News

The Struggle To Stay: Personal Stories Behind Population Loss

By: Glynis Board | Ohio Valley ReSource

Posted on:

Editor’s Note: Parts of Appalachia are bleeding population; the 2015 U.S. Census showed West Virginia was losing population faster than any other state. There’s a palpable struggle to leave, but also to stay in these hills.

West Virginia Public Broadcasting’s podcast, Inside Appalachia, has a new series of stories called “The Struggle to Stay”. Reporters have spent 6-12 months following the lives of 6 individuals as they decide if they will stay or leave home – and how they survive either way.

As people watch friends and neighbors move away, some want to join them, but can’t afford it. Others feel obligated to stay. Some are compelled to remain in Appalachia with dreams of turning their region into one that’s economically and culturally vibrant, while proving its value to the rest of the country.

“I’d love to be able to stay here,” said 32-year-old West Virginian Mark Combs. “The people are great. But it’s just dying. If you want to succeed you’ve gotta leave.”

Mark is an actor and an Iraqi war veteran. He thinks there has to be a better life, or at least better economic opportunities, elsewhere. He decided to head west for Los Angeles.

“I think the job market is so much larger out there than what it is here that jobs are going to be really easy to come by,” he said before he set out.

The reality turned out to be a little different than he expected.

The Numbers

Mark is among thousands of young people streaming out of the Ohio Valley’s small towns and rural counties. Census numbers show West Virginia is especially affected by this population drain.

