News

A Family’s Struggle Against Time

< < Back to a-familys-struggle-against-time

A tall, bearded 18-year-old brushes his teeth as his sits on a wide seat covered with absorbent pads in his bedroom. The television in front of him plays a musical episode of a 90’s Disney Channel show. Latna Bennington, a new addition to the set of hired nurses that help Bubba when family members aren’t available, offers him a cup to spit out the toothpaste. His teeth cleaned, Bennington gathers a bowl of water, a razor, and nail clippers to spruce Bubba up. Thanksgiving is coming up, and Bubba’s mother wants to make sure he’s cleaned up for when his stepfather comes home from the correctional facility for the holiday.

Donald Francis, affectionately called Bubba by his family, has been fighting a rare genetic disorder that is steadily destroying his body and mind.

Bubba lives in a small home in the rural countryside of Meigs County, Ohio. He is the youngest child of a family that includes two sisters and two half-sisters.

“He’s a really good kid, he’s always been really good. He was a good baby, never any trouble. He went through all the hell his four sisters gave him, dressing him up in dresses and make up,” explains Michele Barley, Bubba’s biological mother.

Until the age of 8, Bubba had what many would consider a typical childhood, but that is when his parents starting to notice something was amiss.

“He had a BB gun and he was really good on the target. He’d hit the target 99 out of 100 times. He’d do it right-handed, left-handed, it didn’t matter, he’d switch it up…that’s where we noticed it. Strange, but that’s where we noticed it.”

Bubba’s inaccuracies with his BB gun is when his muscle failure became apparent to his family. As Bubba grew older, other symptoms began presenting themselves; he couldn’t run like other children his age and he couldn’t catch or throw a football. So Michele and her husband decided to bring Bubba to Children’s Hospital in Columbus, Ohio, launching a cycle of visits and tests at the hospital every three months as doctors tried to figure out what was wrong. Roughly six years later the family finally had a diagnosis.

“The doctor was really blunt out in front of Bub, told him he had a mutation and a mitochondrial disorder and that it was a terminal disease. But he didn’t use such nice words. He said it was deadly, that he would die early. So driving home from Columbus, Bubba says, ‘Am I a mutant?’…this is before, when he could really speak and when he could understand…and I told him, ‘no,’ and he said, ‘I don’t want to die.’ I stopped the car. We sat there for a good half hour, 45 minutes until we were calm again and drove on home.”

But Bubba’s initial diagnosis was incorrect and he was eventually diagnosed with a more aggressive condition: Niemann-Pick Type-C, or NPC.

NPC is a progressive neurological disorder that degrades a patient’s brain functions and muscular movement, including muscular movement required for some organs to function properly. The disorder causes things like: cerebral palsy, slurred speech, difficulty swallowing, epilepsy, altered sleep cycles, limited muscle movement (including moving eyes), psychosis, dementia, seizures, and bipolar disorder. The genetic disorder affects approximately every 1:150,000 people. Patients around Bubba’s age usually only live into their early twenties.

As NPC slowly degrades Bubba’s mind and body his family does what they can to fight back. Michele tries to keep Bubba’s brain working by making him play some sort of memory or board game at least an hour every day. He currently has the comprehension of a 3 or 4-year-old. Dementia caused by NPC along with the loss of muscle control means Bubba is trapped in his body and mind. “If you ask him how old he is, he has different ages. For the longest time he was 14,” said Michele.

Amidst Bubba’s struggles, music has become a source of happiness for him. Around the age of 12, he fell in love with Bobbaflex, a hard-rock band from Point Pleasant, West Virginia, that his parents occasionally listened to.

“I’ve never seen someone so infatuated with a band, and I’ve had four teenage daughters,” said Michele, laughing. “He got something out of it. You could just feel it, he was really getting into the groove of this music and it just touched him somewhere. It was something that we didn’t see very often. We’d never see him enjoy something, he was usually in pain, but when he heard Bobbaflex he was happy, and danced and sang, just like a normal teenage boy, a healthy teenage boy.”

