News

‘America’s Pastor’ Billy Graham Dies At 99

By: Tom Gjelten | NPR

Posted on:

Billy Graham, the most famous minister of his era, died Wednesday at his home in Montreat, N.C., spokesman Todd Shearer tells NPR. In his 99 years, Graham changed the face of evangelical Christianity in America.

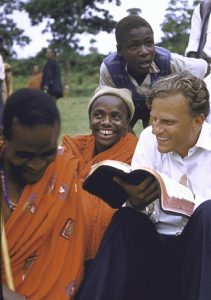

Though he spent his final years in failing health and largely silent at his mountaintop cabin in North Carolina, Graham for more than six decades was in constant motion. He preached to more than 200 million people in 185 countries, counseled presidents and led mass religious rallies that featured professional musicians and huge choirs, in venues ranging from a circus tent in Los Angeles to Yankee Stadium in New York.

His influence as a moral and spiritual leader in 20th century America was such that one historian said Billy Graham could confer “acceptability on wars, shame on racial prejudice, desirability on decency, dishonor on indecency, and prestige on civic events.”

Graham’s fame and popularity, however, derived first from his passionate preaching style, which was partly a product of his upbringing.

He grew up milking cows and pitching hay on his family farm just outside Charlotte, N.C.. His parents were pious Presbyterians who led their children in prayer before every meal and insisted that they learn a new Bible verse each day.

As a boy, Billy did not rebel against that religious discipline, but he was soon attracted to a more raucous form of worship. After attending a few outdoor revival meetings, he decided his Christian calling was to be a Bible-waving preacher like the ones who came through Charlotte in pursuit of lost souls. He subsequently left Presbyterianism to affiliate with the Southern Baptist denomination.

In his determination to replicate the evangelical style, Graham read the sermons of notable preachers and then practiced delivering them himself. According to his biographer, William Martin, Graham regularly closed himself in a tool shed and “preached to oil cans and lawnmowers. Or he paddled a canoe to a lonely spot on the river and called on snakes and alligators and tree stumps to repent of their sins and accept Jesus.”

After graduating from Wheaton College in Illinois, where he met his future wife Ruth, Graham led a Baptist congregation in a Chicago suburb, but he didn’t stay there long. Congregational work was not for him. He wanted to reach a bigger audience, and he had the preaching talent to do so.

His big break came in 1949, when Graham led what he called “a tent campaign” of revival meetings in Los Angeles. Roaming the stage, chopping the air with his hands, and speaking alternately fast and slow, he electrified his audiences.

“The Lord Jesus Christ can be received, your sins forgiven, your burdens lifted, your problems solved, by turning your life over to him,” Graham shouted, before leading the crowd in prayer.

Originally scheduled for three weeks, the Los Angeles meetings were so popular that the organizers extended them to eight weeks. More than 350,000 people are said to have attended the services, in part because of favorable press coverage that came on the orders of newspaper publisher William Randolph Hearst. After hearing Graham preach, Hearst sent a two-word instruction to his editors: “Puff Graham.”

Before long, he was famous around the country. His wife thought he was too loud and too theatrical, but in midcentury America it was a style that worked. As a handsome, blue-eyed young preacher, he projected wholesomeness and charisma. He could command the stage, and his delivery proved perfect for radio and television.

The evangelists who preceded Graham had a mainly regional appeal, whether in the South or the North, but Graham was known as “America’s pastor.” During a 4-month-long “crusade” in New York City, more than 2 million people came to hear him in various venues, including Madison Square Garden. Each service ended with Graham urging people to come forward, stand before him and dedicate their lives to Christ as a 1000-voice choir sang, “Just As I Am, Without One Plea,” the hymn that served as his anthem.

Whereas many previous evangelists had embraced a fiery fundamentalism, Graham was more inclusive. In an unusual twist for a Southern Baptist evangelical preacher, Graham coordinated his Madison Square Garden rally with some big New York churches.

“His determination to cooperate with mainline Protestants and with Roman Catholics alienated his fundamentalist friends,” said Grant Wacker, a Duke Divinity School professor whose book America’s Pastor: Billy Graham and the Shaping of a Nation traces the social and political significance of Graham’s preaching career. “They took great offense that Graham was willing to cooperate with the enemy.”