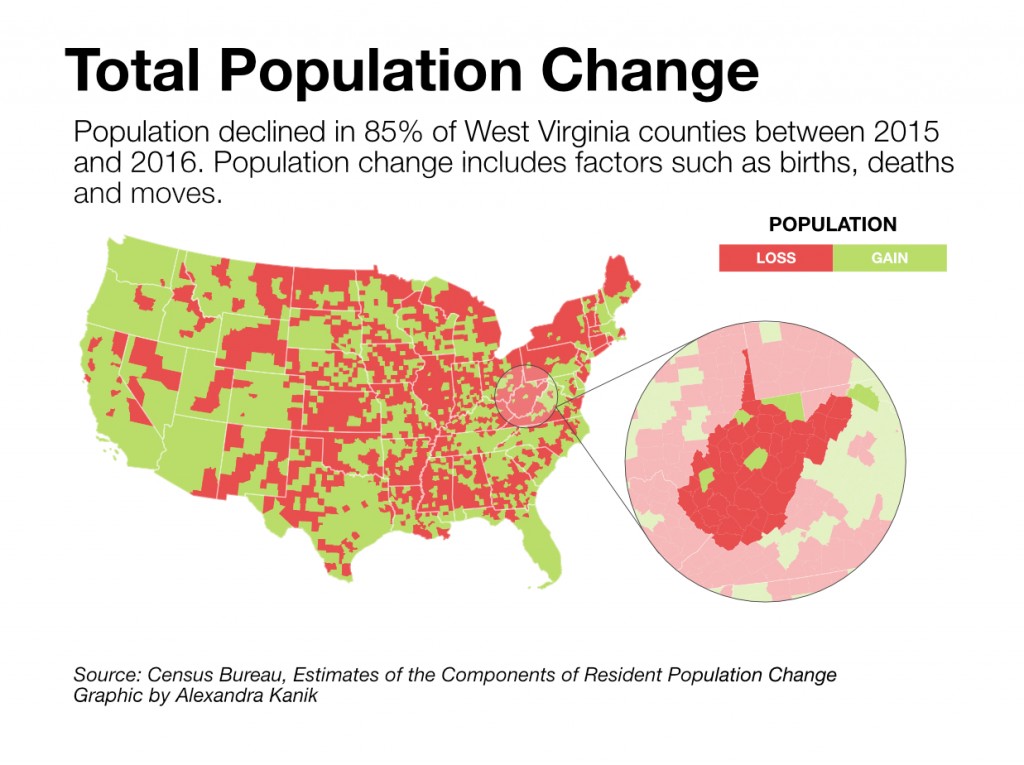

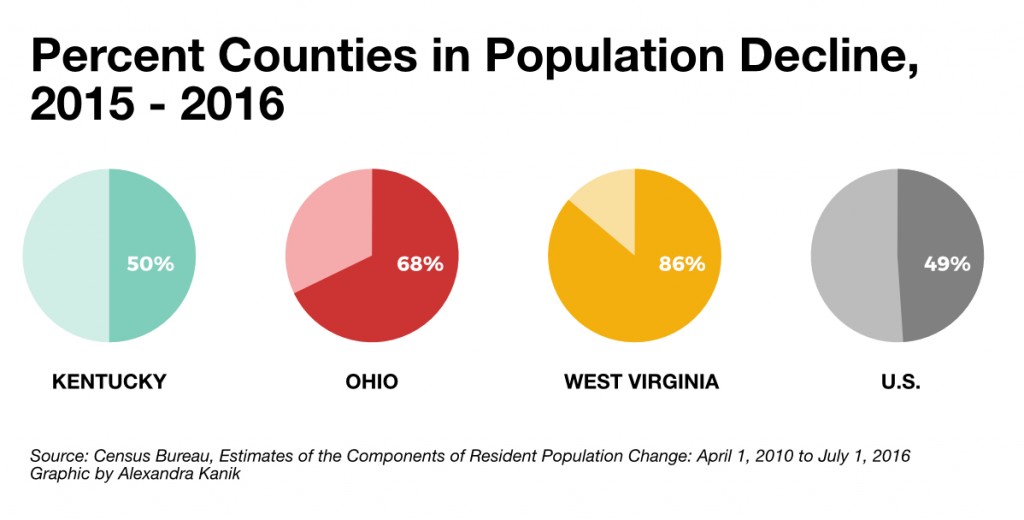

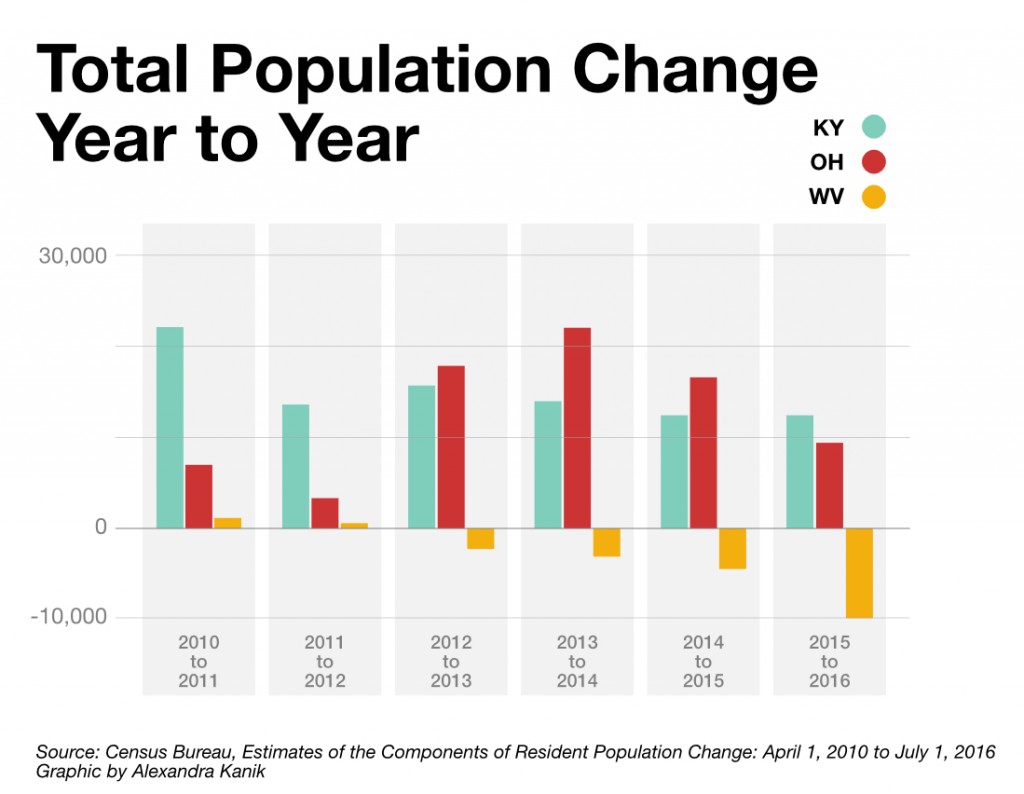

2015 Census Bureau estimates indicate that West Virginia was losing population faster than almost every other state due to a combination of the declining coal industry, emigration of young people, an aging population, and declining birth rate. While it’s not the only state losing population, West Virginia’s population loss is more pervasive throughout the state with 85 percent of counties experiencing a population loss between July 2015 and July 2016.

Thousands of other residents wrestle with the decision to stay or go. It’s a palpable part of what defines life in these hills and small towns.

In the “Struggle to Stay” series, producers at West Virginia Public Broadcasting and its partner organizations follow six people from the Ohio Valley region to get a better sense of the very personal ways these decisions play out. We track them for months to glean insights about what keeps people here, what pushes them away, and what their decisions mean for them and the region.

Our Struggling Subjects

Derek Akal, 21, is from Lynch, a former coal camp town in Harlan County, Kentucky. For generations, Derek’s family and others in this African-American community have found themselves leaving home to chase better wages. Derek left home with a college football scholarship. But a spinal injury took him off the field, so he came back.

Crystal Snyder is a 37-year-old single mother of two from southern West Virginia who wants to stay in the region, but worries about exposing her children to the region’s industrial pollution.

“When I think of the toxic Chemical Valley and Dupont and mountaintop removal and the dust,” Snyder said, “and when a map shows you people die earlier here than they do over here in Virginia, and your mother died at 41… it kind of makes you think, ‘Is it a good idea for me to leave my children here?’”

Colt Brogan, 20, is a native of Lincoln County who is learning to farm at his former high school through the Coalfield Development Corporation. Colt says he wants to stay in West Virginia but knows it can be tough to make a living here. He says his childhood was unstable, and he dreams of owning a farm and raising a family in West Virginia.

