Communiqué

Born into slavery yet he became one of the most influential voices for democracy, “Becoming Frederick Douglas” – January 16 at 9 pm

< < Back toBECOMING FREDERICK DOUGLASS

Tuesday, January 16 at 9:00 pm

Acclaimed Actor Wendell Pierce Is the Voice of Frederick Douglass in New Documentary Directed by Oscar®-Nominated Filmmaker Stanley Nelson and Nicole London

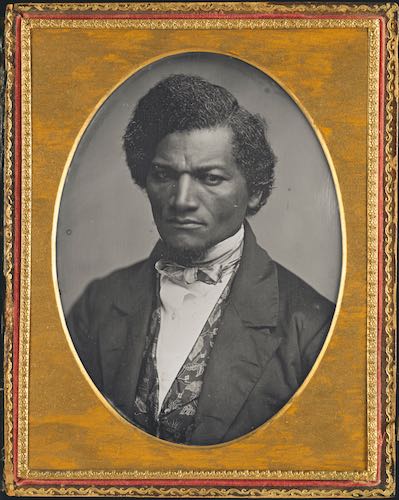

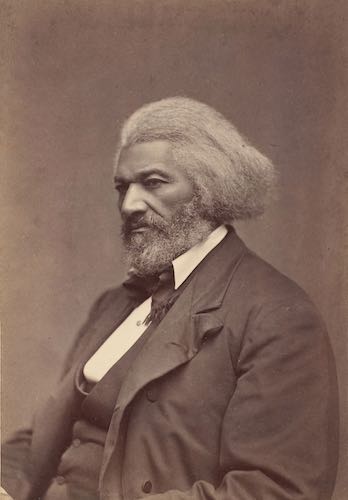

BECOMING FREDERICK DOUGLASS explores the inspiring story of how a man born into slavery transformed himself into one of the most prominent statesmen and influential voices for democracy in American history. Using his writings, images and words to follow his rise to prominence against all odds, the film is rooted in the singular truth of Douglass’s life: his insistence on controlling his own narrative and his lifelong determined pursuit of the right to freedom and complete equality for African Americans.

A co-production of Firelight Films and Maryland Public Television (MPT), the film is executive produced by Stanley Nelson and Lynne Robinson and produced and directed by Nelson and Nicole London.

“Given that Frederick Douglass was one of the most prolific and powerful orators of his time, we were interested in exploring how he created and controlled his image, and ultimately how he used it to shift public opinion around abolition,” Nelson said. “It was such a gift to have the inimitable Wendell Pierce provide the voice of Douglass to bring his words to life. Wendell’s dynamic performance, coupled with the many stunning photographs taken throughout Douglass’s lifetime, show how Douglass evolved to become one of the most influential and enduring social justice activists in American history.”

Born in 1818 in Maryland, Frederick Douglass escaped from slavery in 1838 and went on to become many things: abolitionist, autobiographer, essayist, diplomat, orator, editor, philosopher, political theorist, newspaper publisher and social reformer. And considering his trajectory — from enslaved to elder statesman — he was arguably the most accomplished man of his time.

For decades, Douglass was the most famous Black person in the world. More Americans heard him speak than any other contemporary, with the possible exception of Mark Twain. His lectures and speeches were so eloquent and persuasive that some called him a fraud, finding it difficult to believe he had ever been enslaved. To prove his claims, Douglass wrote his first autobiography, Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, An American Slave. Published in 1845, it made its author a celebrity. But fame brought with it the threat of capture, so Douglass embarked on a lecture tour throughout the United Kingdom in 1845. His devoted English supporters warmly welcomed him, ultimately negotiating and purchasing his freedom in 1846. Douglass was able to return to the United States a free man.

In addition to mastering oratory, Douglass understood the incredible power of the new medium of photography and how it could be used for political and social reform. The most photographed American man of the 19th century, Douglass was fully in command of his image, presenting himself as self-possessed, dignified and masterful, often gazing directly into the camera. “Douglass recognized the degree to which representation itself could be a powerful mechanism for ending slavery, for achieving universal freedom and equality,” said author John Stauffer.

Compared to his abolitionist peers, Douglass was an uncompromising and relentless campaigner for Black equality. Confined by white abolitionists to a narrow role of telling his story repeatedly to the public, Douglass broke away to express his own political ideas. He began publishing his antislavery newspaper, The North Star, in 1847. “To have a newspaper was to be the shaper of public opinion,” said historian Derrick Spires. “Founding the newspaper is sort of like Douglass’s declaration of intellectual and activist independence.”

He was an outspoken advocate—even a revolutionary—who insisted that ending slavery was necessary but was not enough to level the playing field. A fierce critic of President Abraham Lincoln for refusing to free enslaved people and allow them to enlist in the Union military, Douglass argued passionately that this action would end the war quickly. “Lincoln was a politician, so he was truly on the fence, and it would take somebody like Frederick Douglass, who I think Lincoln had great respect for, to say, ‘Mr. President, we can’t wait,’” said Kenneth B. Morris, Jr., co-founder and president of the Frederick Douglass Family Initiatives.

Finally, in 1863, after almost three years of war, the president issued the Emancipation Proclamation, authorizing the arming of Black men as soldiers. Douglass eagerly supported the effort and even recruited his two sons, who served in the first Northern Black regiment, the Massachusetts 54th.

Following the Civil War, Douglass was hopeful that the Union had been restored and alasting peace had been achieved. But he also knew that “if there is no struggle, there isno progress.” He spent the rest of his life continuing to work for Black equality.

Despite the extensive written and photographic record of his life, there remains much to be discovered about Frederick Douglass, both the man and his legacy. “Douglass is one of the most complicated people in our history,” said Columbia University’s Farah Jasmine Griffin. “He’s one of the few Black Americans—or Americans of any race—who left so much for us to read and engage with that he’s still, in some ways, directing us as we try to learn more about him.”

“Frederick Douglass moved from being a mirror to hold up to the nation about its failures to becoming a lens for future generations to understand their own public service, to understand their own commitment to justice, to understand why bravery is so important,” said historian Marcia Chatelain. “Frederick Douglass challenges us to become the fullest expression of ourselves and our ideals.”