News

Opioid Emergency: How Trump’s Plan Will — And Won’t — Help The Ohio Valley

By: Aaron Payne | Ohio Valley ReSource

Posted on:

As bad as the opioid epidemic is across the nation, it is even worse here in the Ohio Valley.

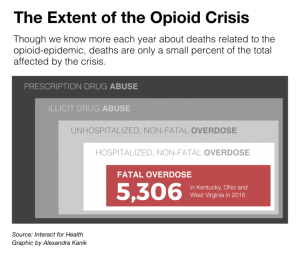

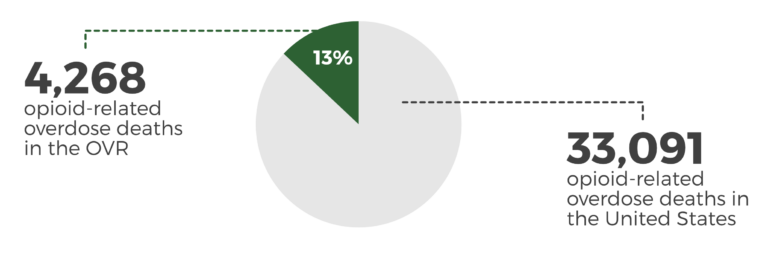

Kentucky, Ohio and West Virginia collectively have a rate of opioid-related deaths that is more than twice the national average.

Last year 5,306 people died from opioid overdoses in the three states — 15 deaths a day. That means that 13 percent of all opioid deaths in the nation occurred in a region with just over 5 percent of the country’s population.

And overdose deaths are just part of the picture. The opioid epidemic reverberates through a community’s hospitals, workplaces, schools, families, even into the arriving generation, as babies are born affected by the drugs in their mothers’ bodies.

So when the president declared this crisis a public health emergency, people in the Ohio Valley were eager to know how that declaration might help with the specific needs of this region, where people struggling with addiction are often in rural, less-affluent communities.

The president’s address included poignant examples from the Ohio Valley’s unfolding tragedy. But thus far the administration’s emergency plan includes frustratingly few specifics or funding options to meet the challenge in the place that is ground zero for the greatest drug crisis the country has ever faced.

Presidential Recognition

The president’s address made clear that his emergency plan was inspired by the Trump family’s experiences in the Ohio Valley.

“In West Virginia, a truly great state, great people, there is a hospital nursery where one in every five babies spends its first days in agony,” the president said. “Because these precious babies were exposed to opioids or other drugs in the womb.”

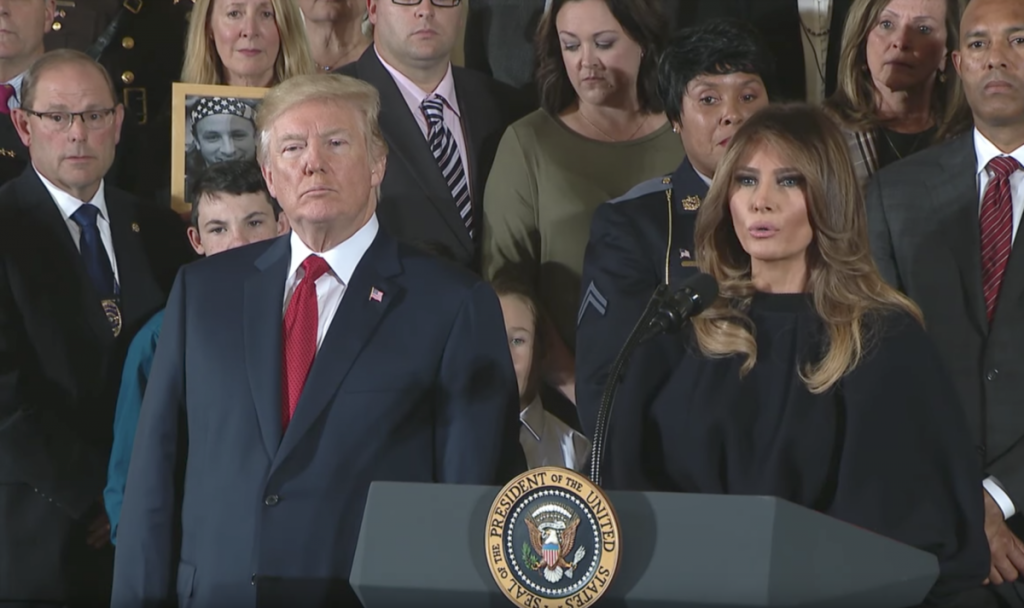

First Lady Melania Trump invited people who deal with addiction across the country — many from the Ohio Valley — to the White House in September to hear their stories.

