News

Ripple Effect: The Big-Ticket Fix For The Ohio’s Aging Dams

By: Becca Schimmel | Ohio Valley ReSource

Posted on:

A recent breakdown at an Ohio River dam served as a wake-up call about the aging infrastructure that keeps river commerce flowing. The Ohio is one of the country’s busiest working rivers and some navigation controls are approaching the century mark. I went to see these ailing structures and a new multi-billion dollar project in the works.

Critical Stretch of River

Barges are once again moving through this section of the Ohio near Paducah, Kentucky, after a failure at the aging Lock and Dam Number 52 forced a two-day closure in September.

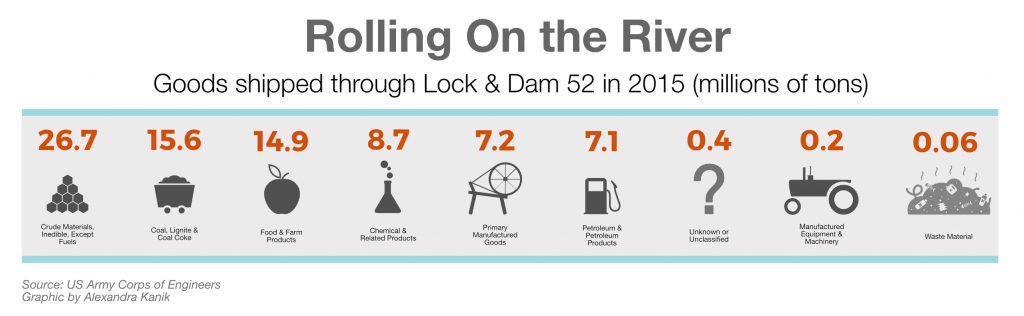

“It’s one of the busiest locations on the inland waterways,” said Army Corp of Engineers Colonel Christopher Beck. “We pass about 90 million tons of cargo through here every year. So it’s critical to both this region, to industry and the nation.”

Lock and Dam 52 uses wooden structures called wickets that work a bit like a bathtub to keep the river at the depth needed for boat traffic. When three wickets broke free of their bases and even more wouldn’t cooperate, a hole let too much water through. That threatened both navigability and a water intake facility used by nearby chemical manufacturing plants.

The shutdown halted traffic and some industry, showing exactly what a failing dam can mean for the region’s commerce. Beck says locks and dams 52 and 53 were originally built in the 1920’s and expected to last 50 years. After 90 years the bandages, tape and temporary fixes are wearing thin.

“They’re very old structures, we replaced about half of them last year but they’re very old,” Beck said.

Beck said it isn’t unusual for dam operators to try to pick a wicket up and be unsuccessful or end up with a small gap. Although the effect of the recent closure was smaller than the Corps had originally anticipated, each breakdown is a reminder of the tremendous ripple effect on the region’s commerce when river traffic is slowed.

