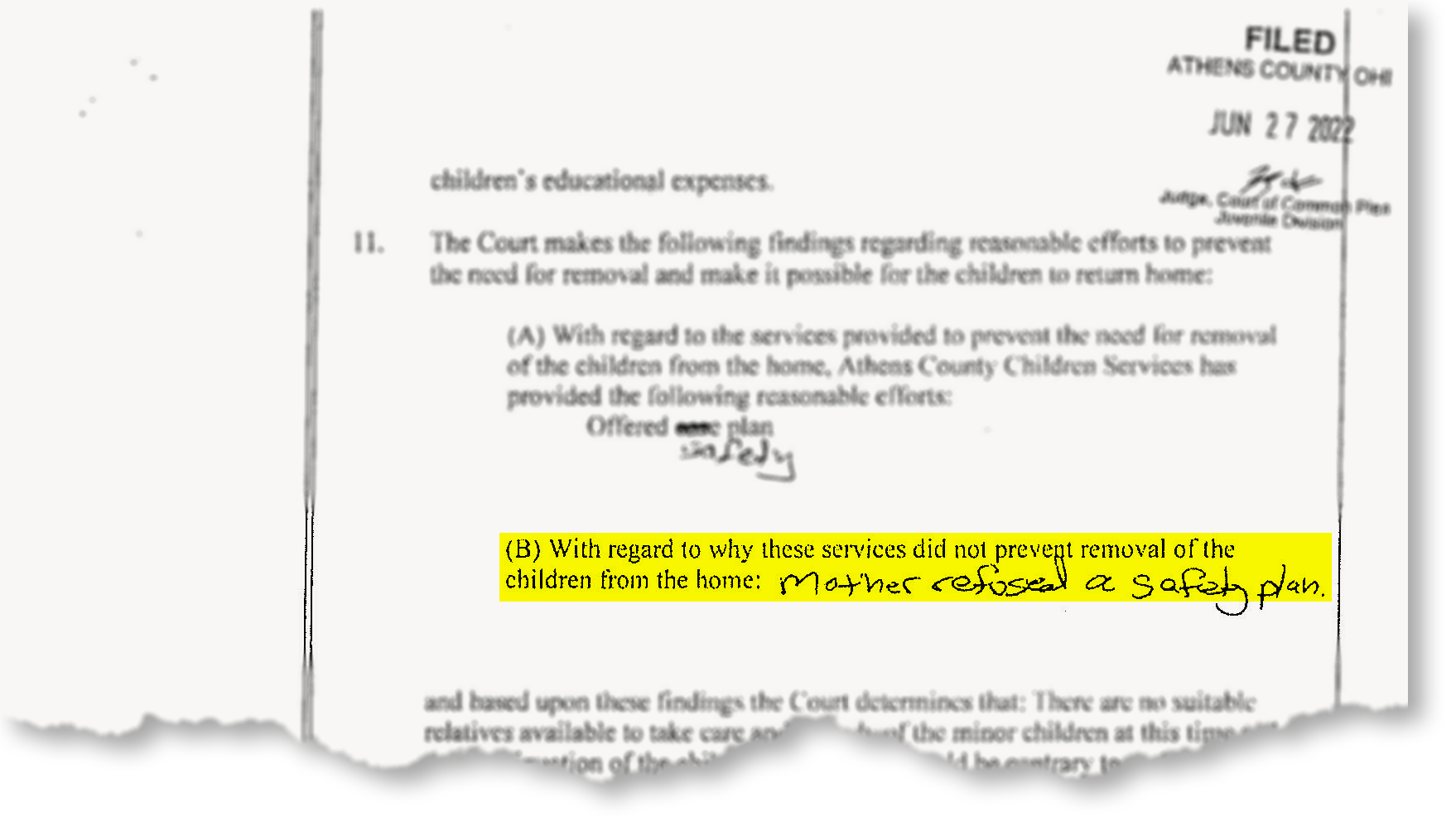

A court document indicates that efforts to prevent the removal of Theresa Fogel’s children were unsuccessful because she refused the safety plan she was offered.

Chapter 2

The safety plan

Two days after driving off with Theresa Fogel’s four children, caseworker Jacelyn McGaughey was asked in court what steps she had taken to avoid removal.

Removing children from their parents is supposed to be a last resort.

“I spoke with Theresa and I offered a safety plan,” McGaughey told the judge. Theresa refused it, she said, and drove off with her daughters.

Theresa insists she didn’t know who McGaughey was when the caseworker showed up at her home.

“That’s a safety plan, when you don’t even introduce yourself, tell me who you work for? Nothing?” Theresa said.

The plan McGaughey offered was to take Theresa’s children and place them with relatives or in foster care for a while.

This may sound like a removal, but under a safety plan it’s voluntary. The parent is agreeing to let their children stay somewhere else for a while. It’s an effort to avoid getting a court order to take the children.

But this legal distinction was lost on Theresa, as it would likely be for many parents.

All she heard was McGaughey wanted to take her children out of her home.

Not only did Theresa not know she was being offered a safety plan, she didn’t understand the consequences of refusing it: McGaughey got an emergency court order to remove the children into the custody of Athens County Children Services. It was no longer a voluntary process.

It wasn’t until weeks after her children were removed that someone explained to Theresa what a safety plan is. She repeatedly asked Children Services for a copy of the plan McGaughey said she refused, but never received one.

That’s likely because the plan was not written down.

But the safety plan, and what it meant, should not have come as a surprise to Theresa. It’s supposed to be developed with input from the parents. And it’s supposed to be written and signed by the parents.

First, a safety assessment

Removing children from their parents is one of the most difficult decisions caseworkers have to make. No one in the system wants to see children suffer because they were left in an abusive or neglectful home. At the same time, research and experience show removal is traumatic and can have lasting consequences.

The decision is not the caseworker’s alone. It involves a team of people at the agency that includes the caseworker’s supervisor, the prosecuting attorney assigned to the agency and other staff, said Matt Starkey, public information officer for Athens County Children Services. And the agency can only recommend removal. It’s up to a judge to give the order.

Under Ohio law, children can be removed from their home only when it’s necessary to prevent immediate or threatened physical or emotional harm.

The first step in that process is a safety assessment.

After hearing what Theresa’s boys had to say at the library, a caseworker’s next step would be to go to the home and do a safety assessment, said Diane DePanfilis, a professor of social work at Hunter College in New York City. DePanfilis is intimately familiar with child welfare investigations. She wrote the latest edition of the federal government’s guide for caseworkers and co-wrote the previous two editions.

Safety assessments are required under state law. They should be done before a safety plan is developed, because the assessment helps determine whether a safety plan or some other intervention is the best approach — or if any intervention is necessary.

Ohio law requires that a safety assessment be completed to determine the appropriate response when there are concerns about a child’s welfare.

DePanfilis said the assessment would include talking to the parents and possibly others in the home in an effort to verify the allegations. Even in a situation in which a child says a parent or someone else in the home has threatened to kill them, she said, the caseworker should take some time to investigate before taking action.

