News

Labor Movement: Will ‘Right-To-Work’ States Attract More Businesses?

By: Becca Schimmel | Ohio Valley ReSource

Posted on:

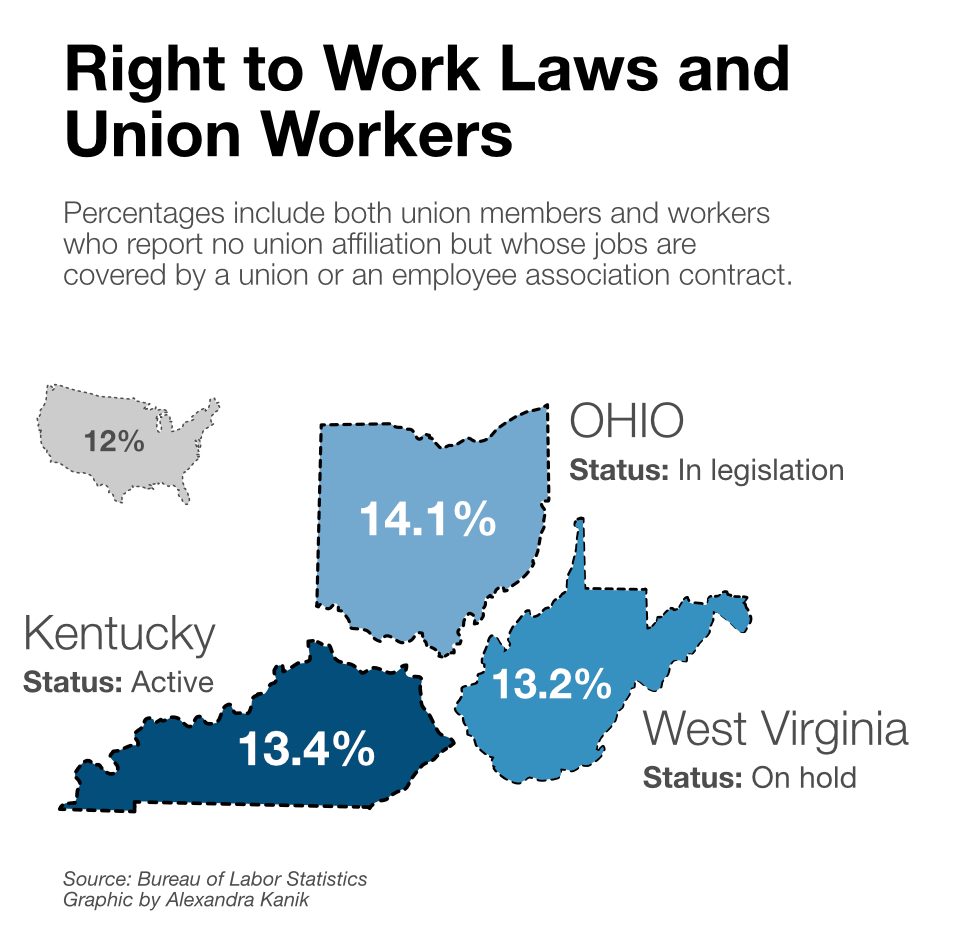

The Ohio Valley region once helped give rise to the labor movement. Now it’s shifting toward what’s known as right-to-work law. West Virginia and Kentucky have passed right-to-work laws and Ohio is considering a similar bill.

One of the big selling points for right-to-work proponents is that the law can attract new businesses. But opponents argue that there is little evidence to support the claim and that the potential benefits come at too high a cost to workers.

Big Choices

Mike Mullis is a site selection consultant who has spent 25 years helping global corporations, such as Toyota, pick the places where they will build major projects. He said some companies – particularly in manufacturing – will perk up when they hear the words “right to work.” However, that doesn’t mean businesses will come flocking to a state.

“The thing that is misunderstood by many people is that right to work does not guarantee you projects,” Mullis said,“it simply guarantees you more opportunity.”

He said other factors are more important, such as the skill of the workforce, infrastructure, and transportation. Mullis supports right to work, but he notes many oversimplify its connection to workplace growth.

A Business Perspective

Simply put, right-to-work laws prohibit a company or union from requiring workers to become union members as a condition of employment. The laws states pass also often go a step further. They eliminate the requirement for non-union workers to pay what are called “fair share fees.” Unions strongly object to that — as we’ll hear in a moment.