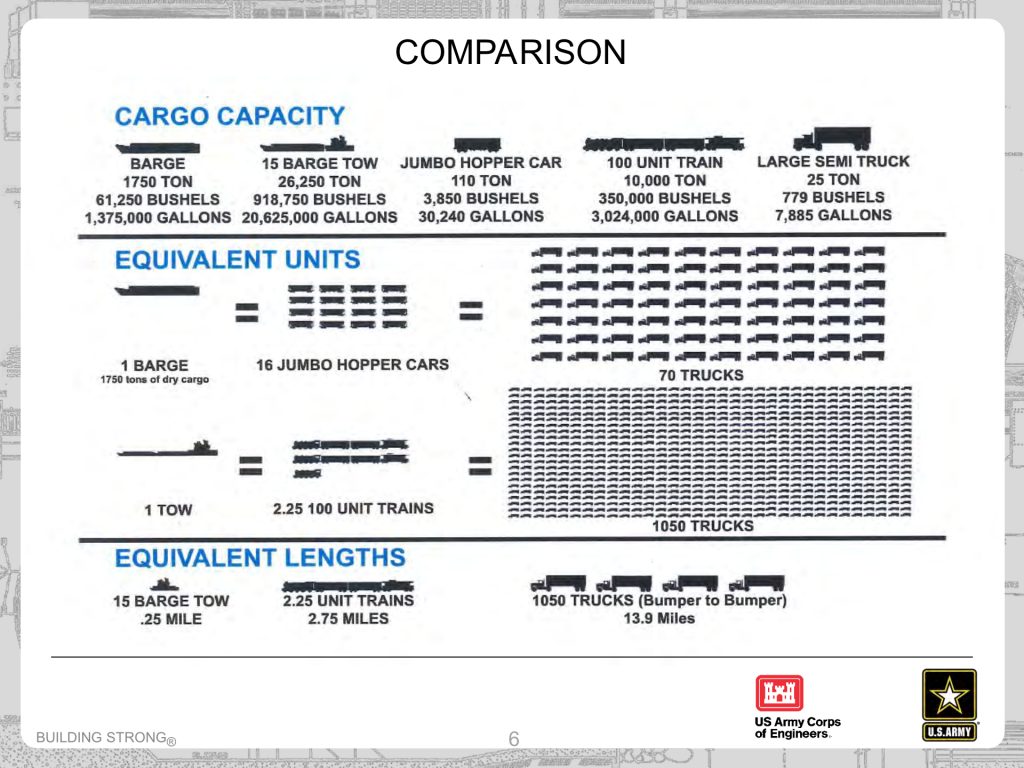

“Industry moves quite a bit up and down the river from coal, to fuels, grains, all those type of things,” Beck said. “Each one of these barges you see going by that’s got a configuration of about 15 different compartments is equal to about a thousand trucks on the road.”

The Big Fix

Just downriver a massive, multi-billion dollar project known as the Olmsted Locks and Dam is underway to keep that commerce afloat.

Olmsted Division Executive Officer Jeremy Nichols led me along a gravel road where pieces of the dam wait to be placed into the river. Stepping onto the dock I climbed into what Nichols described as the Cadillac of crew boats. It’s one of a few pieces of equipment built specifically for the project.

A super gantry crane, which is used to lift and carry the concrete shells down to the river, and a catamaran barge were also built for this project. The Catamaran barge is used to carry those shells into the water where they’ll be lowered and put into place.

Olmsted will be operational in 2018 but it won’t be complete until 2022. During those four years the old Lock and Dams 52 and 53 will be removed. Nichols said it takes a tow boat about three hours to get through the dams. With Olmsted in place that will drop to about one hour.

“The two are more expensive than one because right now they have to maintain those structures with roughly the same amount of personnel each that we have that we would need here,” Nichols said. “So one modern structure has a lot less maintenance compared to two 90 year old structures.”

Alexandra Kanik | Ohio Valley ReSource

Alexandra Kanik | Ohio Valley ReSourceOlmsted’s construction generated about 750 jobs and the facility will employ about 20 when it’s complete. Nichols said Inland Waterways, a federal advisory board that makes recommendations to congress and the army, has made this the flagship lock and dam of the nation.

“As they look at the need for infrastructure upgrades across the United States they’ve identified Olmsted as the number one priority given our location, economic impact and the necessity for replacement of two outdated infrastructure components,” Nichols said.

It will have taken almost 30 years to finish Olmsted from the time the project was awarded to its completion. Nichols said the structure’s lifespan is 50 years but with proper maintenance he thinks it can last about a century.

“It comes back to the old saying, an ounce of prevention is worth a pound of a cure, and that’s true. Eventually everything does run out though, you can only maintain it so long,” Nichols said.

He said the key to Olmsted is doing small maintenance that will add up over time.

Big Cost And Big Benefits

The cost of the project is estimated at a little under $3 billion by completion. With a projected annual net benefit of $640 million dollars, Nichols said the project should pay for itself in about five years.

Corps of Engineers Economist Alex Ryan said the focus is on moving river traffic through the busy area.

“The primary benefit we anticipate for Olmsted will be increasing the efficiency of existing traffic or traffic that’s going to grow in the future,” Ryan said.

