News

After Obamacare: Rural Health Providers Nervous About Affordable Care Act Repeal

By: Mary Meehan | Ohio Valley ReSource

Posted on:

Alexandra Kanik | Ohio Valley ReSource

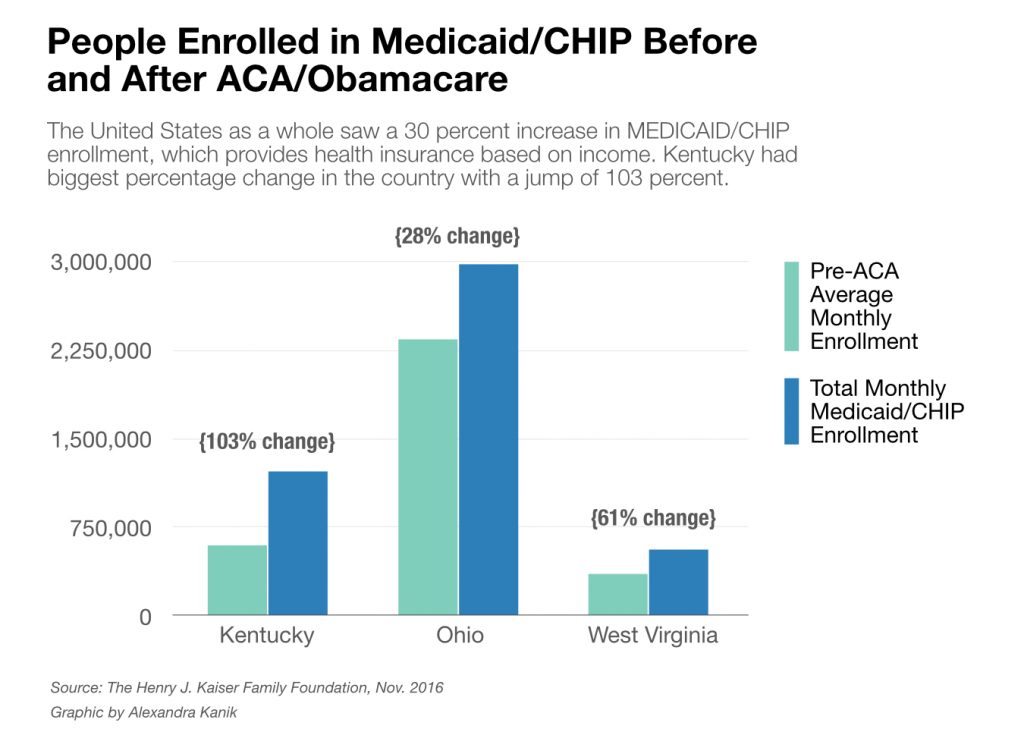

Alexandra Kanik | Ohio Valley ReSourceAs Congress considers repealing the Affordable Care Act, health professionals in Kentucky, Ohio, and West Virginia grapple with what that might mean for a region where many depend on the law for access to care. This occasional series from the ReSource explores what’s ahead for the Ohio Valley after Obamacare. See more stories here >>

Mike Caudill runs Mountain Comprehensive Care Corporation in five eastern Kentucky counties. Many of his 30,000 patients gained insurance through Medicaid expansion under the Affordable Care Act. No one knows if or when those folks might lose coverage. But, Caudill said, the impact could be considerable.

“I don’t want to be a Chicken Little that the sky is falling. On the other hand, neither do I want to stick my head in the sand,” he said. “A lot of it is the unknown. We don’t know what is going to happen.”

Alexandra Kanik | Ohio Valley ReSource

Alexandra Kanik | Ohio Valley ReSourceCaudill runs federally qualified health centers, providing primary and preventive care such as doctor’s visits and vaccinations. They also support community programs including a day care and a service providing fresh fruits and vegetables to 700 people who are chronically ill. If there are significant changes in his revenue because of a repeal of the ACA, Caudill said, those programs that improve the quality of life in the community would be the first to go.

Caudill is not alone. There are hundreds of federally qualified health centers in West Virginia, Kentucky and Ohio. And there are hundreds of rural hospitals providing inpatient and emergency care dependent on government funds to function.

President Donald Trump’s pick of Dr. Tom Price to lead the Department of Health and Human Services is worrisome, said Caudill. In Congress, Price supported big changes in Medicaid and Medicare. Price has also been a consistent foe of the ACA, also known as Obamacare.

“Certainly it gives us some concerns about how it will impact community health centers in general but also us in particular here in Kentucky,” Caudill said.

How To Get Paid

There are hundreds of federally qualified health centers in West Virginia, Kentucky and Ohio. And there are hundreds of rural hospitals providing inpatient and emergency care.

Michael Topchik works for IVantage, a health care research group. He said rural health is a system in jeopardy.

“Right now, I think, we are at a nadir of the ability of that safety net to provide that care in a way that meets local folks’ needs,” he said.

The problem is that both health centers and rural hospitals are dependent on federal dollars to survive. In Kentucky they receive about 70 percent of their revenue from Medicare and Medicaid. Elizabeth Cobb of the Kentucky Hospital Association said financial constraints are forcing rural hospitals to close.

“There has been an increase in the loss of rural hospitals nationwide, and that’s very alarming,” she said.

According to the University of North Carolina’s NC Rural Health Research Program, Kentucky has 16 hospitals at risk for financial distress. West Virginia has two. Ohio, currently, has none. The report does not name the at-risk hospitals and did not expand upon the reasons for the different rates of risk.

