Communiqué

Albany Man Offers Rides and Stories to Moonville Tourists

By: Tim Sharp

Posted on:

On most Saturdays between July and November you can find John Hutchison hitching his team of Percherons to his 20-passenger wagon for trips to what many believe to be the haunted Moonville Tunnel.

It’s hot for a May evening – in the 80s. A bit muggy as we roll into the parking lot behind the one-room Hope School House near the town of Zaleski in Vinton County. About 20 paying customers take their seats on upholstered benches on either side of the wagon.

He stops the horses in the shade where he introduces himself – and his team. A young girl riding shotgun correctly answers Hutchison’s question about the type of horses pulling the group. They’re named “William the Conqueror” and “Richard the Lion Hearted,” he said.

“But that’s too big a names for little horses like this so we call them Dick and Bill,” he tells the group.

Hutchinson’s wife Teresa follows in a Jeep.

“We get a long ways from civilization back here and there’s no cell phone service and I like to have a car around,” he explains. “I’ve never needed it yet, knock on wood.”

The round-trip to Moonville and back will take just over three hours. On the way Hutchison shares some history of the area and details about the train that roared through these hills.

“There was a stagecoach route there and it was the trail connecting Marietta with Cincinnati and in the early settlement of Ohio; Marietta and Cincinnati were two pretty important towns so it got quite a bit of use,” he begins.

He tells of a donut-shaped Indian burial mound back in these hills that caught the attention of one of his passengers, an archeologist with the Wayne National Forest. But the donut shape was not the original design of the builders.

“About 90 percent of the donut-shaped Indian mounds are just ordinary shaped Indian mounds that someone dug up and they left the outside edge,” Hutchison explained.

But the feature attraction of the trip is his ghost stories, which he qualifies with a statement of disbelief.

“I’m a fundamentalist Christian and my world-view does not allow for disembodied spirits of those who have died to be floating around here – I can’t reconcile that with what I believe to be true,” he said.

But he does acknowledge there is something generating the interest in the Moonville Tunnel.

“I do think that people see something; now what the something is I don’t know but I don’t think it is the spirit of people who have died,” he said.

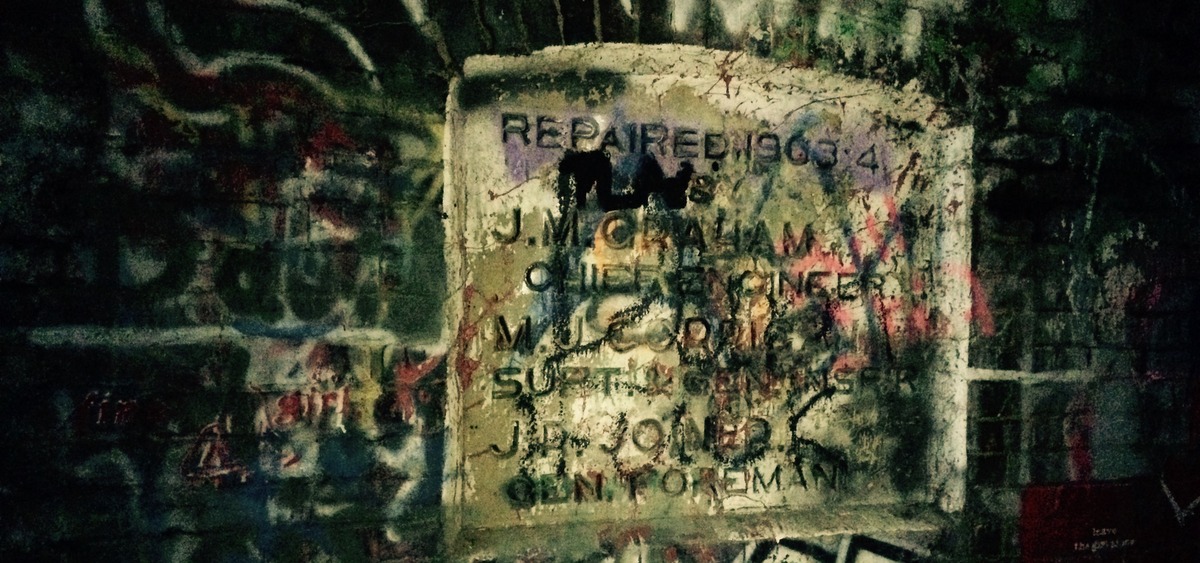

After an hour on the abandon railroad bed and a gravel road, Hutchison pulls the wagon off the road. The riders walk to a heavily wooded area where the town of Moonville once stood.

Hutchison’s words echo off the brick-lined tunnel as he tells his ghost stories, first of a young widow who threw herself off the tunnel into the path of the train; then of a former slave who became a landowner in Zaleski. When freed he learned to read and became a great lover of books. One day, while walking on the tracks he became so engrossed in a book he failed to hear the approaching train and was killed.

But the most often told story Hutchison said, is of the headless brakeman who had a bit too much to drink one night while attempting to uncouple a rail car. The train began to move.

“He desperately tried to clamber out from between them but he slipped and fell and the moving wheel cut his head off,” Hutchinson said.

Hutchison said newspaper accounts tell of a brakeman who died after his arm, not head, was severed. Still the story persists and Hutchison said hundreds of people, some well-respected, tell of seeing a headless man carrying a railroad lantern.

After dark the wagon returns to the Hope School. Hutchison said he learns a lot from his passengers and uses their stories on subsequent trips to the tunnel. He said he likes what he does.

“I do, I like the horses, I like nature, I like people,” he said “It’s kind of an ideal job for me.”