Commodities that go through the area are proportionately equal to the passenger traffic at Dallas Love Field, Atlanta Hartsfield, Chicago O’Hare and Los Angeles International airports put together.

“The national level impact of Olmsted is in the reduction in transportation cost so all commodities that are moved on the river are able to be moved more cheaply than they would be over truck or rail,” Ryan said. “That reduces the end user costs for all of those goods.”

“Hoover Dam didn’t take this long”

For the nearby Ashland Manufacturing plant in Calvert City, Kentucky, the new project can’t come soon enough. Ashland depends on the river for materials and water to make a number of pharmaceutical ingredients, and felt the effect of the September closure. Environmental manager Tim Whitaker says the company had to shut down all but two key processes in anticipation of a loss of water.

“It takes awhile to ramp these things back up,” Whitaker said. “This plant runs 24/7 and there was definitely at least a day and a half of lost production for us because of this.”

The closure was a reminder that not just river traffic is affected by dam failures. The effects extend to industry along the river and beyond.

“We’re the sole source on some products, so there could be ripple effects through the economy from shutting down not just this plant but the other plants in Calvert City,” Whitaker said.

He wonders why it’s taking so long to complete Olmsted and argues that The Hoover Dam didn’t take this long. That’s true — remarkably, the Hoover Dam was built in just five years — but it’s also not an “apples-to-apples” comparison. For one thing, the Colorado River does not carry commercial traffic, as the Ohio does.

Some dam construction involves a temporary structure known as a cofferdam used to seal off a section of the waterway. The cofferdam closes an area off, water is pumped out, and construction is done. Once construction is complete the cofferdams are demolished and removed.

But Nichols of the Corps said that’s not feasible in this case.

“A cofferdam that can withstand the Ohio and the elevation during flood stage, that’s a very big structure we have to put in the river anyway. Plus river traffic would be reduced for it,” Nichols said.

Commodities shipped by waterway have become too important to impede traffic even for building a new dam. So Olmsted is being built without blocking the flow.

“They can’t do anything without divers”

Olmsted calls for a construction method called “in the wet.” The pieces of the dam are built on land and then placed in the water. The method saves money and reduces shipping delays.

Nichols said there’s no way to let the water out to inspect or construct the dam; the only way to get a look at the structure as it’s being built is with sonar or divers. Originally, the project didn’t call for any divers.

“That statement wasn’t very well thought out, that’s all I can say,” Mark Cervantes said.

