News

#MosqueMeToo Gives Muslim Women A Voice About Sexual Misconduct At Mecca

By: Malaka Gharib | NPR

Posted on:

Dressed in a hijab and covered from head to toe, she felt something. Someone — a man — had grabbed onto her butt and would not let go.

The Islamic pilgrimage to Mecca, Saudi Arabia, called hajj, was supposed to be the holiest moment of Mona Eltahawy’s life. When she was 15, she journeyed there with her family. The magnificence of the Great Mosque had taken her breath away. But that man turned the trip into a nightmare.

Instead of telling the authorities, the young Eltahawy simply burst into tears.

“Who wants to talk about sexual assault at a holy place? No one would believe it,” she says, recalling the encounter, which took place in 1982.

In early February, Eltahawy, an Egyptian-American activist and journalist and the author of Headscarves and Hymens: Why the Middle East Needs a Sexual Revolution, shared this story on Twitter. It was in response to a viral Facebook post by a Pakistani woman who shared her own experience of being sexually assaulted at hajj. The post inspired an outpouring of similar testimonies from Muslim women around the world.

For unknown reasons, the post was removed from Facebook, but the conversation continued on a tweet posted by Eltahawy. Her tweet was shared more than 2,500 times and elicited hundreds more stories. She then suggested that women start using the hashtag #MosqueMeToo to organize the discussion.

Sexual assault during hajj is not a new phenomenon. “It’s clearly happening and has been happening, but we don’t know how widespread this is,” says Rothna Begum, the women’s rights researcher for the Middle East and North Africa for Human Rights Watch. “Given the taboo nature of sexual harassment, women are probably not reporting this.”

That — and the fear of stoking the Islamophobia that persists in the world today. Many women are worried that speaking out will give the public a reason to “further blame Muslims,” says Daisy Khan, the executive director of the Women’s Islamic Initiative in Spirituality and Equality. “The tendency is to keep it under wraps.”

Eltahawy thinks that #MeToo, the movement to end sexual harassment in the workplace, has helped Muslim women feel comfortable enough to open up about their abuse. “People pay attention to what famous Hollywood actresses do. But #MeToo has to be available to all people — not those who are rich, famous and white.”

That’s why she started #MosqueMeToo, she says. “I wanted it to be a space where women can share our stories from hajj and the Muslim space.”

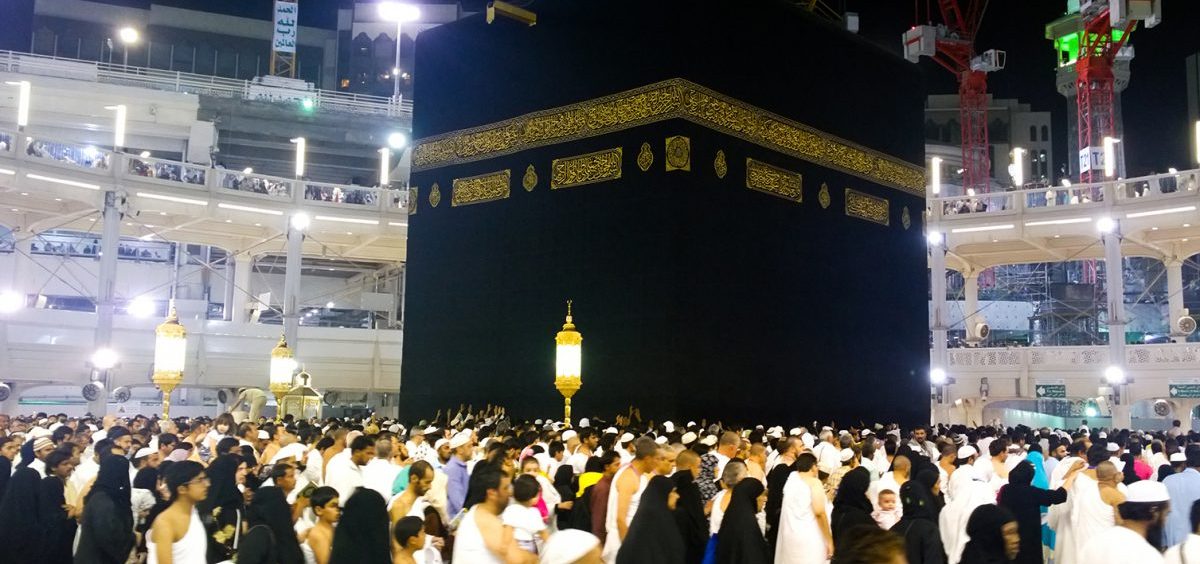

Hajj is one of the five pillars of Islam. It requires Muslims who are healthy and financially able to travel to Mecca at least once in their lifetime. During this time, men and women perform a ritual called tawaf: praying while making seven circles around the Kaaba, a black cubic structure in the middle of the Great Mosque. The Kaaba is believed to have served as a sanctuary for centuries.

It is during the tawaf that many women experience groping, fondling and grabbing, says Eltahawy, according to the responses she’s heard from women. “It’s very crowded. At any given moment, there are thousands of men and women [circling Kaaba at one time].”

The social media testimonies are unprecedented, says Begum. “It’s exposing something that has not been talked about. It’s brave of women to come forward.”

But it’s unclear whether there will be an impact on the authorities in Saudi Arabia, which is in charge of the mosque.

Saudi Arabia, which operates under sharia law, did just put a new law in place to address sexual harassment, says Begum. Created in December 2017, the law states that people who are found guilty of such behavior by the Saudi authorities can be subjected to punishment, which includes flogging or imprisonment. Saudi leadership has called harassment a “contradiction of Islamic principles.”

According to Fatimah Baeshen, a spokesperson at the Royal Embassy of Saudi Arabia in Washington, D.C., the harassment law is part of a broader set of reforms taking place in the country under a program called Vision 2030, which “levels the playing field and facilitates the advancements of women.”

Given the increased access of Saudi women into the public space, “the government is proactively ensuring that along with more mobility women also feel safe,” says Baeshen.

Muslim activists like Khan hope that #MosqueMeToo can trigger change. “I’ve seen things in hajj that I am personally disturbed by,” she says. “Measures need to be taken [to protect women]. There is no place for it.”

Still, a part of her fears that conservative Muslim clerics may twist #MosqueMeToo to women’s detriment. “The danger is that people could use this to try to separate men from women, which could be a disaster. We have enjoyed [praying] in the same space together for [more than 1,400 years],” she says.

In 2006, Saudi authorities attempted to restrict women’s access to the holiest part of the Great Mosque, but it was met with protest from various Islamic groups, including Khan’s.

Islamic leaders like Saba Ghori see #MosqueMeToo as a wakeup call. She’s the board president of Peaceful Families Project, a group that works to prevent gender-based violence in Muslim families.

Ghori says her group is striving to “be part of the solution.” She hopes to “continually raise these issues of [sexual harassment] in the Muslim community” through training and education programs, cultivating support from imams and male allies, and helping the women who do speak out seek justice.

Eltahawy has her own advice. “Saudi authorities should insist that the imam of the Great Mosque give a sermon to all Muslims around the world that it is shameful to harass women and it must stop,” she says.

“And Saudi policemen must be trained in handling complaints, not assaulting Muslim women,” she adds.

She has been assaulted at hajj two times. The second time, she says, was by a Saudi policeman: As she was leaning down to kiss the the outer walls of Kaaba, he fondled her breast.

9(MDI4ODU1ODA1MDE0ODA3MTMyMDY2MTJiNQ000))