News

Before Black Lung, The Hawks Nest Tunnel Disaster Killed Hundreds

By: Adelina Lancianese | NPR

Posted on:

Southern West Virginia is a playground for hikers, cyclists and rock climbers, but in the heart of that lush landscape rests the site of what many consider the worst industrial disaster in American history.

Today, from a picturesque overlook on the mountain above, tourists can see the gate of the Hawks Nest Tunnel, located on the New River in Gauley Bridge. There, water rushes through 16,240 feet of steel and rock.

But almost 90 years ago, thick clouds of dust blurred the eyes and choked the lungs of workers inside the tunnel. The project attracted thousands of men, hoping to find work during the Great Depression. Three-fourths were African-Americans fleeing the South.

“To these men, going to West Virginia was like going to heaven — a new land, a new promised land — and when they got here, they found that they had ended up in a hellhole,” says Matthew Watts, a minister and amateur historian in Charleston, W.Va.

Hundreds of workers would die after working in the tunnel from exposure to toxic silica dust, a mineral that slices the lung like shards of glass.

As NPR has reported, that same deadly dust has caused a resurgence of severe black lung disease among coal miners in Appalachia. Miners today are sickened younger and entering advanced stages of the disease more quickly. What’s more, federal regulators could have prevented it.

But before the modern epidemic plaguing coal miners, there was the Hawks Nest Tunnel disaster, a long-forgotten example of the occupational dangers of silica dust — and the government’s response to death on its doorstep.

“The town of the living dead”

The Union Carbide and Carbon Corp. began constructing the 3-mile tunnel in the spring of 1930. The company wanted to divert water from the New River to a plant downstream to generate power for iron smelting.

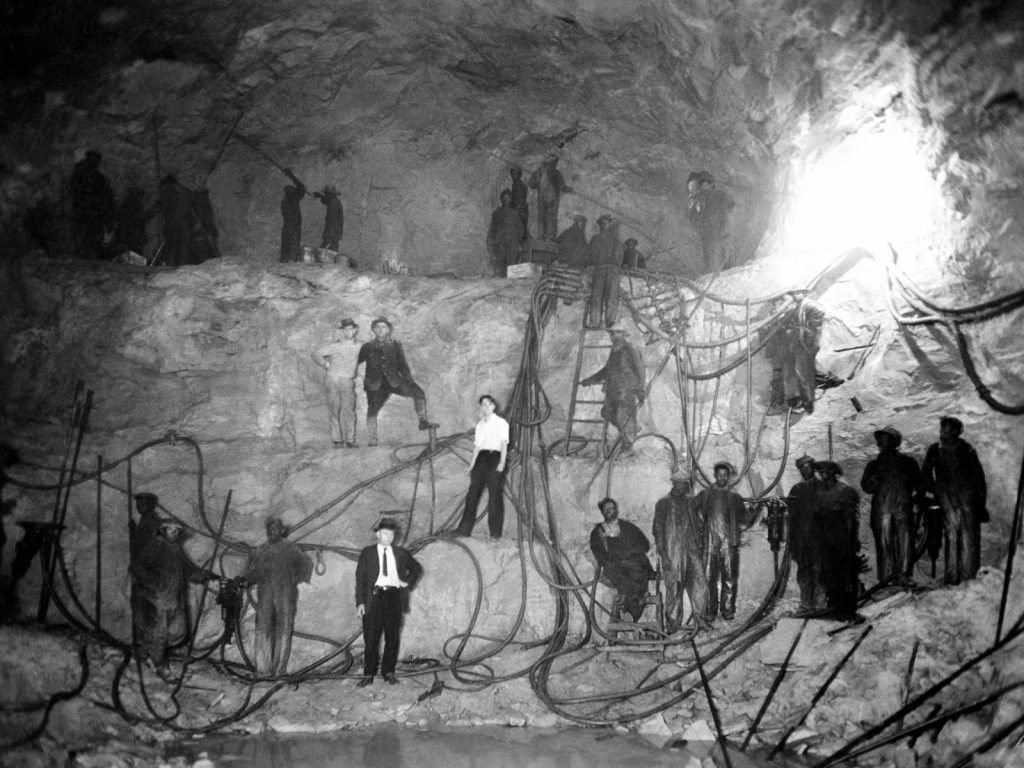

Nearly 3,000 workers labored in shifts of 10 or 15 hours. The tunnel, projected to be completed in four years, wrapped in 18 months. Workers drilled holes and then stacked dynamite to blast through sandstone.

“There was a nickname at the time for Gauley Bridge: the town of the living dead,” says local writer Catherine Venable Moore, “because there were so many sick workers, and also because they had this kind of ghostly presence when they were coming out of the tunnel being covered in this white silica dust.”

One of those workers was Dewey Flack, a 17- or 18-year-old African-American man. Flack’s age is unclear because — like many other black tunnel workers — only a few traces of his life and death remain.