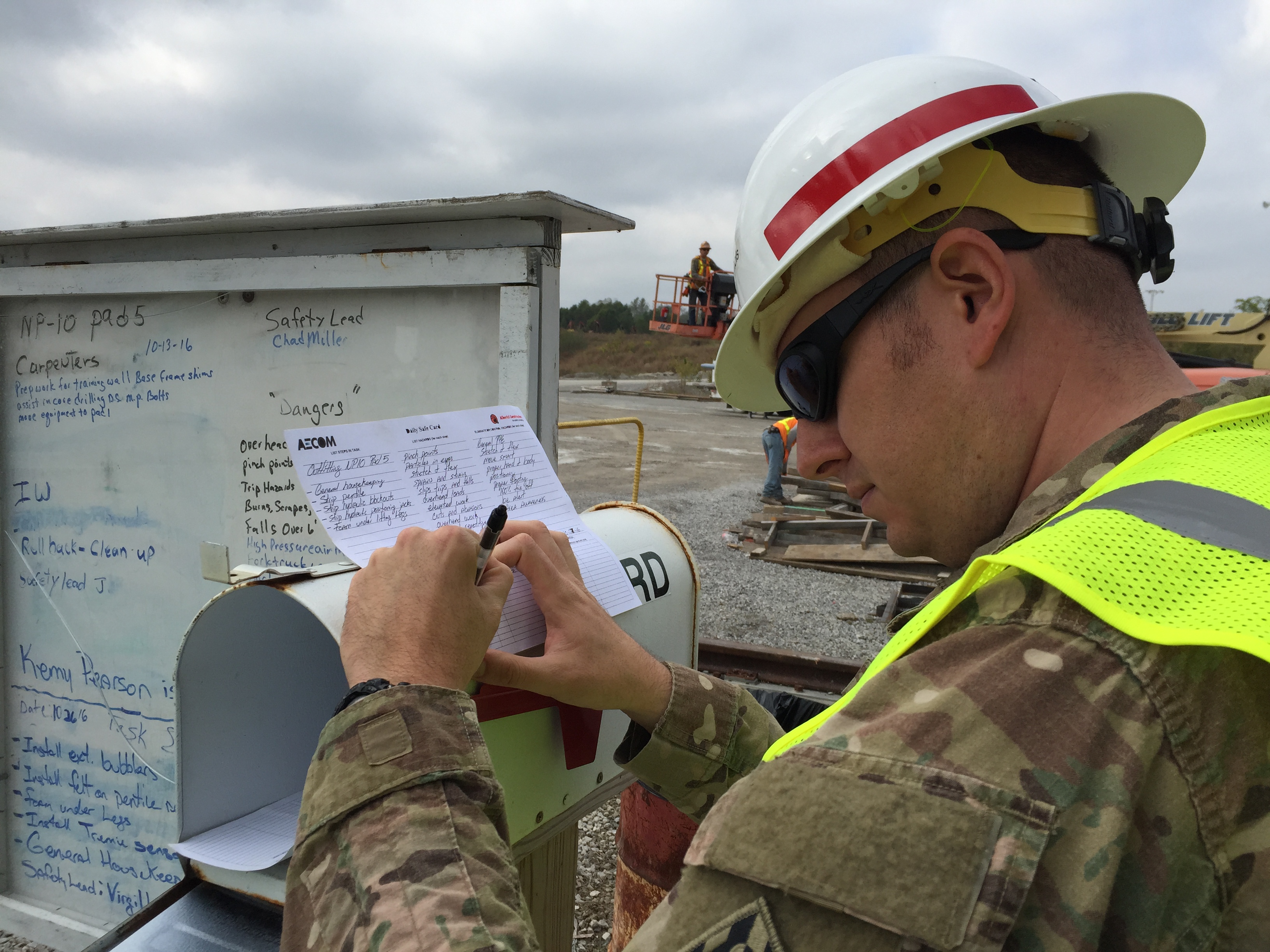

Cervantes, a construction representative, noted that the project recently marked its 10,000 dive.

“They can’t do anything without divers.”

Cervantes said only divers can walk around, feel and tell what it is really like down there and how everything fits. The current is too strong and the water too murky to send remotes down.

He said conditions are always changing. One day divers can go down and see their hands in front of them and the next day they can’t.

Although divers have a support team above them and the occasional Asian carp to keep them company down below, they go down solo. Most of the time they’re cleaning or checking on equipment; every now and then they find a unique Ohio River souvenir: a bowling ball.

“Supposedly there’s somebody upriver that has a pneumatic cannon that shoots old bowling balls in the river,” Cervantes said.

“America’s still building”

Olmsted is two years ahead of schedule but whether industry can wait remains to be seen. Lock and Dams 52 and 53 are rated as failing dams. Industry can only hope that the temporary fixes will withstand another two years. Nichols said this project is getting the Corps’ full attention.

“Everybody from congress on down in the industry sector have said that it’s extremely important that we get Olmsted done so we don’t run into another 52 situation only it being worse,” he said. “Every day that we’re not operational the risk increases on those structures.”

The American Society of Civil Engineers gave America a “D” on its latest infrastructure report card in 2013. Although the nation’s infrastructure is suffering, Nichols is proud of a project that’s working to remedy that.

“You hear a lot of things about America doesn’t build like we used to, our infrastructure’s getting bad,” he said. “When you see stuff like this, it’s a good feeling knowing that so many hundred Americans are doing trade jobs and engineering work and building something massive as part of America’s infrastructure inventory. America’s still building and I like that.”