She followed that meeting up by visiting Huntington, West Virginia, earlier this month to tour Lily’s Place. The clinic treats infants born drug affected and offers resources to both baby and family.

“I learned that to help babies succeed we must help their parents by placing priority on the whole family,” Trump said during her speech Thursday. “Lily’s Place is giving infants the best opportunity.”

West Virginia is one of the hardest hit areas for babies born with what’s known as neonatal abstinence syndrome. Five percent of babies born in West Virginia last year were born drug affected, according to data from the state’s Health Statistics Center.

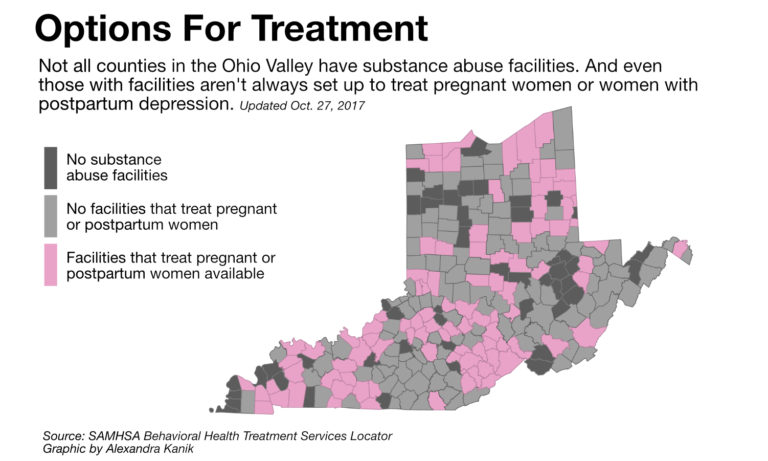

Lily’s Place was the first facility of its kind and draws deserved praise for its pioneering work. However, elsewhere in rural parts of West Virginia there are few options for pregnant women who have substance use disorders. Only 23 percent of the state’s treatment facilities offer services for pregnant women, and the options have been declining.

Earlier this year, West Virginia had 24 substance abuse treatment facilities that were equipped to treat pregnant or postpartum women. Just 10 months later, that number is down to 20 facilities, with some counties losing their substance abuse treatment programs altogether.

Sixteen of the state’s counties have no treatment clinics of any kind.

Similar challenges exist in rural parts of Kentucky and Ohio, where tight budgets and transportation problems make it especially difficult to deliver addiction treatment.

Several key elements of the administration’s public health emergency declaration address rural treatment issues but the plan so far lacks the promised funding. That, coupled with a lack of communication and coordination with regional organizations on the front lines of addiction raise concerns.

Telemedicine’s Promise

The first item listed in the White House proposal released Thursday is aimed at using telemedicine systems to get treatment to rural areas, where waiting lists can be weeks or months long.

Some treatment centers in the Ohio Valley region have been offering telemedicine for some time for other aspects of their services.

Health Recovery Services –with treatment centers across southeast Ohio– uses video conferencing to deliver psychiatric services.

“It was useful,” former director Dr. Joe Gay said. “It did expand capacity.”

Part of Trump’s proposed expansion allows doctors to prescribe addiction treatment medication through telemedicine. Gay said the success of the initiative will depend on how well it is monitored.

“There’s a danger that could lead to more misprescription of the drugs used to treat opioid disorders,” Gay said. “Which can be a problem too.”

Medication assisted treatment is a critical element in a holistic addiction treatment plan. But the medications buprenorphine and methadone, frequently used to wean someone from addiction to heroin or painkillers, are also opioids. And they can further the cycle of addiction if not taken properly.

Offering telemedicine in the most remote areas being affected by the addiction crisis may present a challenge. Data show broadband internet required to host video chat is lacking in parts of the Ohio Valley.

“Most treatment programs would have the technical capacity to do it,” Dr. Gay said. “It could be some problem. But it could be an improvement, too.”

Maximizing Medicaid

Advocates say another proposal in President Trump’s plan could open up more treatment beds by rolling back some regulatory restrictions.

“We will announce a new policy to overcome a restrictive 1970s-era rule that prevents states from providing care at certain treatment facilities with more than 16 beds for those suffering from drug addiction,” Trump said.

What’s known as the Institutions of Mental Disease exclusion was established as behavioral health treatment was trying to move away from large institutions that “stuffed” patients in and neglected them.

Unfortunately, that well-intended exclusion now prevents federal Medicaid dollars from being spent on addiction treatment and recovery services in facilities with more than 16 beds. This creates a situation where there are waiting lists for services and available space at the same time.