The assessment also determines whether what is being alleged is a one-time situation or an ongoing problem. This includes a deeper look into how the family functions, the overall parenting practices, and whether the parents have the capacity to address the threat and keep their children safe.

Kelli Jelinger, a public defender in Erie County who specializes in child removal cases, offered this scenario: “So they come to the house, ding, ding, ding. I’m Susie from (children services). We have some concerns. These are the concerns that we have. We need to investigate those. They spend a half hour, an hour asking questions, looking around the property, talking to people, right?”

This is not what happened in Theresa’s case.

After the assessment, the caseworker shares this information with the review team. This is the initial check in the system and helps determine what the next steps are and whether the situation justifies removal, if that is being considered. The team does not simply take what the caseworker says at face value, Starkey said.

“There’s questions,” he said. “And so these are very intense where the caseworker is, for the first time in the case, which probably won’t be the last time, is put on the stand … in front of their coworkers, their supervisors, the director, the deputy director. And they’re being told to describe the situation. They’re being asked questions about the situation. And it’s all in an attempt to get the facts, the actual facts of the case together. Because we don’t want to get to court and find out that a caseworker lied to us. We want to get to court and have all of the facts available so that we can give our best case in front of the judge.”

Coming up with a plan

Whether removing children is truly the last resort depends largely on the thoroughness of the safety assessment. It determines whether there are significant ongoing risks to leaving the children at home and what steps, if any, can be taken to address the risks without removal.

The law requires that reasonable efforts be made to avoid removing children from their home, and the safety assessment is an integral part of this process.

If the assessment shows a child is in immediate danger of serious harm because of an active safety threat, the agency is required to develop and implement a safety plan. This identifies steps that need to be taken to address the threats.

Depending on the plan, the children might stay at home or they might be placed with relatives or in foster care for a while. In either case, the plan is voluntary and doesn’t involve the court system. That’s a huge difference for the family.

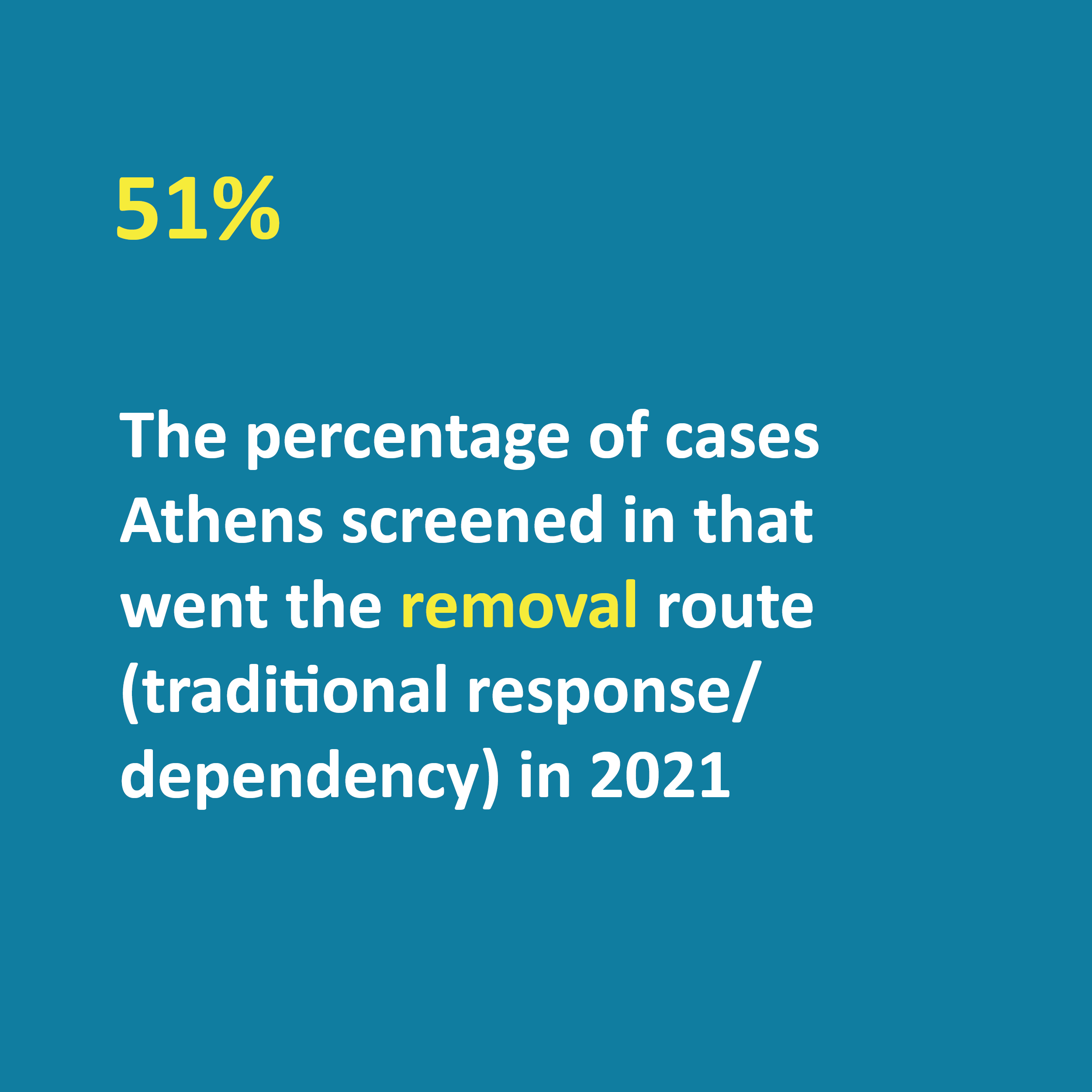

When children are forcibly removed under a court order, the agency is taking custody of them. This sets in motion a lengthy court process and can result in significant restrictions on parents’ ability to see and interact with their children. It can take several months or even a year or more for parents to get their children back.

But if a safety plan doesn’t resolve the problem — for example, because the parent refuses to participate in the plan or agrees to the plan but doesn’t follow it — the agency can move on to a court-ordered removal.

Ohio law requires a safety plan be developed if an assessment determines a child is in “immediate danger of serious harm due to an active safety threat.”

The safety plan is supposed to be developed with input from the parents. It is supposed to be recorded on a form created for this purpose. And parents are supposed to sign the form, indicating their willingness to follow the plan.

In Theresa’s case, the only allegations that could reasonably be construed as placing the children in immediate danger of serious harm are that Theresa’s live-in boyfriend, Tyler Tingley, swung a hammer at her older son, Josiah, and threatened to get a gun and shoot him.

It’s not clear whether or to what extent McGaughey, the caseworker, did a safety assessment before turning to a safety plan. If an assessment was done, it seems it did not include talking to Theresa or Tyler or checking out the home in at least a preliminary attempt to try and verify what the boys said. Theresa and Tyler both said that no one from the agency talked to them about the allegations.

