When people find out their water is impaired, Evans said, there’s often a period of finger pointing and blame. But better information can help communities get to constructive solutions.

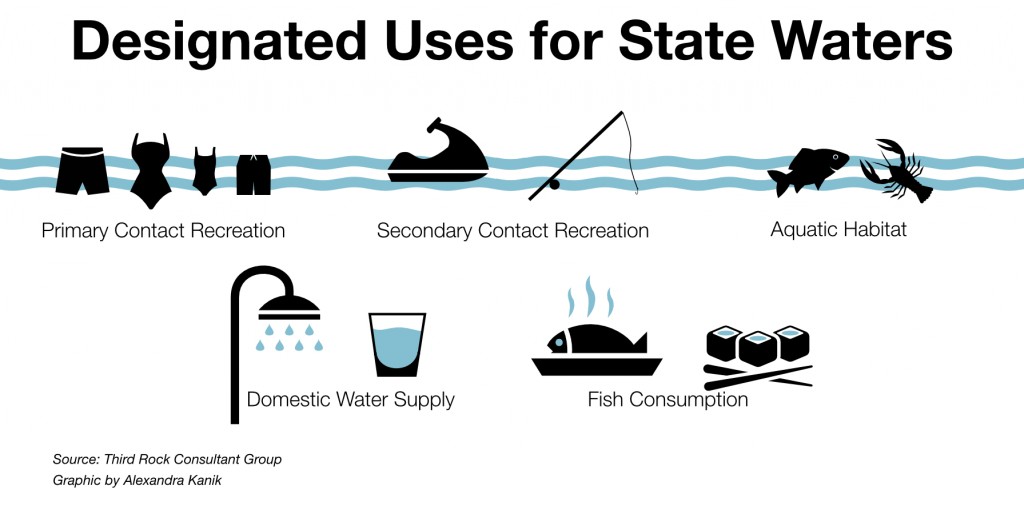

He said he sees people across the Ohio Valley who are concerned about their waterways. “The kids go out and play in the creek and the question is, ‘is the water safe for them?’”

Through data generated with the USGS, the Hopkinsville Water Environment Authority has decided to move forward with two water and sewer infrastructure projects and has secured $39.4 million dollars in funding.

USGS hydrologist Angie Crain said the Little River consortium is breaking new ground in water cleanups, and could be a model for other communities nationwide.

“A lot of people have been looking at this study,” she said. “Being able to use multiple source tracking or tracking nutrients is important. And I think more people, if they can afford it, [will] move that way.”

Cleanup Costs

That could be a big “if” when it come to costs. Crain said the USGS was able to provide a 50/50 cost share for testing the Little River. But proposed budget cuts to both the USGS and the Department of Agriculture threaten funding for water sampling and assistance programs that can reduce polluted runoff.

While most state agencies can perform water tests, Crain said, they don’t often get such requests because the upfront costs and sampling size might not seem feasible or cost effective for state labs.

But just being able to identify the pollution source would give the state “a leg up,” she said.

“Because you’re not shooting broadly, you’re actually aiming into a specific area,” she said. “It makes it effective in terms of water quality but also cost effective so that you’re not blanketing an entire watershed with possible management practices that you may or may not need.”

The Little River group’s Wayne Hunt said that if regulation is a part of the mix, “give me the best data you can,”. “You are talking about regulating somebody’s life,” he said. “So you need to know what you are talking about.”

Data from the Little River project was approved and released in April and a final report is due soon.

“Bring it back home”

David Brame sat on his back porch looking out at Little River. Clean water isn’t controversial in Christian County, he said, everyone wants it. The politics around water, however, can get problematic.

“We are the ones that are going to pay for it and we are the ones that are going to benefit from it,” he said. “We gotta bring it back home. This is our watershed, this is our part of the world, and we need to take care of it.”

A public comment period on repealing the Waters of the U.S. rule is open until August 28th.