News

Trump’s First Year Leaves Obamacare on Life Support in Ohio Valley

By: Mary Meehan | Ohio Valley ReSource

Posted on:

Remember the American Health Care Act, the Better Care Reconciliation Act, or the Obamacare Repeal and Reconciliation Act? They were among the many Congressional proposals to end the Affordable Care Act, also known as Obamacare.

If 2017 was the year of endless Obamacare debates, 2018 could be the year when we see the effects on people who need health care the most. Some health experts in the Ohio Valley are concerned that the “forgotten” folks in rural America could lose access to basic health care as efforts continue to weaken the Affordable Care Act.

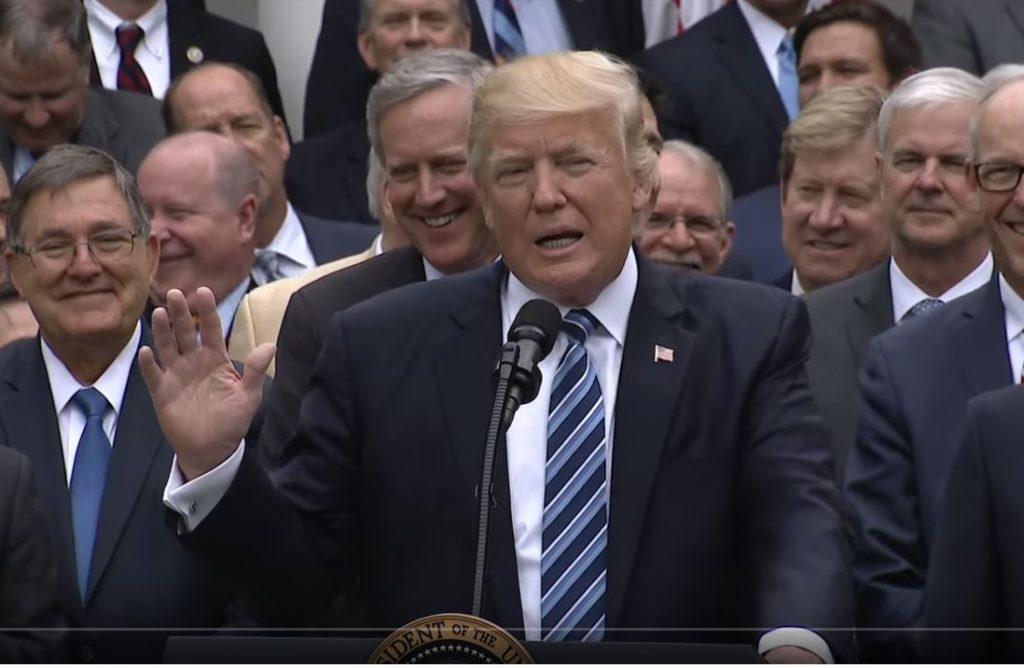

In May, not quite half way through his first year in office, President Donald Trump used the backdrop of the White House Rose Garden to declare Obamacare dead.

“This is, make no mistake, this is a repeal and replace of Obamacare, make no mistake about it,” he said, flanked by cheering lawmakers.

But reports of Obamacare’s demise were premature.

The bill Trump referred to at that White House event was the American Health Care Act. The nonpartisan Congressional Budget Office found 23 million people would become uninsured under the plan, sparking an outcry at town hall events around the country, even in Trump strongholds in Kentucky, Ohio and West Virginia.

And despite many other efforts, the Republican-controlled House and Senate could not pass a bill to fulfill the party’s pledge to end Obamacare.

As the first year of the Trump presidency neared an end, Obamacare remained mostly intact. Mostly.

Mind the Gap

“It has proven remarkably persistent. They kept stabbing at it and failing and failing,” said Simon Haeder, an assistant professor in political science at West Virginia University’s John D. Rockefeller IV School of Policy & Politics, where he focuses on health policy. But Obamacare did change and will likely continue to change in 2018.

One of those changes was included in the Tax Reform Act passed in December. Included in the bill was a provision to eliminate the ACA’s individual mandate, which required every American to have health insurance or pay a penalty. The mandate was a key to stabilizing health insurance markets and funding Obamacare.

Haeder said other upcoming changes will not be high-profile bills tracked through Congress tracked by the hour on cable news. Instead, he said, they are likely to be out-of-the spotlight, wonky tweaks to health policy regulations.

But such tweaks could lead to widely varying use of Medicaid from state to state and determine who has access to care to what kind of care. Because eligibility is based on income, Haeder said, this could have the greatest effects among poor people dependent on Medicaid.

“We are going to have states, where we have states that have low insurance like 4 or 5 percent like Massachusetts and Oregon and places like Texas and Alabama where you have 20, 25 percent uninsured,” he said.