Barbara Cline, a member of the management team at Athens County Children Services, mentions a safety assessment in a response to Theresa’s repeated requests for a copy of the safety plan.

“There is no safety assessment document to provide to you,” Cline wrote in an email sent Aug. 25, 2022, two months after Theresa’s children were removed. “When the case was initiated the caseworker spoke to you about doing a safety plan to allow time for everyone to calm down and for the situation to be assessed. No plan was developed as it was noted you did not wish to do a safety plan.”

Cline’s wording suggests some kind of assessment would have come after the safety plan. A safety assessment should come first, according to state law. And if the assessment leads to a safety plan, the purpose of the plan is to address the concerns raised by the assessment, not to buy time for an assessment to be done later.

Cline notes in her email that the caseworker spoke to Theresa about doing a safety plan and that no plan was developed.

This is what McGaughey said about the safety plan in court: “I stated that the boys have said that Jamie, the aunt, is a suitable relative that we could look at for a safety plan. And she stated she did not wanna do a safety plan and would rather the children go into foster care. And I explained to her that it would be all four children, not just the oldest two. At that point she refused to do any type of safety plan, took the younger two and they fled the home in her vehicle.”

It does not appear, based on McGaughey’s testimony and Theresa’s account of what happened, that McGaughey showed up at Theresa’s home to work with her on developing a safety plan — which might or might not involve removing the children from the home, and would also include what other steps needed to be taken to address the safety threats. Instead, it seems a decision had already been made that the plan was to remove the children from the home. It was just a question of where they would go.

If so, this doesn’t sound like a safety plan as detailed in state law or in the instructions for completing the required safety plan form. The form includes this unambiguous guideline: “The parents or caregivers are an integral part of the safety plan and should have a prominent role in its development and implementation.”

McGaughey was not available for an interview for this story. Even if she was, confidentiality rules would prohibit her from discussing the details of a particular case. The records in these cases are also confidential.

WOUB provided Athens County Children Services with a detailed list of what the story would include about Theresa’s case and asked the agency to highlight anything that was incorrect. The agency responded that its confidentiality rules prevented it from doing this as well. It provided a statement from Executive Director Otis Crockron:

“I fully stand by the work my caseworkers, supervisors, managers and staff perform daily in difficult and stressful circumstances. Athens County Children Services caseworkers are required to go through extensive and continual training and supervision to ensure that they perform to the best of their abilities and in accordance with ORC (Ohio Revised Code) guidelines and the norms and practices of our court system. Our team-based agency decision making model provides the framework to ensure that any recommendations from our caseworkers have gone through rigorous examination and evaluation before they gain the full weight and backing of Athens County Children Services.”

What happened with the safety plan in Theresa’s case may not be all that unusual.

Kelli Jelinger, the Erie County public defender, and Denise Ferguson, a public defender in Cuyahoga County, have spent their careers representing parents in child removal cases. Both have handled cases where caseworkers show up at a home with a safety plan already in mind that involves removing the children and placing them with relatives or in foster care for a while. And they don’t always explain to parents that the consequences for refusing could be a court order to take their kids into the agency’s custody.

“What they do,” Ferguson said, “is they go out to a house and a lot of times they go back and tell the supervisor, ‘But you know, she wouldn’t talk to me.’ ‘OK, well the children are in danger because we don’t know that they’re not, so let’s file in court.’”

Jelinger said defense attorneys can argue in cases like Theresa’s that what the caseworker presented doesn’t really constitute a safety plan because there was no assessment of the family or participation from the parents in creating the plan. The defense also can argue that refusing to agree to what is being presented isn’t really a refusal of the safety plan if the parents don’t understand what’s going on.

“She doesn’t know what you’re here for,” Jelinger said. “That is her responding, saying ‘You’re not taking my children’ to a woman who shows up and without any sort of evidence, without any sort of explanation, without any sort of on-the-spot investigation, questioning, answering, you know, talking to me, says you’re gonna take my children? The hell you are. You better come at me with more than, ‘If you don’t do this I’m taking your kids.’ But they call it a refusal.”

