News

Labor organizing in the Ohio Valley goes beyond coal

By: Katie Meyers | Ohio Valley ReSource

Posted on:

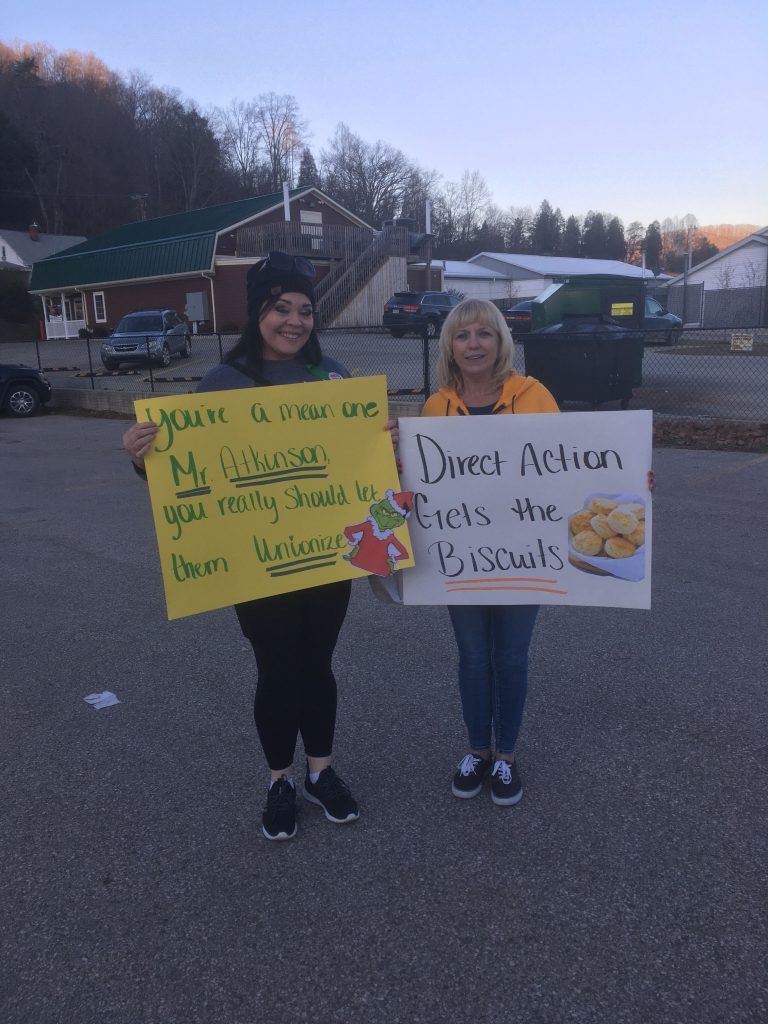

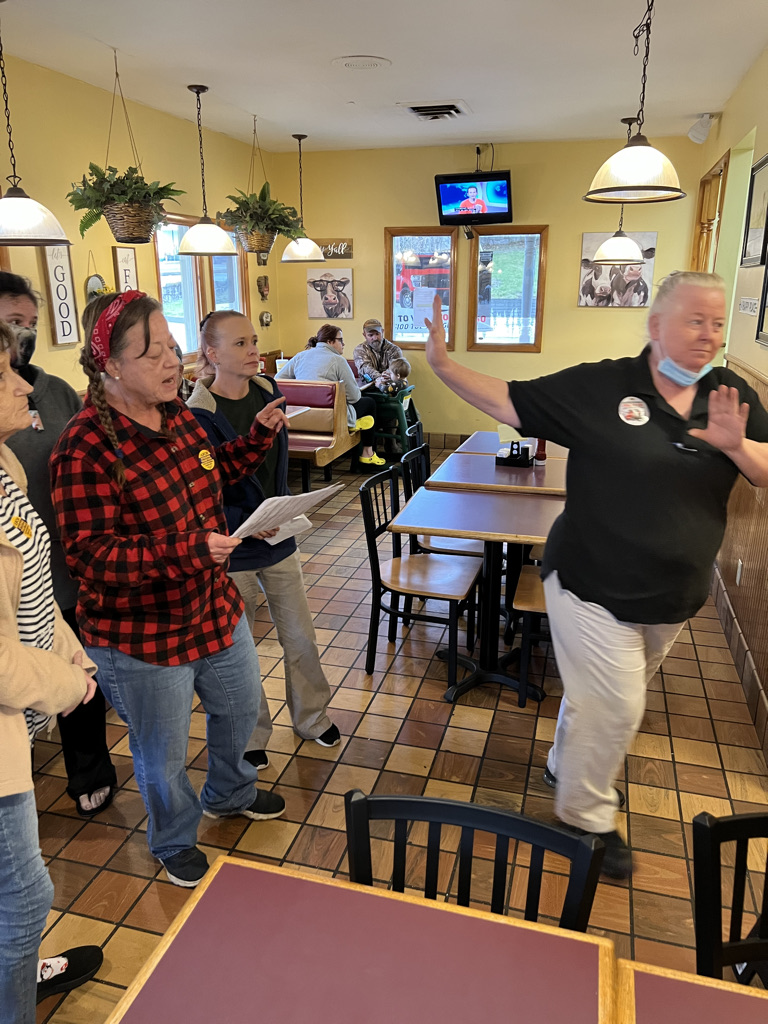

ELKVIEW, W.Va. (OVR) — In late December, West Virginia union members and supporters gathered in the small town of Elkview, about 20 minutes outside of Charleston. Dozens of linemen, coal miners, educators, plumbers and others lined up by the side of the road in front of Tudor’s Biscuit World to show their support for the local fast food shop’s unionization effort.

Tudor’s has a hold on the West Virginia imagination — it’s the state’s signature breakfast chain, where hungry travelers can pick from about twenty varieties of creatively-named, biscuit-based breakfast sandwiches. Workers at the Elkview location of the fast food chain have been in a months-long unionization effort, born after years of grievances about alleged verbal abuse, low pay and long hours.

During the rally, one of the organizers, Cynthia Nicholson, shouted along with the crowd chanting “Get up! Get down! Elkview is a union town!” Cynthia helped spearhead the union effort because, she said, she had less to lose. She makes ends meet with a union pension from her recently deceased husband, and had taken the job alongside her son, Daniel, as a way to introduce some structure into her life.

Discontent smoldered at the small-town Tudor’s for years, but the combination of the COVID-19 pandemic and a perception of increased union activity stoked the flames.

Current employee Jennifer Patton said the $9.50 an hour job, which does not include benefits, made her frequently feel unsafe.

“I worked with somebody for three days consecutively […] that tested positive for COVID on that Saturday, and they did not tell us at all,” Patton said.

When she went to the company’s HR department, she said she was told she didn’t need to know when co-workers tested positive for COVID-19.

Grievances across industries