Simon Haeder is an Assistant Professor of political science in the John D. Rockefeller IV School of Policy & Politics at West Virginia University. He said Southern states in general have had a greater struggle to provide health care to large, poor sections of their populations. Kentucky, he said, seems to share more characteristics with Southern states. And, he said, in some ways Kentucky hospitals have seen greater benefits from the ACA because so many more rural poor are now insured.

Rural Challenges

There are a lot of common challenges that rural hospitals share and a hospital closure can have a disproportionate effect for rural communities. Transportation is a practical challenge in rural areas, said the Kentucky Hospital Association’s Cobb. A large number of people in rural communities lack access to a car, public transportation is scarce, and additional travel could mean people simply won’t get care. And she said you can also lose something else when you have to leave home — something intangible but no less important.

Alexandra Kanik | Ohio Valley ReSource

Alexandra Kanik | Ohio Valley ReSource“It can separate you from your family and from your support community both physical support and emotional support,” she said.

Plus, she said, people in rural communities are often sicker and older than patients at other hospitals. Many who received health insurance under Obamacare had chronic illness that had gone untreated for a long time.

The hospital has to have the technology to treat those patients. IVantage’s Topchik said as medical technology gets more expensive, a hometown hospital may need to shift to only providing emergency services and outpatient care. That may be the only way to survive.

Changing Times, Changing Health

Caudill agrees times have changed.

“I wish it could be like in the old days of ‘Marcus Welby,’ where a person would walk in and see a doctor and it never would show them paying a bill,” he said.

But Caudill just spent $350,000 for a 3-D mammogram machine. It will also require thousands of dollars a year in maintenance. But it provides the care his people deserve, he said

Topchick said these tough choices that rural hospitals and clinics struggle with are often absent from the national debate.

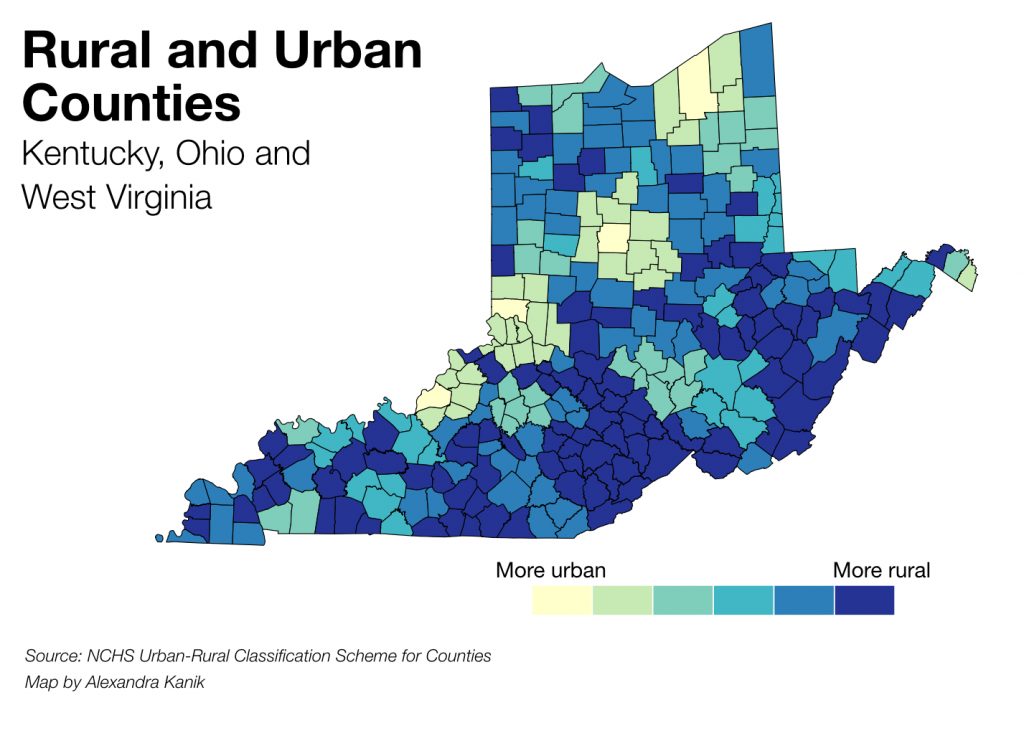

“There really is a tale of two cities,” he said. “There is just not an even distribution. Our country is clearly divided or a rural and urban front.”

The national debate over Obamacare has largely focused on a couple of items: the ACA mandate that everyone have health care; and rising premiums many pay for their insurance. Haeder, the WVU political scientist, said that debate misses some important facts. Private insurance rates and the rates for those who get insurance through their employers have been going up for decades, long before the ACA took effect.

Part of what the ACA has done, Haeder argues, is to highlight the effects some demographic shifts in the country have on insurance systems. Many rural areas now have a higher percentage of people who are sicker and older, as many younger, healthier folks have gone elsewhere for jobs.

“All the problems of rural America are just highlighted in accessing health care,” he said.

Coal Country Concerns

Teresa Fleming is the financial officer for Mountain Comprehensive Care. Despite the campaign rhetoric, she doesn’t think it’s likely that President Trump will bring back mining jobs to eastern Kentucky’s coal country. And she fears coal families in her community will suffer further under an ACA repeal.

“The Affordable Care Act came at the right time and basically correlated with the mine layoffs,” she said. “So that gave our patients safety or at least some security that they would have some kind of coverage so they could go see their providers.”

It is a security under threat in a shifting health care landscape that could also threaten health care jobs, often the biggest source of well-paying jobs still available in rural communities.

The ReSource’s Benny Becker contributed to this report.