A crisis on two fronts

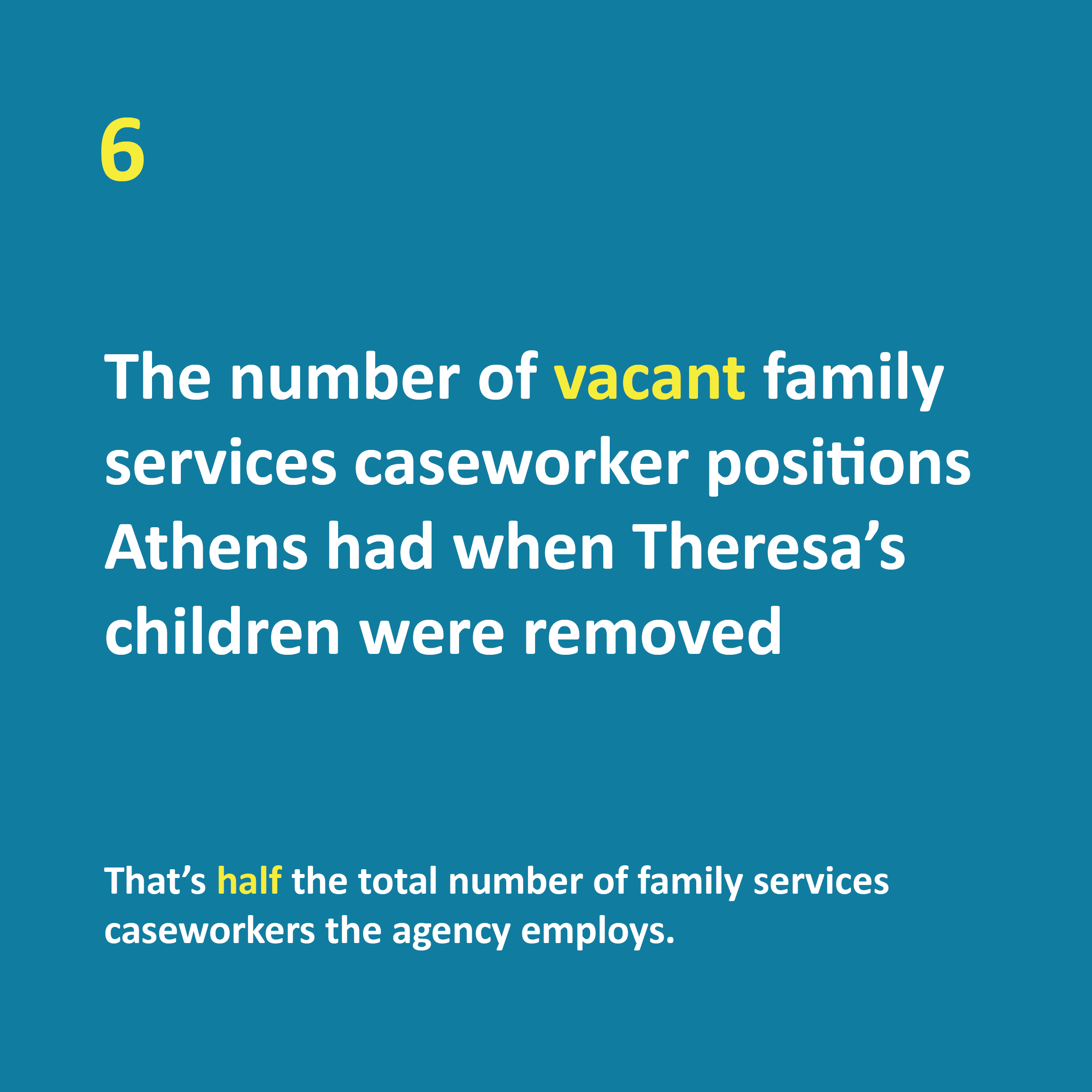

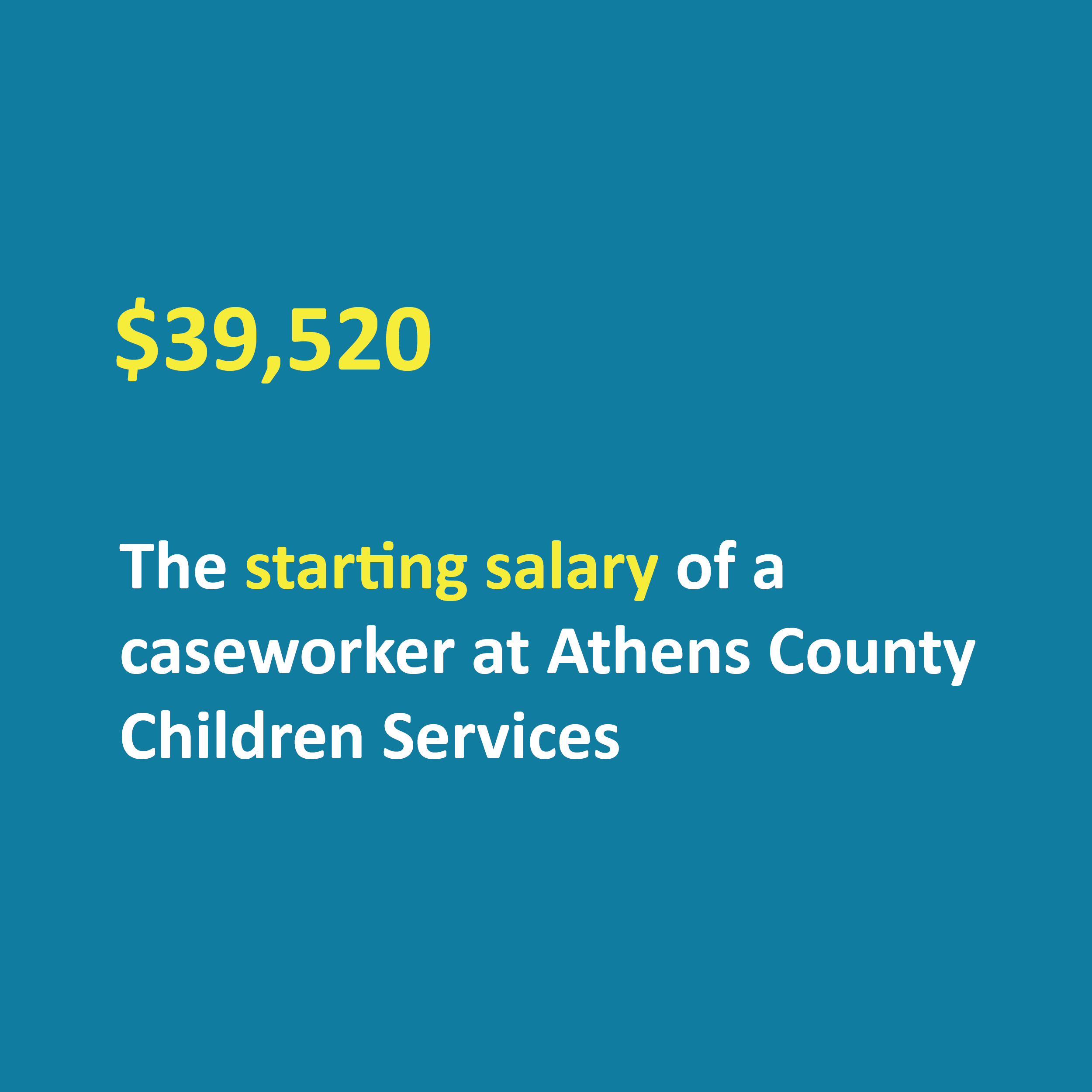

Ohio’s child welfare system is struggling with a workforce and placement crisis. The system is overwhelmed with cases it doesn’t have the staffing or in many cases the expertise to handle.

This can result in children being removed when there are other and better options, which only increases the burden on the system.