But Kenneth Troske, an economics professor at the University of Kentucky, said he thinks right-to-work laws should help states attract businesses.

“[It] sends a signal to businesses that, as a state, we are trying to make ourselves more open and friendly and flexible as possible for businesses that want to locate here,” Troske said.

He said businesses like the promise of flexible workplace schedules which can increase productivity.

“That’s essentially what the research shows, is that when plants become unionized, you see a decline in their productivity,” Troske said.

Explore our Right to Work timeline >>

Troske acknowledges that right-to-work laws are a “mixed bag” because, as unions argue, the flexibility that employers want can lead to exploitation of workers, which is why they need the protection of unions. But Troske argues that new businesses that locate in right-to-work states are competing with other businesses for the same pool of skilled workers. That means that even if wages drop it will not be as dramatic as opponents of the law suggest.

Businesses considering relocating do want to know about right-to-work status, he said, even if the region’s skilled workforce remains a top concern. Troske pointed out that the effect of right-to-work laws in the Ohio Valley region are not clear because the changes are too recent.

The Workers’ View

Ross Eisenbrey is vice president of the Economic Policy Institute, a nonprofit think tank focused on the needs of middle and low income workers. He said right-to-work laws have never been shown to make a difference in employment growth and he is skeptical of claims that the laws do much to attract new business.

“Corporate CEOs who answer surveys about the factors that determine where they locate, don’t even have right-to-work in the top ten factors that influence their decisions,” Eisenbrey said.

He doubts that businesses the issue to a priority in deciding locations for investment because only 6 percent of private sector workers are unionized. And he warns that anyone hoping that the law will bring a dramatic increase in manufacturing jobs and new businesses will be disappointed.

“I don’t believe for a minute that that’s an important factor in a business decision about where it locates,” Eisenbrey said.

Eisenbrey pointed to economic evidence showing that right-to-work laws come at a cost in the form of weaker unions and lower wages. He said unions lead to higher wages, and generally have an impact of increasing wages by 10 to 15 percent compared to non-represented employees.

“As right-to-work reduces union finances and weakens the union’s ability to represent workers over time, wages go down,” Eisenbrey said. “And that’s what will happen eventually in West Virginia and Kentucky.”

Eisenbrey noted that while business-friendly legislators vote for right to work laws, many voters don’t. Historically when right to work laws are put to a statewide vote, they typically don’t pass.

Ohio’s experience with right-to-work proposals offer an example, he said. Such laws were first introduced in Ohio’s legislature in 1958 and didn’t pass. The legislature passed a law eliminating collective bargaining in 2011 only to have it overturned by a statewide vote later that year. Now the legislature is considering a right-to-work provision once again.

A Court Challenge

In West Virginia, a group of unions is suing the state over its right-to-work law, which passed last year. A judge placed a stay on the new law shortly after it was signed. Ken Hall is general secretary-treasurer with the Teamsters, one of the unions involved in the lawsuit.

Alexandra Kanik | Ohio Valley ReSource

Alexandra Kanik | Ohio Valley ReSource“If this was good for workers, why is it that eight of the ten states with the lowest per capita income are right-to-work states?” Hall said. “Why are the majority of the top 15 states with the highest rate of poverty right-to-work states?”

The union challenge to West Virginia’s law largely has to do with the effects on non-union employees in a unionized workplace. A little history helps to explain this.

The U.S. Supreme Court decided in a case in the 1970s that employees can’t be forced to join a union, but non-union employees could still be made to pay fair share fees for the benefits of a union workplace, such as collective bargaining.

Right-to-work laws often go a step further by eliminating the requirement for non-union members to pay what are called fair share fees, which are lower than full union dues. But the unions are still responsible for collective bargaining for those employees, and must defend them in the event of a grievance.

Hall feels it’s unfair that non-union workers get something for nothing. He said it means that right-to-work laws will weaken unions and hurt workers far more than they help an area generate new business.

The unions expect a decision on their challenge to West Virginia’s law in a couple of weeks. Kentucky is just beginning to implement its law and Ohio is just reviving debate on the issue. The real effect of right-to-work laws in this region once dominated by union labor remains to be seen.