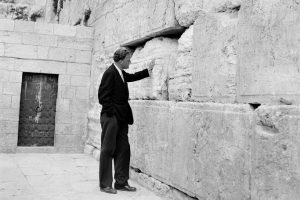

Before long, Graham was one of the most famous and admired men in America. He became a regular White House visitor, meeting with every president from Harry Truman to Barack Obama and becoming a friend and counselor to several. Graham was especially close to Richard Nixon, a golfing buddy, though that friendship was diminished by the Watergate scandal.

Graham initially refused to believe that Nixon was involved, but when the Watergate tapes showed otherwise, he was deeply disappointed.

“He recognized then that he had probably been used, that he had misunderstood something of the president’s character,” said biographer William Martin. “That was a terrible blow to him and caused him to withdraw from the political arena.”

His friendship with Nixon caused Graham additional trouble years later, when a tape of a 1972 conversation revealed that Graham had told Nixon that American Jews had a “stranglehold” on the news media. When the tape was released 30 years later, Graham was horrified and begged forgiveness from U.S. Jewish leaders.

“He did not spin it. He did not try to justify it,” Wacker said. “He said repeatedly he had done wrong, and he was sorry.” Virtually all the Jewish leaders with whom he spoke forgave him, Wacker said.

Over the course of his career, Graham moved steadily toward more moderate positions. Having once tolerated separate black and white seating sections at his rallies, he later insisted that everyone be treated equally, and he invited Martin Luther King Jr. to offer a prayer at one of his Madison Square Garden rallies in 1957. Though not an aggressive campaigner on behalf of civil rights, Graham’s support for racial integration earned him the enmity of the Ku Klux Klan and Southern segregationists.

As a Southern Baptist minister, Graham supported his denomination’s ban on women becoming pastors, but he later said he was prepared to accept their ordination. His daughter Anne Graham Lotz saw firsthand how her father’s views evolved. In a 2011 interview with NPR, Graham Lotz said both her father and her mother were initially opposed when she told them she wanted to teach her own Bible class.

“The traditional role of women in my family had been that the mother stayed at home, reared the children, kept the house, so that the husband – father – could go out and do ministry, which was my mother and father’s case,” she said. “So they just felt that my role was to stay at home and be that traditional type of wife and mother.”

As Billy Graham’s daughter, Anne Graham faced a lot of pressure, but she went ahead with her Bible class anyway, without her parents’ backing. One day, however, they showed up at her class unannounced, and from then on she had their full support. Later, Billy Graham said his daughter was the best preacher in the Graham family.

“I’ll tell you what,” Graham Lotz said in that NPR interview. “I love my daddy. He is so special, and he’s meant so much to me. It’s not a thorn in my side to be known as Billy Graham’s daughter. It’s a privilege.”

After being embarrassed by his endorsement of Richard Nixon, Graham made a deliberate effort to stay clear of divisive issues. Speaking at a crusade in Denver in 1987, Graham said he had been asked by hundreds of news organizations to comment on “certain things that have been happening in the world of religion. I haven’t made a comment yet,” Graham said to thunderous applause.

A big religion story at the time was the rise of the Christian right. The Rev. Jerry Falwell, who founded the Moral Majority organization, was using his leadership position to mobilize conservative Christians in support of President Ronald Reagan and other Republican Party groups, but Graham kept his distance from such efforts.

“I’m trying to stay out of it and just keep preaching the Gospel, because there’s nothing coming out of Washington or any of those places that are going to save the world or transform men and women. It’s Christ,” he said.

Throughout his career, Graham made a determined effort to stay on message. Though conservative in his theology and pious in his personal life, he was reluctant to pass judgment on others.

“He did not think it was his job to criticize other traditions within Christianity, or outside Christianity for that matter,” Wacker said. “He insisted that his sole job was to proclaim the Gospel.”

In this regard, Graham differed not only from the conservative preachers who preceded him, but also from those who followed him, like Falwell or Pat Robertson or even his own son Franklin, all of whom seemed eager to wade into politics.

Billy Graham’s ministry, however, grew to be larger than himself, and it became harder to separate his views from the views of those who spoke on his behalf. The Billy Graham Evangelistic Association (BGEA), which he founded in 1950, produced radio and television programs and published books, magazines and pamphlets. A “My Answer” column that focused on moral and theological questions was actually written by association staff members, even though it appeared under Billy Graham’s name.

By the 1990s, the BGEA was run by Franklin Graham, Billy’s designated successor, and Franklin’s views differed sharply from his father’s. Franklin called Islam “a very evil and wicked religion,” something his more temperate father never would have said. At a rally in 2003, shortly after the United States invaded Iraq, Billy Graham noted that Christianity shared a Middle Eastern homeland with Islam.

