News

Coal Fatalities Rise: Miner Deaths Increase Amid Low Coal Employment

By: Becca Schimmel | Ohio Valley ReSource

Posted on:

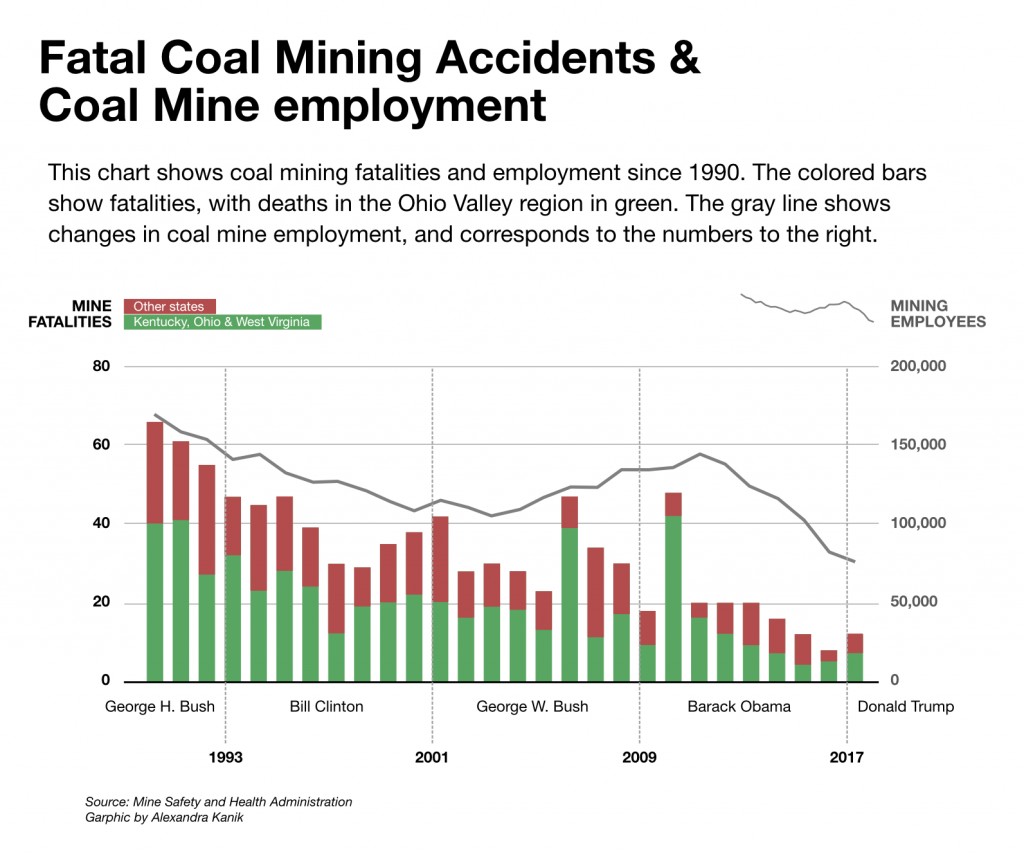

A rash of fatal coal mining accidents in the Ohio Valley region pushed the nation’s total number of mining deaths to a level not seen since 2015, sparking concern among safety advocates.

Already this year 12 miners have died on the job in the U.S., compared to eight fatalities in all of 2016. Two miners were killed in Kentucky and six in West Virginia.

Mine safety experts say this spike in fatal accidents is troubling because it comes at a time when far fewer miners are working compared to recent years, and during a presidential administration pressing to rapidly increase coal production and roll back regulations.

At a rally last month in Huntington, West Virginia, President Trump returned to a favorite theme.

“I love our coal miners and they’re coming back strong,” Trump said.

Mining employment has increased slightly since Trump took office. But veteran mine safety advocate Davitt McAteer said he worries that a coal comeback brings risks for miners. McAteer led the U.S. Mine Safety and Health Administration, or MSHA, during the Clinton administration, and has conducted investigations of mining disasters since then.

“You don’t want to bring them back and send miners to their deaths because you’re not paying attention to safety,” McAteer said. “I’m very much in favor of bringing the miners back. It’s a question of, are they brought back in a way that protects them?”

Last year was the safest in the country’s coal mining history, with eight fatalities. The 12 fatalities so far this year match the total from 2015, a year when there were nearly 25,000 more people employed by coal companies, according to MSHA data.

That has mine safety experts like McAteer concerned. They point to a few factors that could be contributing to a rise in mining deaths: an increase in inexperienced miners, a possible turn away from strict safety enforcement, and a leadership void in the nation’s top mine safety agency.

Safety Vacancy

McAteer noted that for the first seven months of the Trump administration there was no one in the position he once held at MSHA.

“For that position to go vacant says we’re not paying attention to this. And in fact conditions like we’re seeing in West Virginia and across the country, of increased fatalities, come about when we’re not paying attention,” McAteer said.

