News

Considering Compassion: The Science Behind The Ohio Valley’s “Compassionate Cities”

By: Glynis Board | Ohio Valley ReSource

Posted on:

Many towns and cities across the Ohio Valley try to improve their business environment with tax breaks, site development, and other incentives. But how about investing in compassion? A growing body of science points to compassion as an economic driver and more businesses and cities around the region are willing to give compassion a chance.

Science of Compassion

Brain surgeon James Doty directs the Center for Altruism and Compassion at Stanford University and is one of the world’s leading experts on the science behind compassion.

“Compassion can mean many things to different people but in the context of science it’s defined as the recognition of the suffering of another with a motivational desire to alleviate that suffering,” Doty said.

Doty theorizes that the evolutionary success of the human species is tied to our capacity for compassion. He and others have proved there are health benefits to being nice — both for the person being nice, and whomever is experiencing kindness.

“What we have found is that when threat is decreased and when you’re feeling as if others love you or care for you, then your physiology works at its best.”

A side effect of well-tuned physiology: you’re healthier. Turns out you focus more easily and the immune system works better. That means fewer sick days, more focused students, and happier, more productive members of society.

Compassionate Cities

Someone who has really bought into this idea is businessman, inventor, and data-geek-turned mayor of Louisville, Greg Fischer. Fischer said he’s taken a business model of compassion and turned it into a governing strategy.

“If people don’t feel like they are interconnected and interdependent and if people are not being invested in their human potential, you’re not going to optimize your company and you’re certainly not going to optimize your city,” Fischer said. “So, for me, a city is a platform for human potential to flourish. And that’s my definition of compassion.”

Fischer declared Louisville a “Compassionate City” in 2011, signing onto an international charter that calls for commitments to compassionate decision making. Government-sponsored volunteerism has expanded significantly since then, and compassion training is being implemented in public schools and in the city’s jail.

But not, notably, within the police department.

Since 2011, violent crime in Louisville has increased. It’s also one of the most segregated cities in the country. There are certainly other measures of compassion where the city is lagging.

So the big question is: exactly how do you measure compassion or its effects? Researchers in Louisville are working on it.

Compassion Indexing

“While we’re working towards becoming a compassionate city,” University of Louisville School of Medicine Professor Joe D’Ambrosio said, “I don’t know that a lot of people on the street would say we’re compassionate.”

D’Ambrosio is a director at the university’s Institute for Sustainable Health and Optimal Aging. He’s been creating a “Compassion Index” by compiling subjective and objective measures of what he’s defined as a compassionate community.

“We’re looking at surveys and we’re looking at objective data that measure health, governance, ecological resilience, educational attainment and compassionate business standards in living.”

D’Ambrosio wants to know if everyone has access to fresh fruits and vegetables, affordable housing, and transportation. Also, if city government is taking care of people. He also wonders what people are doing to create compassionate environments.

D’Ambrosio’s index is expected to be released this summer. He and his team of researchers hope it will highlight areas where more compassion is needed, and they hope the index will be useful in other cities, too. Because the “Compassionate City” idea is growing.

Compassionate Movement

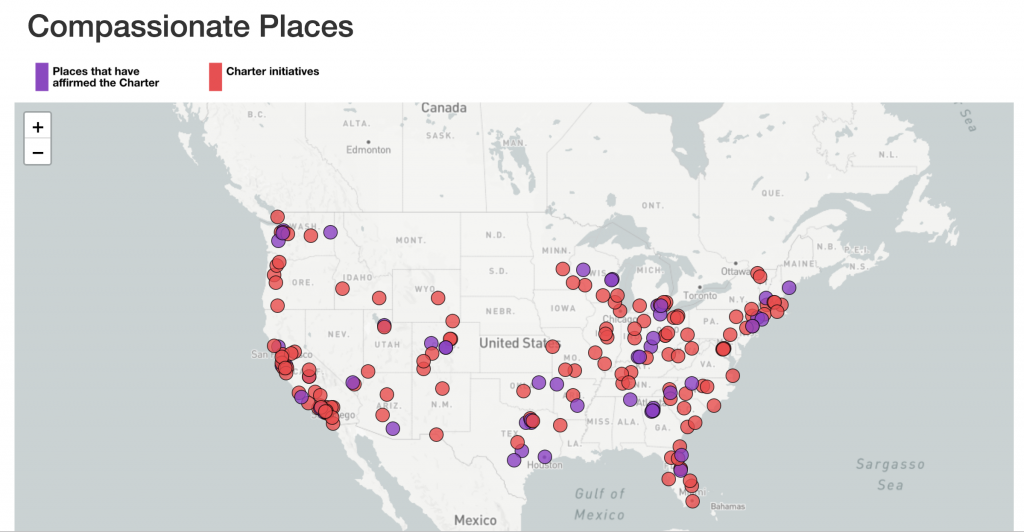

Five cities, dozens of communities, and more than a hundred businesses in the Ohio Valley have signed the Charter for Compassion or begun compassionate initiatives. These include Lyndon, Kentucky, and Cincinnati, Dayton, and Toledo in Ohio. Louisville has hosted 40 other cities and mayors from all over the country who are interested in their model. That includes the mayor of Wheeling, West Virginia, Glen Elliott.

“Anybody can sit on the couch and yell at the TV and be a cynic,” Elliot said. “It’s very, very hard to actually look at some of the tougher issues in your community and decide to do something about them.”

Elliott hopes embracing compassionate policies in government, at schools, and in businesses will help get to the root of major problems the region faces, such as the opioid epidemic.

Some business leaders in the Ohio Valley are taking note of the growing compassion initiatives. Ken Peralta is the director of a non profit called Grow Ohio Valley, which he describes as a “social enterprise.”

“We have a social mission but we operate ourselves as a business,” Peralta explained.

Grow Ohio Valley’s mission is to increase food security and food justice in the valley. It’s started several urban farming initiatives, producing and selling fresh fruits and vegetables. Peralta said the mission requires sustainable business practices, and compassion is key to that endeavor. It’s the organization’s social mission, Peralta said, that attracts A-list talent.

“Even our young Americorps that are coming are top of their class, high grades, biology, engineers,” Peralta said, “and they are working in the fields with shovels in their hands. I think the social mission is what’s attracting them. People, especially millennials, really want to make a difference, and that’s what drives us.”

There’s a growing body of science to support the theory that compassion can improve medical, education, government, and business realms. But measurable impacts of compassionate policy or training on large populations are yet to be clearly demonstrated. That will likely require years to develop and a lot of social and political courage to pursue.

Cities like Louisville, Kentucky, might have a head start.