Essentially, he said, Medicaid could become one level of service in one state and something completely different in another. That could already be happening as states file waivers with the federal government to alter some rules for eligibility for Medicaid programs.

Kentucky, one of the unhealthiest states in the nation, applied for such a waiver. The commonwealth becomes the first state requiring some Medicaid recipients to devote 20 hours a week to work, volunteering or school in order to keep their insurance. Health care advocates say that will be difficult in poor, rural areas with few options for transportation. Haeder fears that people will lose coverage because they can’t meet that requirement, shrinking Medicaid rolls.

For Kentucky, Ohio and West Virginia, where there are extremely high levels of cancer, diabetes and other chronic illness, that could mean the already staggering health gaps will grow in states where Medicaid is not embraced.

“The question becomes, when is the discrepancy between two states in the same country too large?” Haeder asked.

Rural Hospitals Concerned

Maggie Elehwany is the vice president of Government Affairs and Health policy for the National Rural Health Association. She said the differences among states are already vast and will get worse as struggling rural hospitals close. Losing them, she said, creates “health deserts” populated disproportionately by the elderly, chronically ill and the poor because people with better options for employment will move away.

That, she said, has real implications as the closest healthcare moves farther away and increasing the travel time beyond what is considered the first critical hour to get treatment for many serious, emergency health conditions.

“There have been so many documented case where patients just haven’t lived because their transport times were too long,” she said.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=jkIGJ8_7gkQ

Elehwany said rural hospitals can also make up 20 percent of the local economy. That means losing a hospital is a multi-faceted blow. The well-paid professionals who work at the hospitals lose their jobs and usually are forced to move out of town. That leads to other businesses, such as grocery stores or banks, closing in the wake of the exodus of medical professionals.She said that property values in an area can even go down, further weakening a crucial source of local tax revenue.

“It really is the nail in the coffin for the economy of a community,” she said.

She said, in the end, denying access to basic, preventative care doesn’t save money. Those patients will put off care until something catastrophic happens and the cost of their care will skyrocket.

Positive Numbers

Dr. Van Breeding works at Mountain Comprehensive Care, a federally qualified health center serving patients in five eastern Kentucky counties. He was also named Country Doctor of the Year in 2017 by Staff Care, a national physician staffing firm that annually recognizes outstanding doctors in small towns.

He echoed Elehwany’s concern while speaking at a recent panel discussion about health care in Whitesburg, Kentucky.

He well knows the how bad health is in the region.

The patients he serves have the “highest levels of blood pressure in the United States, highest levels of opioid abuse, the highest levels of babies born addicted,” he said. “You name it, we have it.”

A study from the Appalachian Regional Commission showed those challenges are spread throughout the region and include some of the highest levels of cancer in the country, with Kentucky at the top of that list, and also shrinking life expectancy.

But Dr. Breeding said he sees access to Medicaid is making a difference every day for his patients. And other potential patients seemed to notice. In 2017, the time frame for signing up under Obamacare was cut in half and funding for outreach efforts was reduced.

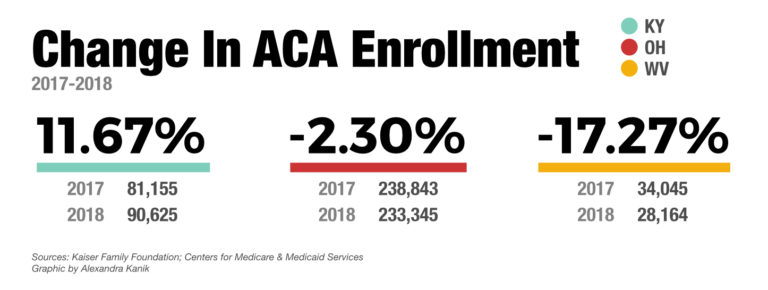

Still, people signed up. Kentucky enrollment rates increase by nearly 12 percent in 2017 compared to the previous year. Enrollment in West Virginia and Ohio dropped in the same period.

Haeder said the never-ending noise over a revolving series of repeal and replace bills may have actually made a broader audience aware that they, perhaps, could be eligible to get health insurance, especially Medicaid.

Breeding also said people who receive health care and those who provide it have seen a measurable difference in the quality of life. That, he said, has the potential to change the future of those long-suffering communities.

“We are getting kids in for the vaccinations that they didn’t have, we are getting them in for flu shots, pneumonia shots, we are saving their lives, we are treating the conditions earlier,” he said. “If people, if politicians, are trying to manipulate the numbers they are lying. We have the numbers we have shown them the numbers.”

He said in his view the disconnect between politicians and patients is clear.

“Politicians are turning their backs on patients in need,” he said. “Our agenda is our patients.”

ReSource reporter Benny Becker contributed to this report.