Union leaders and reporters called the nation’s tumultuous autumn a “strikewave” — a season of simmering discontent in the American working class, featuring household names like Kelloggs and Nabisco. In West Virginia, the year culminated in a series of tumultuous events, from strikes to union drives, across Huntington, Charleston and the southern coalfields.

Though West Virginia has long been associated with coal miners’ strikes, the recent actions took place in industries that represent a broader swath of West Virginians across different walks of life — people who work in healthcare, fast food, steel and nonprofits.

Huntington, West Virginia has a long history as a union town. Workers at Cabell Huntington Hospital and the Warren Buffett-owned Special Metals plant cited that background as an inspiration for their autumn strikes, both of which resulted in contentious contract negotiations, as the ReSource reported in November.

Workers from both companies cited safety issues and employer-proposed reductions in health benefits as a primary reason for the walkouts.

Fran Barker operates the “pickle line” at Special Metals — a dangerous process that uses acid to treat metal.

“The thing that upsets me the most is right before the strike, we had a plant wide shut down for safety,” Barker said. “And things weren’t fixed […] so how do you expect us to work safely?”

Barker and some of her female coworkers, who call themselves the “Women of Steel,” made breakfast, lunch, dinner and holiday to-go meals for their striking colleagues. They were hopeful negotiations in December would result in a favorable outcome, but that didn’t happen.

Both Special Metals and Cabell Huntington Hospital hired temporary, highly-paid replacement workers during the strike. Cabell Huntington Hospital resolved negotiations in early December with a contract, and nurses have been back to work for almost two months. Privately, some expressed frustration that the contract didn’t go far enough, and included a reduction in benefits for retirees.

And in January, after picketing through Christmas, 75 workers at Special Metals were served with layoff notices, effective Feb. 7.

Employer retaliation is a reality

Public awareness of labor issues is growing but labor unions still face huge challenges.