Most likely, Watts says, Flack left his home in North Carolina with a one-way train ticket to West Virginia and the promise to send money to his parents and five younger siblings. He would never see them again.

“Young, healthy people breaking down”

Soon after construction began, men were already getting sick and dying at the tunnel.

“Each and every day I worked in that tunnel, I helped carry off 10 to 14 men who was overcome by the dust,” a Hawks Nest worker recalled in a 1936 newsreel. Photos taken during construction show ghostly images of workers shrouded in clouds of white dust.

According to Union Carbide documents, 80 percent of the workers became ill, died or walked off the job after six months.

The count of how many workers died varies. According to congressional testimony at the time, as many as 300 people died from silicosis, caused by exposure to silica dust. Cherniack estimates the number to be at least 764 workers — including Flack.

“They would become sick, profoundly short of breath, have severe weight loss, basically be unable to move and function and exercise themselves,” Cherniack says.

Flack died on May 20, 1931, two weeks after his last shift in the tunnel. His death certificate says he died of pneumonia, but according to Cherniack, company doctors often misdiagnosed worker deaths or attributed them to a disease they called “tunnelitis.”

The company would later use those death certificates to prove there were few, if any, silicosis deaths at the tunnel.

“They never knew the real truth”

Hundreds of local white men worked in the tunnel alongside black migrant workers like Flack, but conditions were even worse for the more than 2,000 black men, who made up the vast majority of the workforce.

Black workers who testified before Congress in 1936 said they were denied 30-minute breaks in clean air. They said if they got sick, supervisors would force them from bed at gunpoint.

According to death certificates, black workers were often buried in unmarked graves. In some cases, there was no attempt to notify the victim’s family, according to Watts.

But NPR did find one relative: Sheila Flack-Jones of Charlotte, N.C., who is Dewey Flack’s niece.

“My father mentioned when I was younger that he did have a brother but the brother he thought had run away,” Flack-Jones says of learning her uncle’s fate. “I’m heartbroken that my family died thinking that he had run away and they never knew the real truth.”

Five years after Flack and over 700 others began to contract silicosis, the U.S. House of Representatives Committee on Labor held a hearing on the Hawks Nest Tunnel disaster. Representatives from the tunnel companies declined to attend. One submitted a letter that called witness testimony “slanderous rumors and hearsay.”

“We know of no case of silicosis contracted on this job,” the letter concluded.

The congressional committee said the tunnel was completed with “grave and inhuman disregard for all consideration for the health, lives, and future of the employees.”

Congress took no action against the companies, but that same year it passed a law requiring the use of respirators in dusty working conditions.

More than 500 lawsuits were filed against Union Carbide and a contractor, Rinehart & Dennis, many of which were settled out of court.

Dow Chemical, which purchased Union Carbide in 2001, did not respond to NPR’s requests for an interview.

“Historical amnesia”

Flack-Jones plans to hold her own memorial for her uncle Dewey.

“I’m really, really angry. I am heartbroken,” Flack-Jones says. “Do I mourn for my uncle, the one that I never knew? Do I mourn for my family because they thought he had left? Or do I mourn for what he would have become had he lived?”

Watts worked at Union Carbide as an engineer for two decades. He also grew up just miles from the tunnel but had heard of it only a few years ago.

“Anything that is dark about what had happened to African-American people in particular in this state, it is as if it did not happen,” Watts says. “We don’t talk about it. And that’s the nature of West Virginia. We live with the historical amnesia, historical denial.”

Whippoorwill Cemetery in Summersville, W.Va., is Flack’s final resting place. Records suggest that when Flack died, an undertaker loaded his body onto a wagon with others to bury together.

According to Yeager, there was a contract with the undertaker: $50 for each body buried. When the undertaker ran out of room in an old slave cemetery, he buried 40 additional men in plain coffins in a mass grave on his family’s farm.

In the 1970s, the farm was excavated to make way for a new road, and the bodies of the workers were reburied at Whippoorwill. The cemetery was abandoned until Yeager found it and restored it, locating each grave with radar equipment. She is now the cemetery’s lone caretaker.

At a weekly visit, she assesses the damage from a recent thunderstorm: fallen branches and loose cobblestones. She pauses at a grave, caving in from decades in the soft dirt.

“This is pitiful because that’s sunken down,” Yeager says, shaking her head. “That’s where the casket is. Now that shouldn’t be that way at all.” She sucks in air through her teeth, holding back tears. “That is sad.”

This grave is one of around 40. They’re scattered throughout the property, all identical, and each marked by a single wooden cross. It’s impossible to know which one belongs to Flack.

NPR’s Howard Berkes and Barbara Van Woerkom contributed to this report.

9(MDI4ODU1ODA1MDE0ODA3MTMyMDY2MTJiNQ000))