News

Strip Mining Science: Trump Administration Stops Mining Health Study

By: Glynis Board | Ohio Valley ReSource

Posted on:

The Perry County Public Library in Hazard, Kentucky, lies along Black Gold Boulevard — a name that nods to the wealth the coal from these hills has generated. On a recent Tuesday evening, however, the library was the venue for a hearing about the full costs of extracting that coal.

A team from the National Academy of Sciences visited to hear what the public had to say about health impacts of surface mining.

Eastern Kentucky resident and artist Jeff Chapman Crane told the Academy committee what life is like near the sites known as mountaintop removal mines.

“The first sounds you hear are the machines, the dozers and loaders, the massive dump trucks,” he said. “You wake your son to get up, coughing from the dust, or the smell of the water, or who knows what. You try not to think about long term consequences.”

For more than a decade Ohio Valley residents have been asking government agencies to respond to the growing body of emerging science that links surface coal mining to health problems in nearby communities. Last year the prestigious National Academy launched a study on the issue.

Many of the residents who spoke at hearings in Hazard and Lexington told the Academy committee they want answers to long-standing health concerns.

“This study is way overdue and it’s really very necessary,” Stephen Sanders said. He directs the Appalachian Citizens’ Law Center in Whitesburg, Kentucky. He urged the committee to look into the effects of dust from mining operations. “It’s very important that we have good scientific inquiry into these subjects.”

Other residents who work in the coal industry spoke against the study and pointed to other, more pressing health concerns.

“I’m very disappointed to have seen taxpayer dollars from the people in this community that deal with real struggles and real health disparities subjected to this cause,” said Kentucky Coal Association President Tyler White.

Virginia Coal and Energy Alliance President Harry Childress agreed.

“We feel our health problems are the results of heredity and are our poor personal habits and choices, not the industry that has provided me and many others with jobs and health care,” he said.

On August 18th, after months of work by the 11 member committee of scientists, the Trump administration ordered a stop to the Academy’s work, citing a budget review at the Department of the Interior.

The move alarmed citizens groups in coal country and many scientists who now wonder what will become of the research and whether they will get answers to the many questions regarding how mining affects public health.

“Thin Excuse”

Public pressure on West Virginia state agencies in 2013 initiated requests to federal agencies to review the growing body of research that led some scientists to call for a moratorium on the practice known as mountaintop removal mining. The Obama administration’s Interior Department and its Office of Surface Mining Reclamation and Enforcement reached out to the National Academy, which started its study last year.

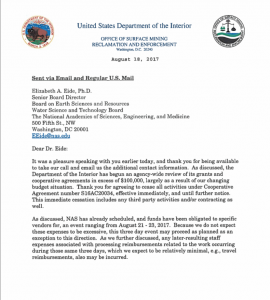

But a letter from the Trump administration’s Interior Department cited an ongoing budget review and asked the Academy to immediately cease all activity on the study.

“The Trump administration is dedicated to responsibly using taxpayer dollars and that includes the billions of dollars in grants that are doled out every year by the Department of the Interior,” an Interior spokesperson wrote in an email reply to the ReSource.

“In order to ensure the Department is using tax dollars in a way that advances the Department’s mission and fulfills the roles mandated by Congress, in April the Department began reviewing grants and cooperative partnerships that exceed $100,000. As such, the $1,000,000 funding agreement was put on hold,” the email continued.

People familiar with the operations of the National Academy say it is extremely rare to have a sponsoring agency stop a study underway.

“I’ve never seen a study halted in the middle,” said Andrew Rosenberg, director of the Center for Science and Democracy at the Union of Concerned Scientists, a Washington-based advocacy group. Rosenberg has participated in numerous National Academy studies during his service in the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. He said he was skeptical about the Interior Department’s stated reason for the stop-work order.

“They have a budget, it’s a continuing resolution from last year, there wasn’t a provision that says, ‘oh we’re cutting your granting program,’” he said. “The money was well known, this is a two-year study in its second year. So, you know, that’s a very thin excuse.”

Healthy Debate

There’s little debate that health outcomes for the Appalachian coalfields rank among the worst in the nation. But communities here remain bitterly divided over reasons for those health problems.

Charles Snavely, secretary of the Kentucky Cabinet for Energy and the Environment and a former coal executive, said in the meeting with National Academy committee that he’s never heard anyone in his community attribute a health problem to coal mining.

“The people of eastern Kentucky who have lived there their whole lives have serious health concerns,” he said. “They are related to obesity, lack of exercise, lack of medical care and drug abuse, those are the things we are concerned about.”

Environmental scientists and epidemiologists who have studied the matter explain that it is hard to prove mining practices directly cause disease. University of Maryland Environmental Scientist Margaret Palmer said it is very difficult to demonstrate health impacts of any one environmental exposure because of complicated factors like lifestyle and health status.

“Proving direct causation,” she wrote in an email, “is not an option for obvious ethical reasons.” But she said scientific evidence is now quite strong that living near surface-mined coal sites “puts a person at far greater risk of health problems.”

Important Work

A lot of the research into mining’s health effects started with Michael Hendryx, an environmental health professor now at Indiana University. Hendryx and collaborating researchers published numerous studies that linked mining to a variety of health issues for those living nearby, including increased rates of cancer, lung disease, and birth defects.

“There’s no question in my mind that this is a harmful practice to public health,” he said.

However, a recent review of research by the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences found a need for further study. The authors said there was a “strong potential for bias” in the current body of literature regarding human health effects.

Hendryx refutes the idea that his work reflects a bias.

“I think that’s nonsense,” he said. “My work has never been supported by any special interest group.”

Hendryx said he worries that the order to stop the Academy’s work is politically motivated, given what he called the Trump administration’s “anti-science, pro-coal orientation.”

Michael McCawley is interim chair of the Department of Occupational and Environmental Health Sciences at West Virginia University’s School of Public Health. He has published research that demonstrates the toxic effects of dust exposure in communities near surface mines. He also said more research is needed but that the existing science is solid.

“The studies we’ve published so far I don’t think need the stamp of approval from the National Academies,” McCawley said. “They’re peer-reviewed studies and they’re there for the public to look at and say, ‘This is what we have to be worried about.’”

Duke University ecologist Emily Bernhardt, who has been studying the effects of mountaintop removal on water quality, said she had hoped the Academy’s work would help resolve some of the lingering questions.

“It’s not clear at this point why people living near mountaintop mines are having poorer health outcomes. And that’s one of the reasons this Academy summary was going to be so important,” she said. “What is the most likely route of exposure? Because I think the public health outcomes are pretty clear.”

The Academy study’s committee chair is John Locke, a professor from the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health. He told reporters in Hazard that his committee members are eager to complete the work they started.

“We think it’s a really valuable study and we’re going to wait,” he said. “And whenever they get through with their review and give us the go-ahead we’re going to jump right back in and do this.”

The Interior Department has not indicated when the review will be complete or if the study will resume.

ReSource reporter Mary Meehan and partner station WMMT’s Mimi Pickering contributed material for this story.