Maxim Baru, an organizer with International Workers of the World, spent the past months helping organize staff of the Ohio Valley Environmental Coalition, a regional nonprofit, after complaints of long hours, sleepless nights and low pay.

“Just because there’s a new sense of vibrancy doesn’t make the situation totally more advantaged,” Baru said. “A lot of employers still have enormous financial and political advantages over their employees.”

OVEC’s board retaliated sharply, firing two employees, according to former organizer Brendan Muckian-Bates.

“I think that’s one of the things that frustrates me the most about this whole thing is we didn’t even get to present a path forward for OVEC,” Muckian-Bates said.

Employees filed four unfair labor practice suits to recoup their pay. In November, the company’s board dissolved the organization instead of recognizing the union. The National Labor Relations Board is now attempting to extract back pay from the company for the two fired employees. A judge has frozen the nonprofit’s assets.

Baru said organizing nonprofits and other industries has been challenging, and many workplaces require a different approach than the old-school shop floor once did.

“If we deliver that demand by continuing to do a kind of one-size-fits-all cookie cutter prefabricated unionization drive, we’re going to disappoint a lot of people,” Baru said. “The process of unionizing can sometimes be very lengthy.”

At Tudor’s, workers see high turnover as a major challenge for the organizing effort. Though 80% of the store initially signed union cards, many of the signers no longer work at the store, leaving them with a much slighter majority.

Cynthia Nicholson and Jennifer Patton, two of the organizing workers at Tudor’s Biscuit World, were suspended in January in what they say was a union-busting move.

Tudor’s Biscuit World did not voluntarily recognize their employees’ new union with the UFCW 400, so Nicholson and her coworkers filed for an election with the National Labor Relations Board. Employees sent in their ballots in December. The NLRB will announce the results on Jan. 25.

If the Elkview Tudor’s workers win the election, they will be one of the first unionized fast-food restaurants in the United States — after Burgerville in Portland, Oregon, which signed its contract in November.

Meanwhile a bill in Congress could have a rippling effect on workers’ lives throughout the Ohio Valley. The Protecting the Right to Organize Act, elements of which are in the Build Back Better Act, would protect workers from employer interference in union efforts, guarantee legal protection from employer retaliation and more. But the measure is still stalled in the U.S. Senate.

A movement that reflects the region

Popular perception of labor activity in Central Appalachia tends to associate picket lines with coal miners. But Dr. Jessie Wilkerson, a historian at West Virginia University, says that doesn’t recognize the full picture of the region’s labor history.

For instance, during the time of the 1973 Brookside strike in Harlan, Kentucky–made famous by films like Harlan County, USA, and monikers like “Bloody Harlan”–there was a hospital strike in Pike County, and the workers were mostly women.

“Those workers who were on strike were often going to each other’s picket lines,” Wilkerson said. “But it’s only one of those that gets memorialized and enshrined as part of Appalachian labor history.”

Healthcare workers also have a high share of representation in the Ohio Valley, particularly in rural areas, as a rare service that can’t be outsourced. The region’s healthcare workforce is mostly comprised of women, particularly in lower-ranking jobs.

Working conditions are different these days than in the mid-twentieth century, too — less shop floor, more job-hopping, gig work and short-term contracts. Wilkerson likened it to the 1930s era before the New Deal, a time when precarious work was more common than in the postwar boom, and workers had to organize across racial and ethnic lines, and across industries, in order to win.

“One thing the pandemic has done is put more attention on precarious workers’ experiences,” Wilkerson said.

And that labor history is an inspiration to the employees of the Elkview Tudor’s Biscuit World.

Daniel Nicholson, a former steamfitter and current Tudor’s worker, said organizing is educational—not just for his coworkers, but for others like them. Even if they don’t win their union, he said they’re paving the way for other people who might want to try.

“We reminded people that, you know, West Virginia is one of the birthplaces of organized labor in the 1920s,” Nicholson said.

Nicholson said he thinks about how in the old days, coal company owners threatened union mine workers with violence. When asked if he thinks companies would really threaten their workers’ lives in this day and age, he shrugged and laughed. Maybe not today, he said.

“But you give somebody an inch and they take a mile,” Nicholson said.

The company has not responded to a request for comment from the Ohio Valley ReSource. A Tudor’s representative told the West Virginia Gazette-Mail in November, that the company already protects their workers, and they don’t believe a union is needed.