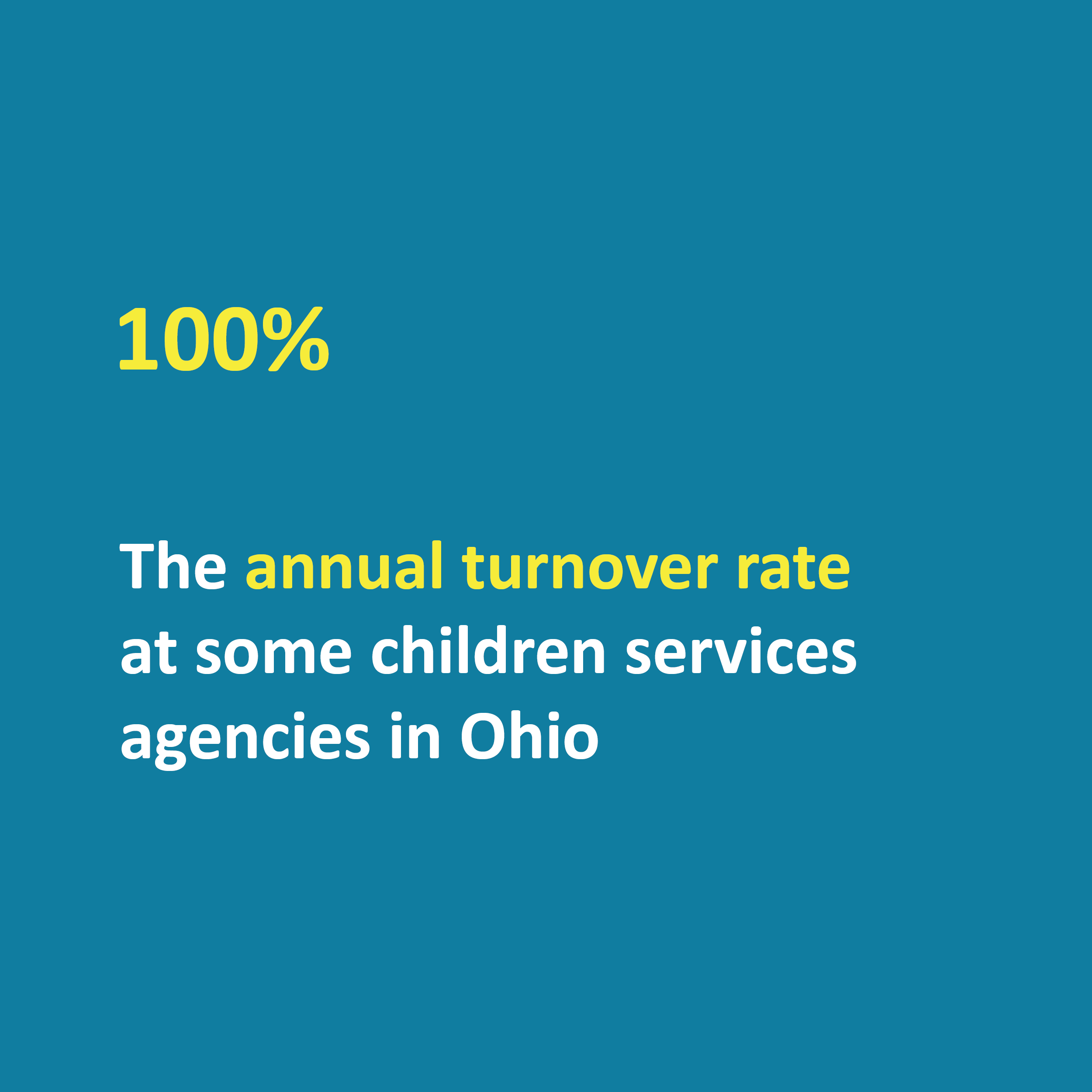

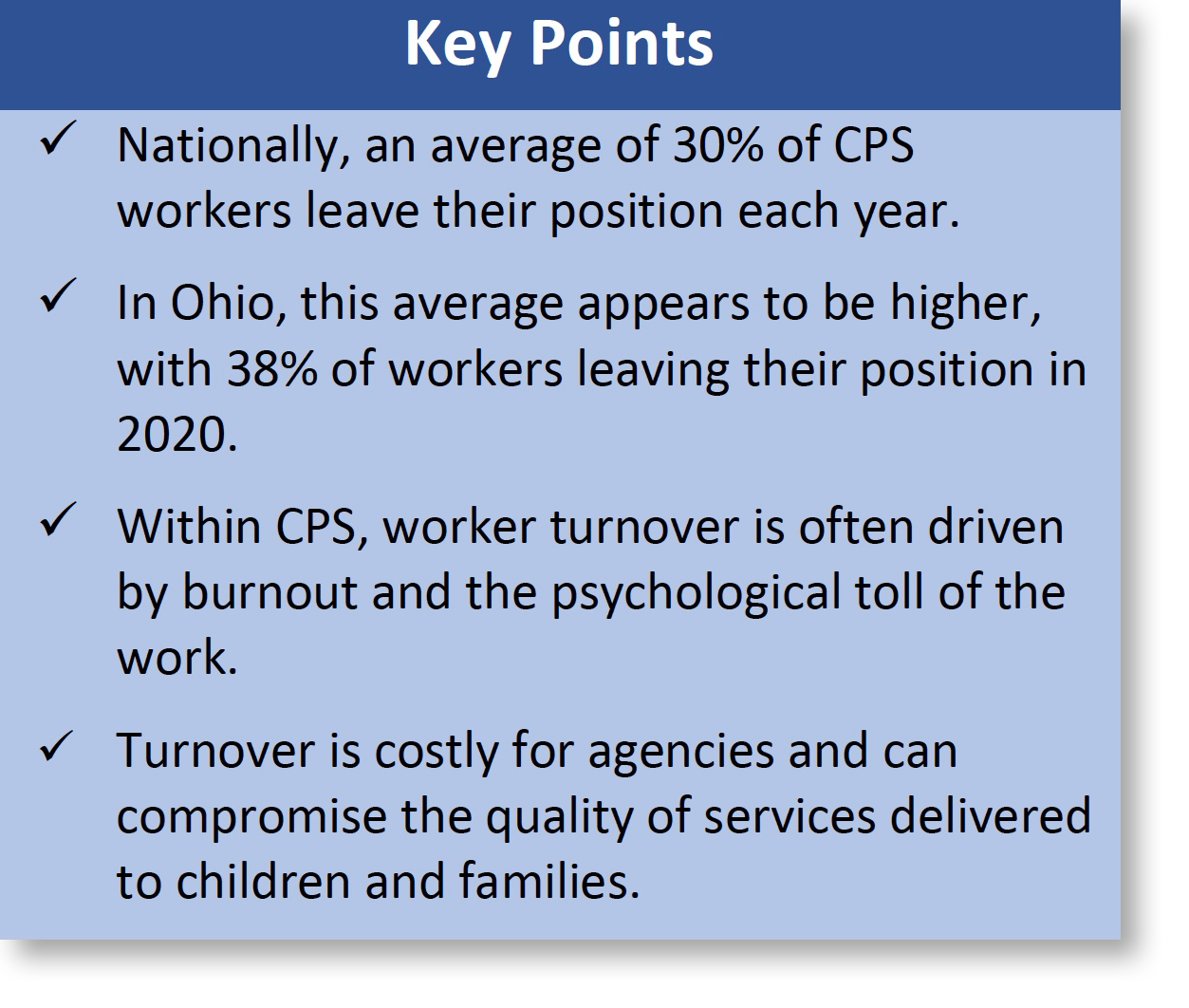

Children services agencies nationwide have been dealing with high rates of turnover for years, especially among caseworkers. A February 2022 workforce report based on a study by researchers at The Ohio State University found high levels of stress and burnout for caseworkers.

The caseworker turnover rate in Ohio nearly doubled from 24 percent in 2016 to 45 percent just three years later in 2019, according to the report. The rate dropped to 38 percent in 2020, during the onset of the pandemic. More recent figures are not available to show whether that dip in turnover was related to the pandemic.

Children services agencies in some Ohio counties have had years where their turnover was more than 100 percent.

A graphic from a report by researchers at The Ohio State University details some of the workforce challenges faced by child welfare agencies.

These high turnover rates result in cases taking longer to work through the system and longer stays in foster care for children. This creates more trauma for families and for caseworkers, who end up with higher caseloads when their agencies are short-staffed.

The workforce report cited studies that have found that more than half of Ohio’s child welfare workers experience levels of stress that meet the threshold for post-traumatic stress disorder.

“So they’re seeing many of the same levels as returning veterans and other folks who experience a lot of trauma on their jobs, and that’s also leading to the turnover that we’re seeing,” said Scott Britton, assistant director of the Public Children Services Association of Ohio.