“A great deal of the Bible is in Iraq,” he said. “The Garden of Eden was there. Abraham was born there.”

Two years later, when a New York Times reporter asked him whether he shared his son’s judgment on Islam, Graham answered, “Let’s say, I didn’t say it.” Asked whether he, like Franklin, foresaw a clash between Christianity and Islam, Graham said, “I think the big conflict is with hunger and starvation and poverty.” In that same interview, Graham reiterated the position he took in his 1987 rally in Colorado, noting that he did not want to talk about the political issues important to other evangelical conservatives, like abortion or homosexuality.

“I’m just going to preach the Gospel and am not going to get off on all these hot-button issues,” he said. “If I get on these other subjects, it divides the audience on an issue that is not the issue I’m promoting. I’m just promoting the Gospel.”

By the time of that 2005 interview, however, Franklin Graham had a larger public profile than his father had, and he was associating the Graham name with a more humanitarian agenda and with conservative political activism. Through his organization Samaritan’s Purse, he devoted time and resources to charitable work in the United States and abroad. The organization in the coming years would provide aid in more than 100 countries, with an annual budget in excess of $500 million.

In November 2013, on the occasion of his father’s 95th birthday, Franklin Graham organized a huge celebration in Asheville, N.C., with more than 800 guests, largely from conservative Christian and Republican circles. Among those attending the celebration were Sarah Palin, Rupert Murdoch and Donald Trump. Franklin served as emcee for the event. His embrace of conservative Republican leaders culminated in his outspoken support for Donald Trump, whose election as president he attributed to “divine providence.”

Controversy over the Billy Graham legacy was stirred anew with the 2015 publication of a book said to be Graham’s “final chapter.” Titled Where I Am: Heaven, Eternity, And Our Life Beyond, the book had Billy Graham’s name on the cover, as the author, but skeptics questioned whether he had actually written it. Despite the title, the book dealt less with heaven than with hell, describing it as “a place of wailing and a furnace of fire; a place of torment, a place of outer darkness, a place where people scream for mercy; … where many will spend eternity.”

During the months when the book was allegedly being written, Billy Graham was in failing health and suffering from severe memory loss due to hydrocephalus and Parkinson’s disease.

“My personal view is that he had next to no involvement in the writing of that book,” said Wacker, citing Graham’s physical condition and also the book’s fundamentalist message. “That book reflected the views of the early Graham,” he said, “the late 40s, the early 50s. It did not reflect the views of the later Graham.”

In the book, hell is said to be “the place of punishment for those who reject Christ,” but in the later years of his ministry, Billy Graham had been unwilling to make such generalizations.

In a 2005 CNN interview with Larry King, Graham distanced himself from fundamentalists who passed judgment on people, telling King he could not say where non-Christians would spend eternity.

“That’s not my calling,” Graham said. “My calling is to preach the love of God and the forgiveness of God. In my earlier ministry, I did the same, but as I got older I guess I became more mellow and more forgiving and more loving.”

The contrary view expressed in Where I Am, however, accorded closely with the views of Franklin Graham, who wrote the foreword to the book and handled all the publicity for it. When asked by NPR about the suspicion he had written the book under his father’s name, Franklin Graham airily dismissed the idea.

“I don’t have time to write my own books, much less my father’s books,” he said. “There’s no way.”

In an interview with Fox News, he said “every word” in the book was his father’s. As for the fact that the view of hell expressed in the book seemed inconsistent with what Billy Graham had said in earlier interviews, Franklin said that as his father aged, “he’s going back more to the kind of convictions that he grew up with.”

There was no way to verify that claim, however, because Billy Graham himself never said a word about the book or its controversial message. In his final years, he appeared to have little control over what was said or done in his name.

By the time of his death, Billy Graham had been out of the public eye for so many years that the younger evangelical generation had grown up without direct exposure to his ministry, and for many he was a relative stranger. Franklin Graham had taken his father’s place.

The son would never match his father’s fame or reputation, however.

“People who didn’t like Billy Graham spent a lot of time trying to find personal violations of his moral and ethical code, and they couldn’t,” said Grant Wacker. “They didn’t exist. He was a man who maintained absolute marital fidelity and moral and financial integrity. He was an evangelist who lived the way he preached.”

As to whether there might be another Billy Graham, Wacker quoted C.S. Lewis: “The one prayer God never answers is, Encore.”

9(MDI4ODU1ODA1MDE0ODA3MTMyMDY2MTJiNQ000))