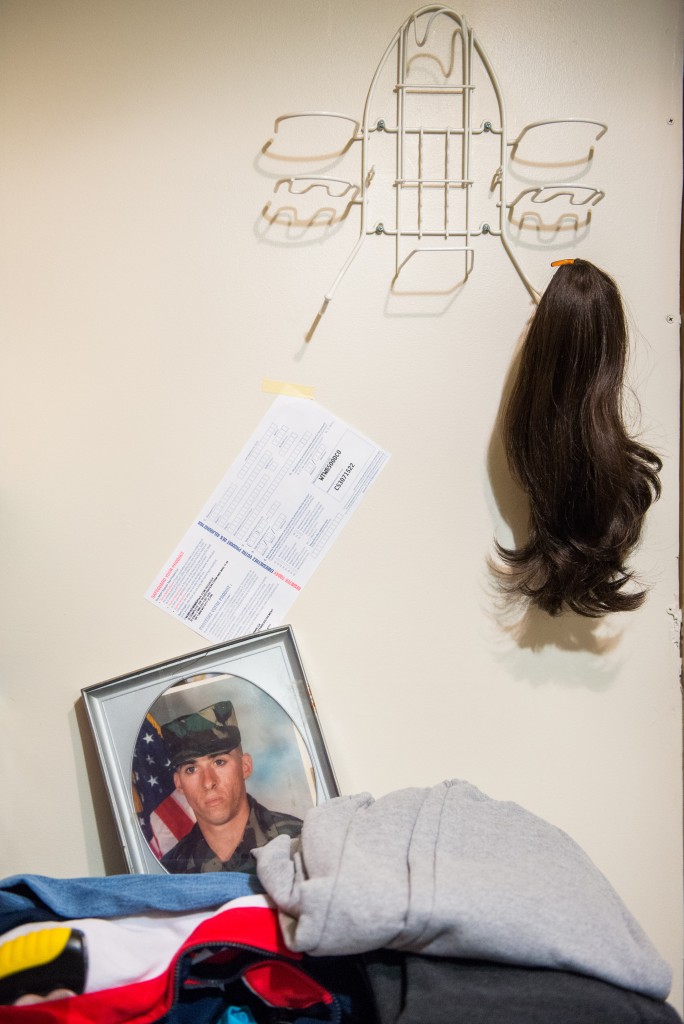

Now unable to move much, Bubba spends many hours of the day sitting and watching television, often Bobbaflex music videos his mother burned onto a disk for him. He sings along to his favorite songs with the remaining speech he has left. The combination of muscular and neurological degradation is hindering his speech, and eventually he won’t be able to speak at all. Bubba still musters a few dance moves from time to time while he stands precariously in his room outfitted with posters of bands, superheroes, and a Sports Illustrated swimsuit model, shelves filled with DVDs, toys, stuffed animals, diapers, and medical machines.

But since August, Bubba’s had to spend his time singing and watching Bobbaflex videos without his primary caregiver; his stepfather, Dwayne “Duey” Barley.

“Duey” was incarcerated at the Southeastern Probation Treatment Alternative (SEPTA) Correctional Facility in Nelsonville, Ohio, for crossing state lines and breaking his probation.

“It’s an adjustment, how Duey’s been gone for three months,” said Michele. Usually she would work during the day and Duey would watch after Bubba. Now with Duey incarcerated until February, Michele had to find nurses to take care of Bubba while she went to work. Bubba’s stepsister Leah Barley also had to step in and help, diligently taking care of her stepbrother when she could. In November, nurse Latna Bennington became Bubba’s primary caretaker.

“He’s just one of a kind,” said Latna. “You can’t help but fall in love with him. Three days in I gave him a hug and he’s not forgotten it. Now he hugs me every time I go to leave. I got him to actually put his arm around me the other day and we danced.”

It’s Thanksgiving morning, and Dwayne “Duey” Barley is sipping his third cup of coffee before 9 a.m. within the walls of the SEPTA Correctional Facility. He waits for the announcement to crackle across the public address system for inmates with furloughs to sign out. He’s been granted an 8-hour furlough to go home and see his family for the holiday. He’s anxious. He often doesn’t get to see his wife and stepson, and especially other family. Though Bubba has no biological ties to Duey, he thinks of him as his own son and not a stepson.

Caring for Bubba has created a close relationship between Duey and his stepson. A relationship that doesn’t have much time left, making every day precious.“I’ve taken five months of my child’s life…I’ve robbed myself of that.”

The call goes out for furloughs and Duey joins several other inmates as they file out the doors lead by a security guard. A handful of running cars with driver’s doors open greet the men as they walk towards their family members and embrace, eager to spend the holiday together. Duey meets Michele with a hug and a kiss as Bubba and Leah sit in the backseat. As Duey takes his place in the passenger seat, the family’s white Maltese dog, Emily, excitedly greets him as they drive home.

Being back home, if only for the holiday, takes some readjustment. “It felt like our first date,” explained Michele. Duey greets his daughters as they trickle in, some with husbands and children of their own. He also spends some time with his brother, Tony Barley, lifting weights in his garage gym – something he hasn’t been able to do at SEPTA. The former bodybuilder isn’t as strong has he used to be.

While Thanksgiving dinner is prepared, Tiffany Francis, Bubba’s biological sister, remembers Thanksgiving two years ago.

“Our first Thanksgiving after he got the feeding tube we all sat down to eat and he started crying. That was a big deal as he is a really happy kid,” said Tiffany. Michele remembers, “He said, ‘Why do you all have to eat in front of me?’ and Thanksgiving was over. None of us could eat.”

“After that I lost my appetite,” said Tiffany. “That’s when it really hit me that nothing would be the same again.”

Dinner is ready and all 11 of Bubba’s family and extended family sit down for Thanksgiving. About a year ago, when Bubba could speak more frequently, he stopped asking for things to eat. But, on special occasions, his family allows him to be fed carefully prepared foods orally. If the food is the right consistency and temperature, he can get in down without choking. Eventually this will be impossible, but this Thanksgiving he tasted warm mashed potatoes and pumpkin pie.

Family time can be a precious thing. As children grow up and move away to start their own families, the demands of life can mean less time together, save those special occasions like birthdays and holidays. The Barley family is no exception, but Bubba’s condition makes every moment of family time all that more precious.

“Just to know, that if this was his last Thanksgiving, that at least he could share it with the people he loves and people who love him. It’s worth more to me than anything,” said Tiffany.

The conversation moves to Bubba. He has steadily lost the ability to talk but when someone at the table tells a joke, Bubba utters a rare quick reply. A smile crosses his face as he laughs softly with his eyes closed. The entire table joins in with him.

It’s a bittersweet moment for Michele that brings back memories of another life.

“He told a joke, he was probably nine years old, and it was about a duck going into a hardware store looking for grapes,” she remembers. “It was so comical the way he would tell it. We always told him he should be a stand-up comedian. He told that same joke, I couldn’t tell you how many times. But like today, he wouldn’t be able to tell you that, he wouldn’t be able to tell a joke. He wouldn’t be able to speak it. It’s little memories like that that we have, that we get to hold onto.”

And the smile from Bubba at the Thanksgiving table is one of those moments worth savoring.

“I like to think he’s still in there, because he loves to laugh,”Michele said. “It’s times like that I wish I had a constant video camera.”