“Our caseworkers are really dealing with a lot,” he said. “I mean after the Great Recession we’ve had 10 years plus of an addiction epidemic, started as an opioid epidemic, but in many ways our caseworkers became first responders. Sometimes they were first on the scene of an overdose and were administering naloxone or telling a child in the next room that their parent was incapacitated.”

High turnover also means that more cases are being handled by young and inexperienced caseworkers.

“That’s why our workforce crisis is so damaging, not just for our agencies but really for children and families,” Britton said, “because it means that we have 22-year-old college graduates put in situations where they are having to follow a very complex assessment and planning model, think on their feet, be aware of hundreds of different Ohio administrative code rules that govern their work, and make a decision that could impact this family for a lifetime.

“When ideally we would have folks who come into our system, stay, gain experience, really develop their critical thinking skills, and are making those judgments from a place of having done this hundreds of times before and feeling very comfortable with it.”

Britton attributes some of the high burnout and turnover to a misunderstanding of what caseworkers do. His organization is trying to make it clearer what the job is about.

“It takes a specific calling to be a children services caseworker, and it takes persevering through that calling,” said Matt Starkey of Athens County Children Services. “Some people get here thinking that they’re working with kids. You’re working with families. That’s the thing. And so we try to be very upfront with all of the caseworkers as they come on board, saying it’s tough.”

Athens County Juvenile Court Judge Zach Saunders has witnessed the burnout in his courtroom. He acknowledges reforms are needed within the child welfare system, but this requires the efforts of caseworkers and supervisors who stick around long enough to make the changes happen.

“I’ve seen ones that have been go-getters trying to change the system, and they’re done within a year. I’ve seen ones that were done in two months,” Saunders said. “And it’s sad because we need people like that.”

Nowhere else to go

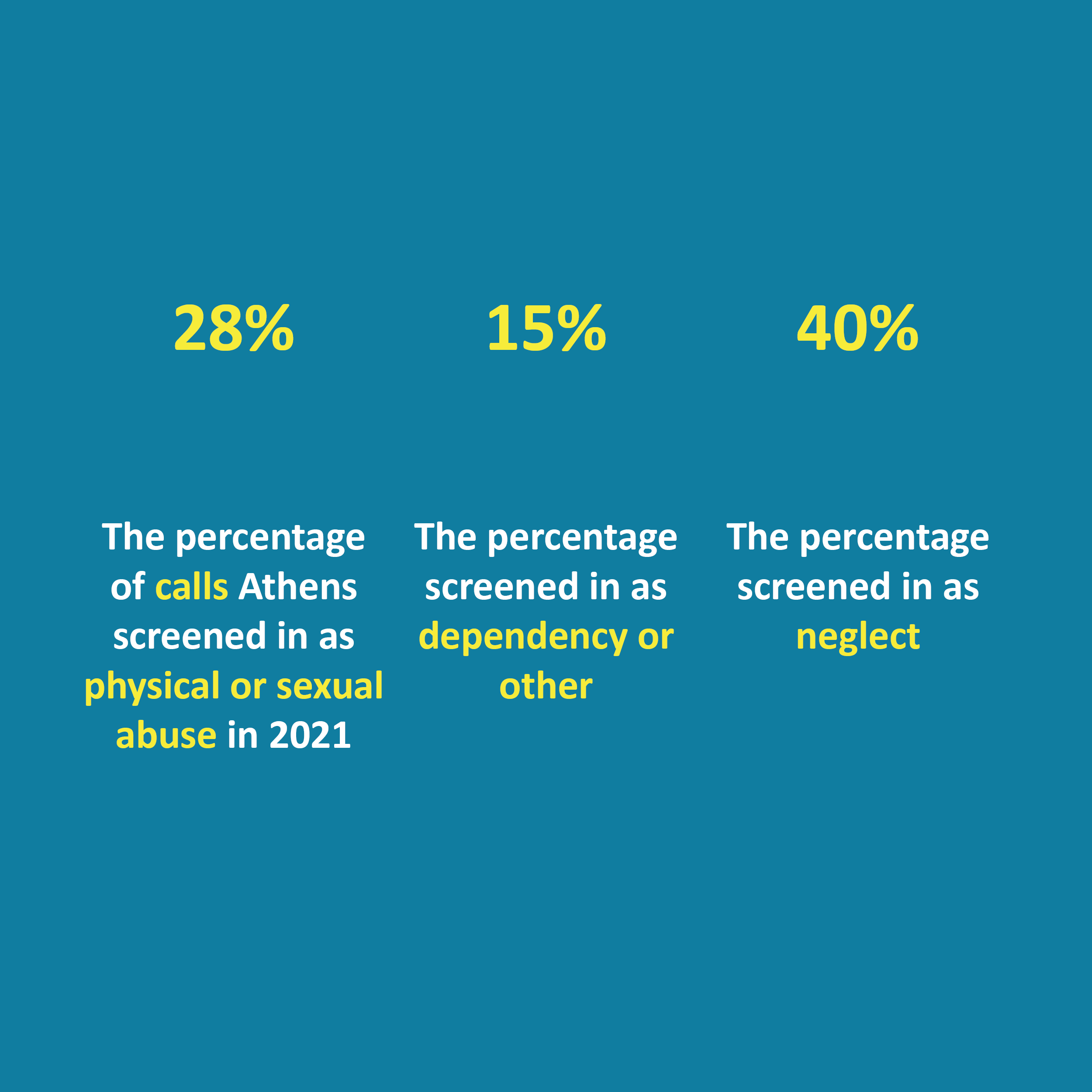

As they struggle to find and retain staff, Ohio’s children services agencies field hundreds of thousands of calls a year.

Some come from concerned family members, friends or neighbors. Many come from mandatory reporters, who are required to report if they know or suspect child abuse is occurring. These include doctors, nurses, teachers, child care workers, lawyers, psychiatrists, members of the clergy and social workers.

Each report goes through a screening process where the agency has to decide, sometimes based on very limited information, whether to further investigate.

Once a case is screened in, it must be investigated no matter how overworked and understaffed the agency is, Starkey said. If it’s an emergency, he said, a caseworker must be out within an hour to investigate.

“We can’t just say, ‘No, we’re too busy now. Next one, we’ll take the next one,” he said.

Most screened in cases involve reports of abuse and neglect. These are the cases child welfare agencies are primarily designed to handle, said Scott Britton of the Public Children Services Association of Ohio. Plus, there’s an argument to be made that an agency with the power to take children from their parents should only be getting involved in the most serious cases.

“Children services has always been that kind of arbiter of civil liberties, right?” Britton said. “Parents have the right to raise their children the way they see fit. And the public interest is when there is abuse or neglect, and so there should be a high bar for sending somebody from the government out to knock on a door and interfere in a family’s life.”

