News

Opioids On Trial: Can Lawsuits Help Fix The Addiction Crisis?

By: Aaron Payne | Ohio Valley ReSource

Posted on:

When health care and law enforcement officials met recently at a health policy forum in Lexington, Kentucky, to share ideas about the opioid crisis, Kentucky Attorney General Andy Beshear listed some groups that have benefited from money won in a 2015 settlement with Purdue Pharma, the maker of OxyContin.

“We had Freedom House in Louisville and Independence House in Corbin. We had the Chrysalis House in here in Lexington. Hope in the Mountains, that was going to have to shut down, in Prestonsburg,” he said.

Beshear doubled down on a commitment to sue other opioid manufacturers and distributors. He claims they owe the people affected by the addiction crisis.

“I’m not looking for punishment, I’m looking for responsibility,” he said. “And if those companies won’t take responsibility, then I’m going to see them in court.”

Beshear joins a trend of state, county and municipal government officials across the country considering or filing myriad lawsuits in the past year against opioid manufacturers, distributors, pharmacies and doctors they say should take partial responsibility for the addiction crisis.

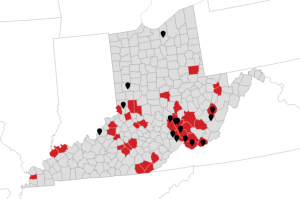

The approximately 60 plaintiffs in the Ohio Valley range from the state of Ohio, population 11.6 million, to the town of Kermit, West Virginia, population 371.

The defendants range from large opioid wholesale distributors such as Cardinal Health Inc., AmerisourceBergen Corp., and McKesson Corp., to small-town pharmacies such as Larry’s Drive-In Pharmacy in Madison, West Virginia.

The officials bringing these suits say the money earned in court would be used to cover what governments have spent to keep up with the damage done by the proliferation of opioid pain pills, and to improve treatment options for those who became addicted. But there are questions about using the courts as a fix for the addiction crisis. Some experts warn that the lawsuits might not succeed and even if they do, they might not bring a remedy in time.

The Strategy

Professor Richard Ausness researches product liability litigation at the University of Kentucky College of Law. He says the plaintiffs face a challenge in proving that the companies created a “public nuisance,” as many of the lawsuits allege.

“Historically, it has been concerned with activities on land,” he said. “A court would have to be willing to expand the traditional boundaries of public nuisance law.”

Another major hurdle will be to prove the companies bear direct responsibility. In similar cases the defense has argued that there are too many steps between selling or distributing a legal substance and the damages of the crisis.

“They clearly have a responsibility to the people they sold the drugs to. But this is a few steps removed from that,” Ausness said.

For example, as part of a lawsuit brought by the city of Huntington, West Virginia, Cardinal Health, a wholesale distributor of opioids, submitted a list of 2,000 organizations the company says could also be liable. This list was controversial because it included Lily’s Place, a treatment center for babies born dependent on drugs.

Ausness said he thinks this argument positions the defense for a chance at success, but it’s not a guarantee.

The plaintiffs, however, may not be looking for a successful ruling to achieve their goals.

“I’m not sure they expect to win or want to win,” Ausness said. “I think what they want to do is settle.”

The cost of litigation is expensive. And the theory is that if drug companies are hit with enough lawsuits, settlement will be a better financial decision than proceeding in court.

Settlements also allow defendants to seal potentially damaging information.

“That’s often the quid pro quo,” Ausness said. “They don’t want stuff getting out that could be used against them.”

A deposition of Purdue Pharma board member and former president Richard Sackler detailing the company’s marketing of OxyContin was put under seal in the Pike County Circuit Court as part of Kentucky’s settlement with the company.

This is believed to be the only time Sackler has spoken on record on the matter, according to STAT, which reports on the biomedical business world. The news organization is battling Purdue in court in an effort to unseal the deposition and other related records.

Following Tobacco Road?

