150 days

Children Services took a mother's kids after her teenage son reported her.

Much of what he said was never proven.

But that didn't seem to matter.

Theresa Fogel stood in her neighbor’s driveway with the deputies and watched as her two young daughters were loaded into the car. Her two sons were already in the vehicle. A few minutes later, they were gone.

She didn’t know why her children were being taken from her. And she didn’t know when she would see them again.

It was one month to the day since she had moved her family from the outer suburbs of Cincinnati to Glouster, a rural village in the heart of Ohio’s Appalachian region.

Theresa said she was drawn by the area’s natural beauty. It seemed like a good place to leave behind the troubles that had been tearing at her family and build a new life.

From the moment they arrived, things had not gone as planned.

Still, Theresa was trying to make the best of it, confident that beyond these initial setbacks, a better life was within reach.

And now this.

“I came here for a fresh start and to get out of a city, to get my kids away from all that crap,” Theresa said. “I came here, and then my life has turned into a complete nightmare.”

Most stories about child removal focus on when an agency should have removed children from their homes but didn’t. The consequences in these cases are often devastating, involving serious physical harm, sexual abuse and death. These are the cases that make the headlines, stir public outrage, create political pressure and may drive those in the system to err on the side of removal.

Critics of the system say cases in which children are removed when they should not be are far more common. In many cases, this happens for reasons that have more to do with being poor than bad parenting.

While these cases rarely make the news, they too can have devastating consequences for both children and parents. Critics say that even when conditions at home raise concerns about the welfare of the children, it often would be better for the children to keep their families together and connect them with services to help address the concerns.

For eight months, WOUB reporters David Forster and Theo Peck-Suzuki followed Theresa’s case. It provided a rare window into a system that is largely closed off from the public.

They interviewed dozens of people both within and outside the system to understand how it is supposed to work, what checks and oversight are built into it, and what changes could improve it.

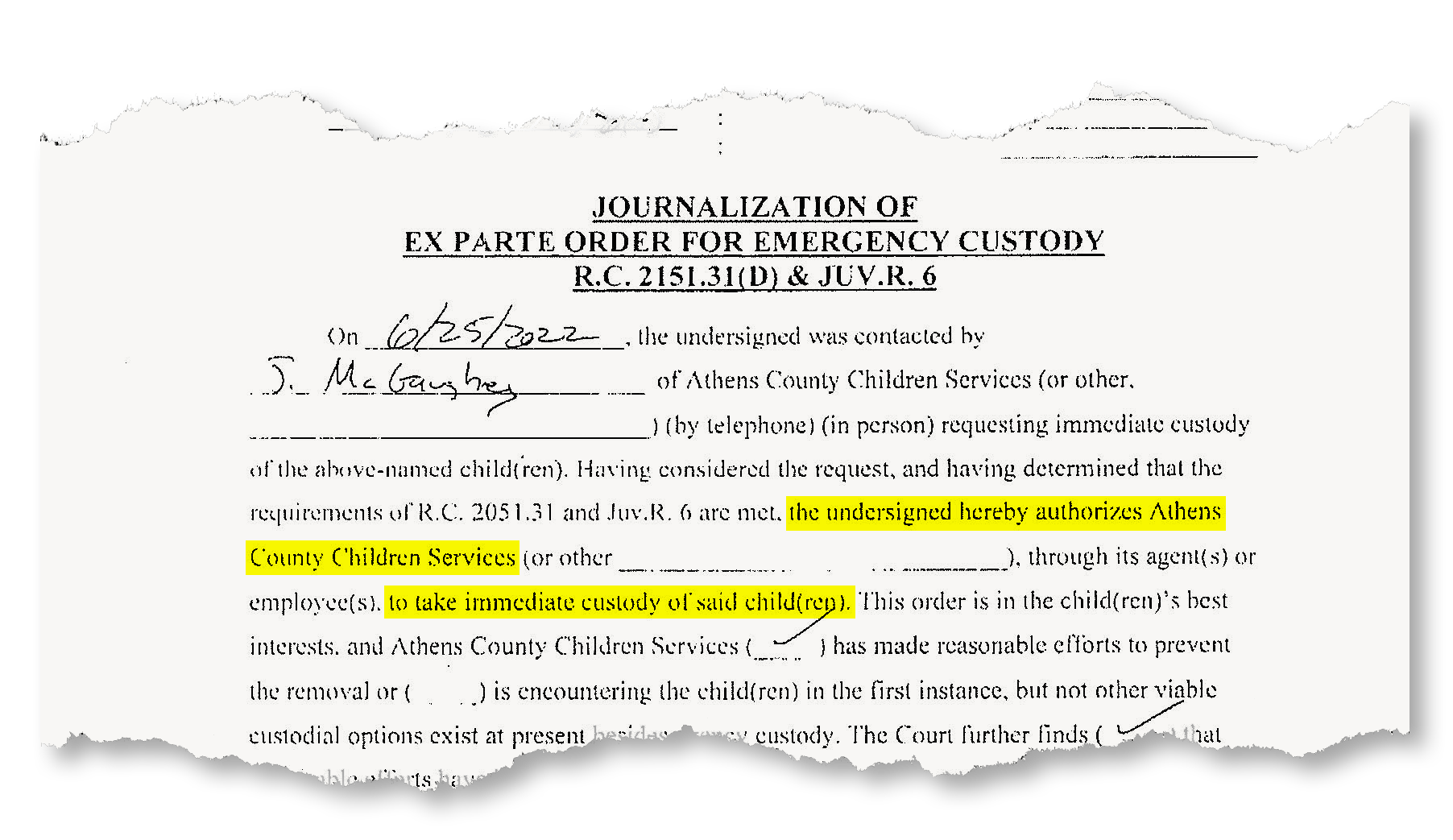

Theresa’s children were removed under an emergency order because a caseworker with Athens County Children Services believed they were in danger. The caseworker said her decision was based on serious allegations made by Theresa’s two sons, in particular the older son, who was not happy about the move to Glouster.

Most of the allegations were either untrue or lacked evidence to support them. The few that were true did not justify removal, according to the agency’s own policies. But that didn’t seem to matter as her case moved through the system.

The judge overseeing Theresa’s case acknowledged that if children are taken from their home based on false accusations, it can still take at least a month for parents to get them back. This is in part because the investigations and the hearings and the rest of the process takes time, especially in a system overburdened with cases.

Another reason is that it simply may not matter whether the allegations against parents are true because the agency will never have to prove them and justify the removal.

That’s just the way the system works.