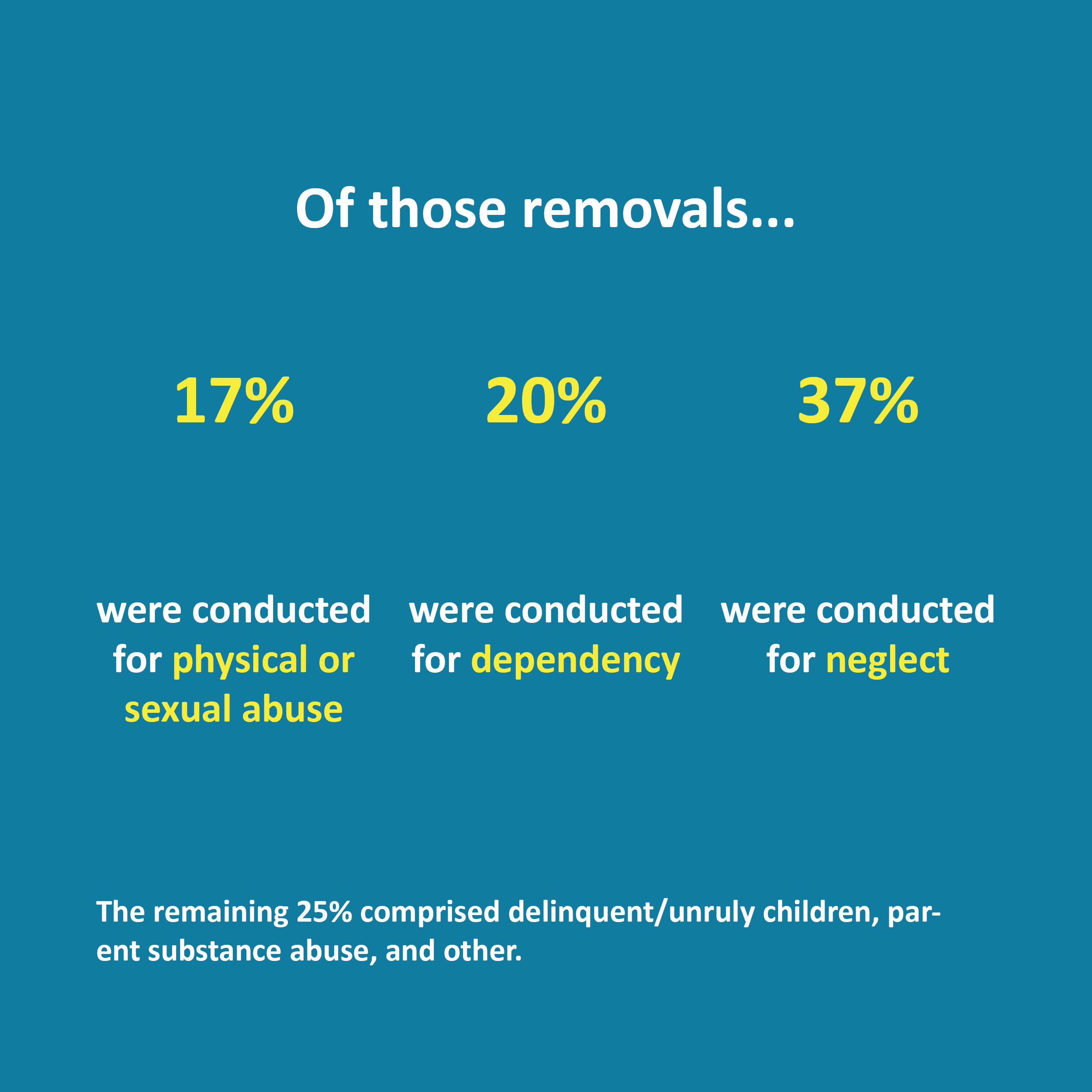

But a significant number of removal cases do not involve abuse or neglect, according to state data. And the agencies end up taking custody of children with needs they are not best equipped to address and who would be better served elsewhere, Britton said.

For example, a report last year found that hundreds of children in the custody of children services agencies end up there primarily because of behavioral health needs or developmental/intellectual disabilities. One of the primary reasons is there are no alternatives in the community for them.

Finding appropriate placements for these children diverts considerable time and resources away from the abuse and neglect cases.

The Public Children Services Association of Ohio, which prepared the report, says the agencies are dealing with a placement crisis.

A report by the Public Children Services Association of Ohio finds the state is dealing with a placement crisis driven in part by a lack of community resources to help families.

“These families are coming to children services because there is nowhere else for them to go,” Britton said. “And that is another complicating factor that increases our caseloads for our very much reduced workforce that then can lead to decisions being made that tend to side toward, ‘Let’s get that child to a safe place so that I don’t have to worry about leaving them in what could potentially be a dangerous situation.’”

