surprised that Ohio issued these mandates, because we are kind of a ‘local control’ state, as they call it. And I don’t think I expected to see the level of commitment and dedication that they have declared,” said Fort Frye’s Honaker.

By the time the state made its decision, Honaker was already well on her way to converting Fort Frye to a science of reading district. She started as curriculum director five years ago, after which she began having conversations with the superintendent about changing the reading curriculum.

“Getting leadership on board first, that’s always your first stop,” Honaker said.

After that, Honaker went to the Fort Frye elementary principals. “If you don’t get your principals on board, you’re never going to get anywhere,” she said.

Honaker said both her principals were initially strong balanced literacy proponents. Still, Honaker persevered.

“I found one teacher that I built a relationship with very quickly, and I gave her a new curriculum … just a very simple phonemic awareness curriculum. It’s called Heggerty and it only takes a teacher 10 minutes a day to implement,” Honaker said.

She asked the teacher to give Heggerty a try and share her thoughts.

“And that was all I had to do. I gave that to her and it spread like wildfire. She started using it, then everyone in that school wanted it, then everyone in my other elementary school started hearing … how exciting it was,” Honaker recalled.

Fleming started his position four years ago with a bruising revamp of the district’s math curriculum. He said he didn’t want to repeat that experience for reading.

“So before the mandate, before any of those pieces, we had about 18 months where we invited the community, administrators, teachers, parents, business leaders, anybody in our community to come and learn about the science of reading,” he said.

Alexander curriculum director Megan Karr said the state mandate sped up changes that were already taking place in her district.

“Our regular instruction was still very much balanced literacy, but our intervention program, we had already shifted to some programming that was very much aligned (with the science of reading),” Karr said.

Although the new mandate created some challenges — the list of approved curricula took months to come out, creating uncertainty for districts that needed to make changes — Rouse, the elementary principal, said Alexander benefitted from robust support from its board and community.

“I think a large part of that is that we had our district’s support from the get-go. Not every school district across the state of Ohio has been able to provide their staff with the fantastic professional development opportunities that we have,” Rouse said.

Equity and justice for every reader

Trimble Elementary, where Heather Johnston now works, was a relatively early adopter of the science of reading. The district changed ten years ago, long before many of its peers in southeast Ohio.

Trimble curriculum director Diane Hobson said the move was driven by need.

“It’s because our students come to us not ready to learn,” Hobson explained. “They don’t have the number of words in their word bank, in their mind, when they come to us. Vocabulary isn’t as” — she paused.

“Robust?” suggested Heather Johnston.

“Yes, that’s a good word,” Hobson said.

Johnston went on, “We often have kids who come to kindergarten who’ve never stepped foot in an educational setting. So, they don’t know how to rhyme, they don’t know how to have a conversation with another kid.”

These are the kids the science of reading is really supposed to help. Hobson said it has: Trimble’s reading scores have improved in the last decade, with one notable dip at the start of the pandemic. But Trimble’s scores still aren’t great — its 2023 state report card gave it just two stars for early literacy, compared to three for Athens, Alexander and Fort Frye and four for Logan-Hocking. Marietta also received two stars.

Attendance and behavior, said Hobson.

“You know, with poverty comes so many other issues, and attendance, often, is one of them,” she said. “They don’t see the value in education, they just don’t come to school. Parents might be working late shifts at night, so they don’t get up in the morning.”

And no curriculum works if kids don’t come to school, or if they’re acting out in class. Trimble has been devastated by the opioid epidemic, and the elementary school has multiple mental health professionals and a caseworker from Athens County Children Services on hand to support students. Trimble has also introduced free preschool — a way to catch those early language issues even sooner — and already has a waiting list.

For Sommer McCorkle, the Athens curriculum director whose son has dyslexia, the impact of socioeconomic factors on school only makes the science of reading more important.

“I do think the science of reading, and implementing the science of reading … is one of the most important social justice topics of our time,” McCorkle said. “Literacy is the key to freedom. … Those who hold the pen hold the power. And I want every one of our students that leaves Athens, or any district where I’m working — every district in our country — to leave our doors critically literate, and able to … accomplish anything they want. To make their community, and make their country, and make their world a better place.”