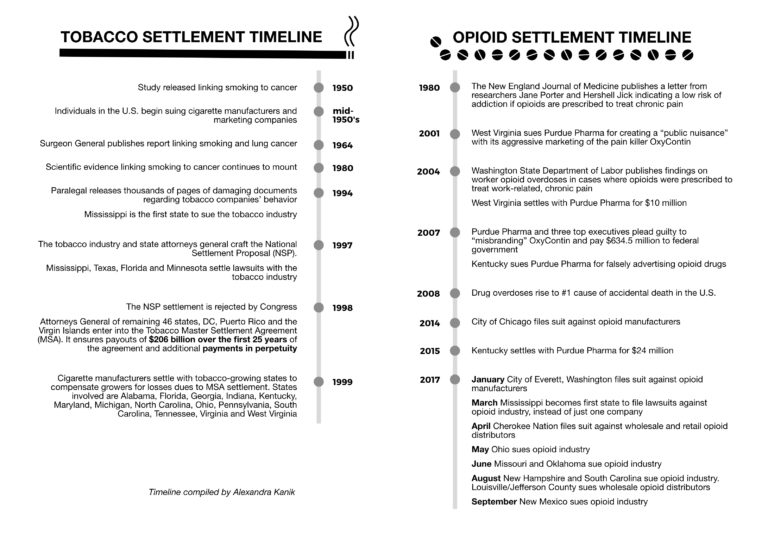

Ausness compares the recent wave of opioid lawsuits to the tobacco industry’s landmark settlement. Industry leaders agreed to pay $206 billion in 1998 after nearly every state sued to recover Medicaid dollars spent on tobacco-related disease.

“The tobacco companies eventually threw in the towel and finally said, ‘We’re getting killed here a little at a time,’” Ausness said.

Part of the Tobacco Master Settlement Agreement prohibited future litigation against the industry.

Ausness said pharmaceutical companies could reach a point where they will opt for that. But he said there are a few key differences with the opioid lawsuits.

Opioids are regulated by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration while tobacco was not. This supports the defense in that they were selling and distributing a legal substance. And Ausenss said there is not yet any “smoking gun” evidence as there was in the tobacco lawsuits.

“They got together and conspired through their trade associations to lie about the risk of addiction and the nicotine content. And they got caught red-handed,” Ausness said.

And if lawsuits succeed, there may not be enough money to go around. There could potentially be thousands of plaintiffs in the opioid litigation as more county and municipal governments file suit.

“I think what we may end up with is something akin to an Oklahoma Land Rush,” Ausness said. “Everybody starts piling on and the ones who manage to get judgments early in the process may end up being compensated while the other ones end up not being compensated if the companies go under.”

A Timely Remedy?

The comparison to the tobacco lawsuits raises another thorny question: Would the money from opioid lawsuits really help those in need?

While smoking rates have dropped since the ’90s, critics of the tobacco settlement say much of the money promised to smoking prevention and education programs went instead into the states’ general budgets.

So far the opioid suits show mixed results in the region.

The Chrysalis House in Lexington is using some of the $24 million settlement from the 2015 agreement with Purdue Pharma to treat the alarming number of babies born drug-dependent.

“[The money is] providing necessary treatment and wrap-around services to the women and children that we serve,” Executive Director Lisa Minton said.

The $350,000 was awarded to Kentucky’s oldest and largest residential recovery program for women out of an $8 million pool through a grant process.

Minton said Chrysalis House will dedicate its share of the funds to hiring additional peer support staff, educational parenting programs and family services to the new mothers who come to one of their three facilities with their babies.

“Funding is always precarious,” Minton said. And grants like these help take some of the pressure off finding enough funding to keep up with the increase in demand for the services.

However, Kentucky’s Office of Drug Control Policy Executive Director Van Ingram cautions that even big money settlements take time to show effects on the ground.

The state’s suit against Purdue, for example, was filed in 2007, a settlement came in 2015, and organizations are just now receiving the money.

“It’ll be a decade before anything results out of these lawsuits, in my opinion,” Ingram said. “So, I don’t think it’s going to have any immediate impact.”

One to Watch

Professor Ausness agrees that these types of cases take time. He points to Chicago’s lawsuit filed against five major opioid manufacturers several years ago.

“It’s still in the pretrial phase after all the back and forth,” he said.

Out of all the similar cases filed across the country, Chicago’s is the furthest along and could have major implications for lawsuits filed in the Ohio Valley.

This means it’s still far too early to tell how the litigation will shake out, and even harder to tell if the results will have an impact in time to keep pace with the opioid crisis.