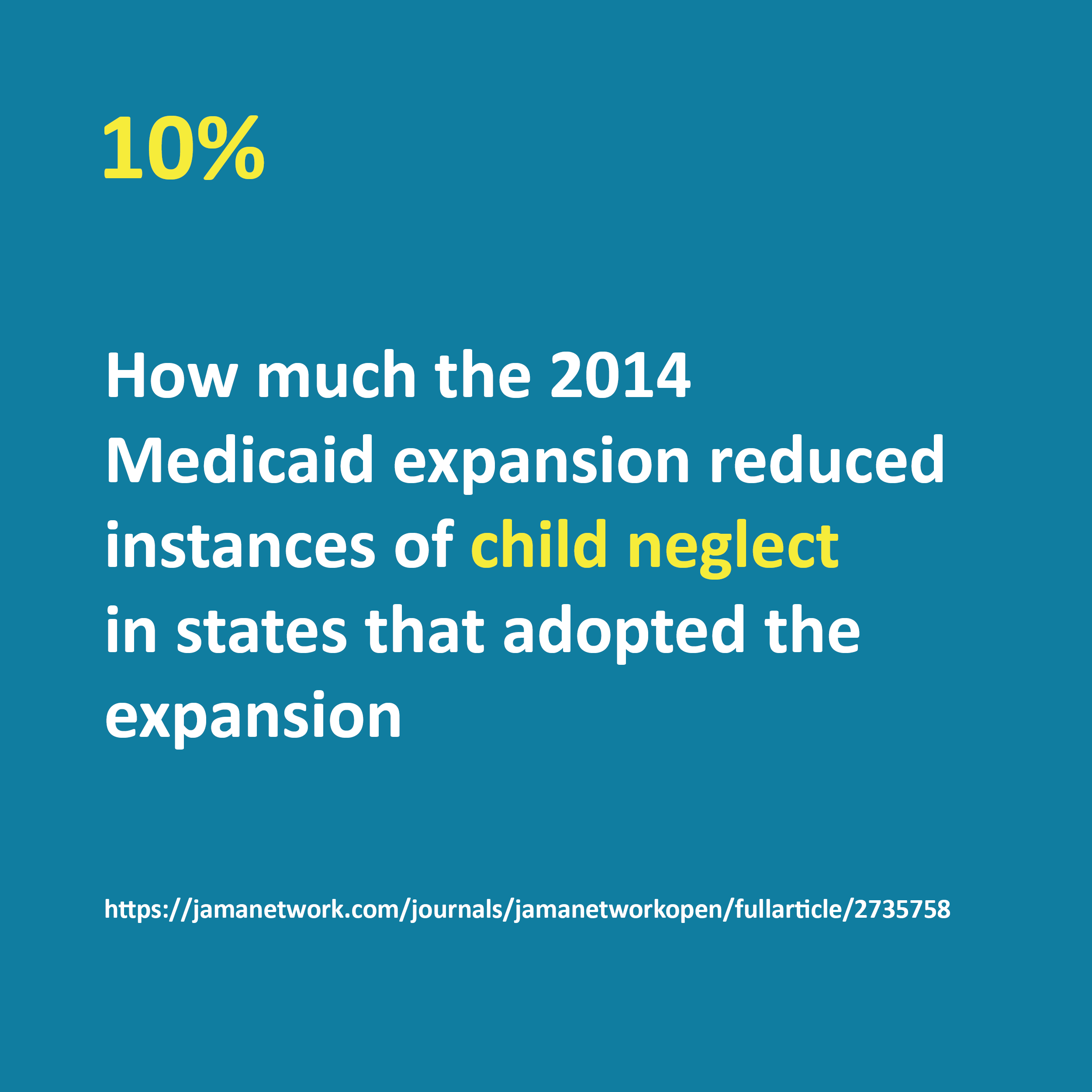

The solution to the placement crisis requires more services available in communities to provide families with mental health support, addiction treatment, parenting education and other interventions to address the underlying problems before these families wind up at children services agencies, Britton said.

Those services require substantial investments of government funding and some kind of coordinated system to identify families in need to connect them with the appropriate services.

“We need all of that and we needed it 10 years ago,” Britton said. “But in the meantime, children services has tried to fill the void, and we’re not good at it.”

Path of least resistance

A little more than a year before Theresa Fogel’s children were removed, a young woman who had run away from home wrote a long Facebook post detailing years of sexual abuse within her large Athens County family.

The investigation that followed confirmed the woman’s reports. Her parents ended up in prison and two of her brothers pleaded guilty to felony charges. It turned out that several reports had been made to Athens County Children Services about the abuse, but the cases were closed with little investigation.

It’s cases like these, in which children services agencies do not remove children who are suffering serious abuse or neglect, that make the headlines.

These stories focus public attention and outrage on the agencies and caseworkers, with accusations that they miss, downplay or ignore warning signs, and that they don’t move swiftly enough to get children out of dangerous homes. This creates pressure for new laws and policies that encourage more removals.

This pressure is felt by those working in the system. No one wants to be blamed for the death of a child because they decided not to remove.

“That’s something that unfortunately is always in the back of your mind,” said Zach Saunders, the Athens County judge. “But I don’t let it consume me because I have to do the right thing. It’s a hard thing to swallow, and that’s a tough thing about this job. But I can’t just say that that child can’t go home because something has happened in California in the past. That doesn’t necessarily mean that that’s gonna happen in this case. But again it’s a balancing act, and it’s tough.”

Athens County Children Services, like child welfare agencies nationwide, is dealing with a combination of higher caseloads and a staff shortage. [Theo Peck-Suzuki | WOUB/Report for America]

One popular argument is if the system is going to err, it should be on the side of removal. When agencies have to make a difficult call, better to remove some children who may have been better off left at home than to not remove children who may end up seriously abused or dead.

“That’s what this system is,” said Denise Ferguson, the Cuyahoga County public defender. “The safety of the kids is more important than anything else, regardless of how speculative it may be.”

Ferguson and others argue that what this approach ignores is the harm removal itself causes children.

“What the public doesn’t understand is for every child death, there are thousands of kids in foster care that shouldn’t be there and don’t need to be there,” said Jennifer Renne, director of courts projects for the American Bar Association’s Center on Children and the Law.

Renne used to represent families in removal cases and has written three books about the child welfare system, including a guide for attorneys and judges who work in it. She now provides training for attorneys and judges around the country on how to make the system work better for children.

“We always say remove the danger, not the child,” Renne said. “And sometimes the path of least resistance is to remove the child” before there’s been an assessment of the safety threats and an attempt to address them.

The death of a child who should have been removed but wasn’t is without question the worst possible outcome. Renne and others note that these cases are rare.

What the public doesn’t see is the damage removal can do to children, which even those in the system acknowledge can be worse than the abuse they suffered at home. It’s rare that cases of unnecessary removal and the impact on the children make the headlines, making it difficult to draw attention to the issue.

“The only time generally people know about this system is a situation in which a child ‘known to the system’ has died some horrible death,” said Richard Wexler, executive director of the National Coalition for Child Protection Reform. “And then you find out, because it’s one of the few things they can’t keep secret, that the case file had more red flags than a Soviet May Day parade. So, everybody thinks how in the world could that have happened? So, the knee-jerk response is the system must be bending over backwards to coddle those horrible, abusive parents.”

Wexler and others argue the underlying problem is that child welfare agencies are overwhelmed with too many cases where removal was not the right approach, draining time away from more thorough investigations into cases where the evidence would reveal a child should be removed.

“So long as agencies are running around spending scarce resources on these cases that don’t belong on their docket or in juvenile court, they’re gonna miss the horrific cases,” said Vivek Sankaran, a University of Michigan Law School professor and national expert on the child welfare system.

For those who work in the system, caseworkers are often seen in a no-win situation when it comes to removals, making difficult, high-stakes judgment calls for which they will be criticized whatever they decide.

“Most people aren’t happy with children services no matter what we do,” said Scott Britton of the Public Children Services Association of Ohio. “We either do too much or we do too little.”

Wexler argues that while this may be true, the consequences of making the wrong call only flow in one direction.

“I have followed this field now for more than 45 years, first as a reporter, now as an advocate,” he said. “In all that time I have never seen a caseworker fired, suspended, demoted or so much as slapped on the wrist for taking away too many children. All of those things and more have happened to workers if they leave one child in a home and something goes wrong.

“So, when it comes to taking away children, workers are not damned if they do and damned if they don’t. They’re only damned if they don’t. … All the incentives push toward taking away the children. None push the other way.”

The challenge for Wexler and others who want to reform the system is building public and political momentum behind reforms that would reduce the large number of child removals and the trauma this causes — something almost invisible to the public because the system operates behind a wall of confidentiality.

Meanwhile, the consequences of just one case where a child wasn’t removed can be severe and highly visible, instantly draining support for reform.

“Unfortunately for many of my fellow liberals, if you want to get them to forget everything they claim to believe in about civil liberties, just whisper the words child abuse in their ears,” Wexler said.

“You would never see the left say, well it’s OK to have massive stop and frisk because you just might stop a crime,” he said. “And yet we have vastly worse intrusion into families, mostly the same families — poor families and nonwhite families. … Now, there are some very good people on the left and right who get this. It took the worst of left and right to create the system. It’s going to take the best of each to change it.”