Kyra Soliel-Dawe, 20, lives in West Virginia’s eastern panhandle and aspires to work as an actor and form a small theater company in Shepherdstown. Kyra also identifies as genderqueer. Coming out to friends and family was tough. Would things be easier for Kyra in another community outside of Appalachia?

“This place is so beautiful,” Kyra said, “how would you ever want to leave it? And I hope that I’m not the only one that sees that, I hope that I’m not the only one that sees that there’s something really incredible happening here, and my fear of both leaving or staying is the fact that [my art] won’t ever get acknowledged unless I go elsewhere. But if I go elsewhere, it won’t be derived from this place — this beautiful, beautiful place.”

Dave Hathaway is a 38-year-old, laid-off coal miner who lives in Greene County, Pennsylvania. He and his family have lots of roots in Pennsylvania, and so he feels that he can’t leave. He and his wife just had a baby. She has a job and is the main breadwinner in his family.

Time to Listen

Long term reporting projects naturally require huge time investments. Asking our subjects to self-record and self-report is also a hallmark of this reporting project. In the process, hours of recorded audio, photos, video, voice mail recordings, text messages and a myriad of other digital fingerprints are collected to be studied for insight into daily routines, priorities, and life struggles. In this way we collaborate with subjects to examine and identify vulnerabilities that reveal truths about the shared struggles to leave or stay in the region.

Following Mark Combs over the course of a year, we found that the grass isn’t always greener elsewhere, even in sunny, southern California.

“So I am homeless, jobless, with $10 accessible to my name, on the complete opposite side of the country,” he reported from a mall parking lot in L.A. He struggles with financial burdens, loneliness, and difficult memories from his time in Iraq.

In “Struggle to Stay” we explore everything from the cost of living to to the emotional push and pull many in this region feel about moving away…and returning….and having to leave again. Do you have to leave to succeed? And is staying worth the hustle….the heartache…the risks of addiction, pollution and poverty?

That’s what we’re trying to find out.