President Trump appointed Congressional aide and White House advisor Wayne Palmer acting secretary of MSHA on August 22, until a permanent appointment is made. The United Mine Workers of America said in a statement that Palmer has no experience in mining or health and safety.

On September 2, the White House announced the president’s intent to appoint a West Virginia coal company executive to the top MSHA post. David Zatezalo was a top executive at Rhino Resources, which operates mines in West Virginia and Kentucky.The company was the focus of MSHA scrutiny following what regulators called a pattern of violations and a miner’s death at one mine and allegations of interference in mine inspections at another.

Although the agency lacks a leader, it has announced a new approach to safety: what’s called a “compliance assistance” program. An agency data analysis showed that inexperienced miners were more likely to be injured or killed. Seven of the fatalities this year have involved miners who had one year or less experience at the mine where they died.

In response, MSHA said in June it would “encourage mine operators to participate and share information” about new miners on the job.

That raises a red flag for Kentucky lawyer and mine safety advocate Tony Oppegard.

“Every time there is this de-emphasis on enforcement and an emphasis on ‘compliance assistance’ the fatality rate always goes up,” Oppegard said.

Compliance assistance

Oppegard said the main job for MSHA and its inspectors is to enforce the laws and regulations at mines, and the majority of coal mining deaths are caused by violations of safety regulations.

“You know, it’s hard to pinpoint anytime why there are fatalities, but almost every coal mining fatality is preventable. There are very few that you can truly call a fluke,” Oppegard said.

Oppegard said compliance assistance was the approach MSHA tried during the George W. Bush administration, with mixed results. That eight-year period saw some improvements in safety. But the era was also marked by numerous mine disasters, including the Sago disaster in West Virginia and the Darby explosion in Kentucky, which together took 17 lives.

The UMWA also expressed skepticism about the assistance approach.

“The UMWA is not and never has been in favor of so-called ‘compliance assistance’ programs, and this one is no different,” UMWA President Cecil Roberts wrote. Roberts said MSHA is giving mine operators leeway to select who can participate in the program, something he warned will undermine effectiveness of safety training. And he complained that the MSHA change came without notice to the union.

“Despite our 127-year history of dealing with mine safety issues and developing solutions to those issues, MSHA failed to reach out to us at all with respect to developing this program.

An MSHA spokesperson declined an interview request for this story. There are indications that the agency is continuing with some Obama-era initiatives intended to increase enforcement and inspections.

For example, as of July, MSHA was still using a targeted enforcement program established in 2010 in the wake of the mining disaster at the Upper Big Branch Mine in West Virginia. Those “impact inspections” focus on mines that merit increased agency attention and enforcement and included inspections in Kentucky and West Virginia this year.

Celeste Monforton is a former MSHA official and occupational health researcher at George Washington University and Texas State University. She said the balance between strict enforcement and assistance by the agency will vary with different administrations.

“You know one administration, a Democratic administration, is interested in enforcement and wants to do enforcement. And a Republican administration wants to do compliance assistance,” she said. “But in reality my experience has been that administrations do both.”

Monforton said compliance assistance is an important part of what regulators do. However, it should not take the place of the mine inspections required by the law.

“What we want to avoid and what we need to pay attention to is if compliance assistance is supplanting enforcement,” Monforton said.

Monforton added that while any death is one too many, the longer statistical trend still shows improved safety over the years.

State Changes

McAteer said West Virginia Gov. Jim Justice is uniquely positioned to help. The Governor has been involved in the coal mining industry for about 24 years.

“So he is in a specifically opportune position to be able to make that turn-around, whereas others who might not have the background don’t have that kind of industry contact and he’s in a position to make that happen,” McAtteer said.

One of the mine fatalities this year happened in a coal mine owned by Justice’s family. And MSHA has issued citations for safety violations. The Governor did not respond to requests for comment.

Some changes at the state level have drawn criticism from safety advocates. A new law this year disbanded a Kentucky mining board responsible for reviewing training and safety regulations for coal miners.

Kentucky Energy and Environment Cabinet Communications Director John Mura said the mining board was abolished in order to avoid duplication of effort and to save money. He said its duties are still carried out by another body.

Legislators in Kentucky and West Virginia considered, but later turned down, bills that would have reduced the amount of state mine inspections.

Stand down for safety

McAteer said the current increase in fatalities is reason for the mining industry to stop production temporarily in order to re-evaluate safety procedures.

“By having a stand down, where you for hours or for a day stopped production and you say, ‘Let’s take a look at this, because we don’t want to lose any more miners,” McAteer said. “We know how to mine safely and we need to be addressing if there are problems that crop up.”

McAteer said a renewed focus on safety is especially important if the Trump administration aims to fulfill its pledge to ramp up coal production.