Jeff Myers, CEO of Medicaid Health Plans of America, said the exclusion also led to a fragmentation in behavioral health, addiction, and physical health services needed to treat a person struggling with a substance use disorder.

“States are now realizing that that fragmentation leads to poor health outcomes and more costs,” he said. “And they’re moving all those things back together.”

The Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services in 2015 offered states flexibility from the exclusion if they created adequate service delivery systems.

West Virginia was one of the states that applied for the opportunity and received an acceptance letter from CMS earlier this month. Kentucky’s request is still pending. Ohio has no active or pending request.

President Trump vowed to issue waivers in a more timely fashion during his speech but it has not yet been included in any documentation from the administration. Repealing the exclusion altogether would be up to Congress. And legislation has been proposed that would lift the cap from 16-bed facilities to 40 beds.

Advocates say lifting the exclusion could open up residential treatment services that may have been limited before.

“One of the biggest things you have to do is get individuals [with addiction] out of their social milieu,” Myers said. “To get them separated and really looking at how to address their addiction.”

Workplace Effects

The public health emergency plan also includes measures to address the effects the opioid crisis has had on the Ohio Valley’s labor force.

The Department of Labor will issue dislocated worker grants to help people who have been unable to reenter the workforce after reaching recovery.

Addiction treatment specialists say employment is an important aspect of long-term recovery because it provides people the means to deal with other difficulties.

“If the work problem can be solved, often the housing problem can be solved,” Dr. Gay said. “The people who seem to do the best are the ones that get back into the workforce.”

Some companies in the Ohio Valley have already embraced these workers in recovery as part of their drug-free workplace policies.

The Ziegenfelder frozen treat factory in Wheeling, West Virginia, found their role in combating the epidemic by offering people in recovery an opportunity.

“Businesses really need to step to the plate and participate in changing our environment,” President and CEO Lisa Allen said. “We don’t necessarily go out and search for a certain person re-entering. We search for great people.”

The catch for Trump’s proposal is it states the grant availability is “subject to available funding.”

Money Matters

The Trump administration promoted the $1 billion already dedicated to the opioid epidemic, largely through the 21st Century Cures Act and the Comprehensive Addiction and Recovery Act. However the emergency plan does not directly dedicate any new funding sources to meet what experts say is a multi-billion-dollar problem.

The fund for Public Health Emergencies is limited, as it was recently reported to have a total of approximately $57,000.

White House officials told reporters that they would be urging Congress to appropriate an unspecified amount of money into the fund for use in combating the opioid crisis in an end-of-year spending bill.

There is also the issue of how long the additional funding, if any, will last.

Public health emergencies expire after 90 days. The Health and Human Services Secretary can renew the declaration until the targeted issue is deemed under control.

Advocates say these initiatives will need large and sustained funding if they are going to be successful.

For example, if more states receive the exclusion waivers for Medicaid payments, more facilities will be charging Medicaid for their service. And that will require more funding in Medicaid.

“We would hope there would be additional financial resources to allow the states to use them when appropriate,” Myers said.

Trump and the Republican-led Congress have attempted to roll back Medicaid expansions in their attempts to repeal the Affordable Care Act.

Addiction specialists worry that if Trump’s campaign promise of repealing Obamacare is successful the Medicaid expansion that facilitated more access to treatment will go away.

Data from a Harvard/NYU study indicates that in Kentucky, Ohio, and West Virginia nearly 215,000 additional people were able to seek mental health and addiction treatment after the Medicaid expansion.

Little Coordination

Some advocates are also disappointed in how the emergency declaration was developed.

The idea gained traction when President Trump’s commission on opioids released an interim report in May suggesting a national emergency or public health emergency.

A national emergency declaration is different from a public health emergency in that more funding is available to be distributed faster. It also would have allowed for more regulatory power to immediately implement initiatives to combat the opioid crisis.

Trump told a group of reporters in August that he intended to declare the opioid crisis a national emergency. This was two days after then-secretary of HHS Tom Price said such a move was unnecessary.

Months passed with no action on the matter.

Most of the state health officials and drug control organizations the ReSource spoke to had not heard from the White House seeking input specifically for this declaration.

Thursday was the first time many working in addiction and recovery had heard what the plan was.

Stephanie Raglin directs Women’s Hope Center, which offers recovery services in Lexington, Kentucky. She is cautiously optimistic about the emergency plan. But she will be one of many who wait to see what follow up actions the administration takes.

“Hopefully he will listen to those who are out in the field who are doing the leg work,” she said.

Trump said he will have more action on the issue soon as a presidential commission on the opioid crisis issues its final report, perhaps as soon as the first week of November.