News

Exchange of Ideas: How A Rural Kentucky County Overcame Fear To Adopt A Needle Exchange

By: Mary Meehan | Ohio Valley ReSource

Posted on:

Greg Lee, Kentucky’s HIV/AIDS educator, starts the town hall on a somber note.

“How many people in this room know someone who has died of an overdose death?”

It is a standing-room only crowd. Most hands go up.

“Amazing,” he says, sadly.

The meeting is at the Bourbon County Public Health Department, just next to the county’s drug rehab center and down the hill from a playground where used needles are found far too often.

For two-and-half-years there has been fierce opposition and two failed votes over a needle exchange here. On this evening, the key players are gathering one more time for a third debate on the needle exchange proposal.

Mike Williams, judge executive of Bourbon County, has been pushing for a needle exchange since state legislation made it an option in Kentucky. Bourbon County was the first rural county, following Louisville and Lexington, to attempt to start an exchange. After the failed attempts, he hoped 2018 would be different

“I was determined there was going to be a vote,” Williams said.

Cecil Foley, longtime magistrate, represents the most rural parts of the central Kentucky county.

“I was dead against it, to be honest with you,” Foley said of the needle exchange.

Joe Turner is the founder of Recovery Warriors, a group that works for addiction treatment.

“I knew going into the meeting it was going to be an uphill battle,” he said.

In addition to the toll of overdose deaths, the Ohio Valley now also has some of the nation’s highest-risk areas for outbreaks of needle-borne disease such as HIV and Hepatitis C. Health experts say a needle exchange is a strong defense against both overdose and disease. But exchange programs face strong public opposition, particularly in culturally conservative communities.

Which way would Bourbon County go?

“Handouts” or Help?

A skeptical tone dominates the early discussion in Bourbon County’s meeting. One audience member says, “I see those people all over dumpster diving, they’ll just take the needles and sell them to their friends.”

Lee pushes back and says the exchange is provided to prevent that. The woman is unconvinced. “I don’t think it will,” she says.

Others in the audience say addicts are just looking for a handout.

But amid the skepticism there is sympathy as well. When Magistrate Foley uses the word “druggies” some in the audience push back.

“If we are enabling druggies to break the law, that’s illegal,” Foley says.

“These people aren’t druggies, they are human beings,” a man in the audience booms in response, followed by applause.

Foley said later that moment caught him off guard.

“I was surprised, to be honest with you, that they came back so hard,” he said in an interview after the meeting. “I know they are human beings. I’ve a nephew who is in jail. right now for using drugs.”

As the meeting continues, Turner, wearing a ball cap and a black “Recovery Warrior” T-shirt, makes his way to the microphone.

“I’ve been arrested more times than I’d like to admit by some of the very people in this room,” he says, drawing some knowing laughs.

That was before he got clean five years ago, he said. Now Turner’s helping others, including Foley’s nephew. He said he connects up to 10 people a week with treatment. His phone rings constantly as people ask for help.

Turner tells the audience that the people he works with don’t want the life of an addict.

“They want help,” he says. “They will bum a ride, they will take a bike, they will hot foot it to come here and get a clean needle. They beg me for help.”

Health experts laid out how quickly needle-borne diseases can spread and how often people can have full-blown AIDS before ever getting tested. Lee talks about how much it costs to treat cases of HIV and Hep C and how that cost falls to the taxpayers. The price of prevention is far lower.

Difficult Decisions

The difficult discussions over needle exchange programs are happening across the Ohio Valley. Public health officials, increasingly alarmed by disease outbreaks and the unrelenting toll of overdoses, promote needle exchange programs as a way to reduce harm, encourage addiction treatment, and offer disease testing services.

The 2015 HIV outbreak in Scott County, Indiana, which was fueled by needle drug use, is fresh in the minds of many public health practitioners. More recently, outbreaks in southern West Virginia and northern Kentucky have renewed concerns, and the Centers for Disease Control has identified many counties in the region as at high risk for disease.

But the health facts run up against deeply held opinions about the moral aspects of drug use and the notion that a needle exchange enables drug addicts to continue harmful behavior.

Some opposition is rooted in religious convictions. Some is based in fear that an exchange will draw addicts from the surrounding region and bring what was considered an urban problem to a small town.

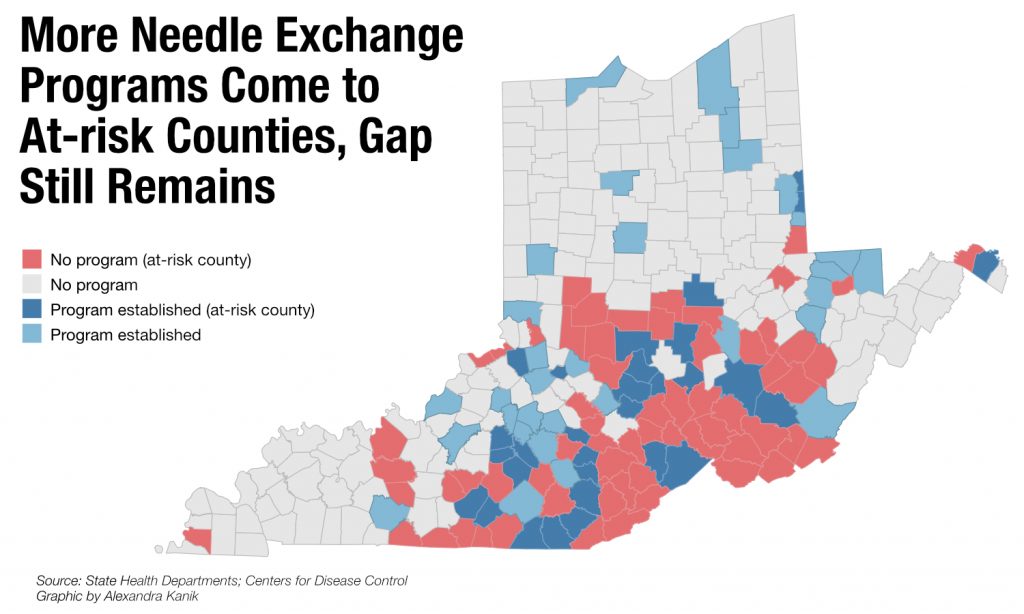

Alexandra Kanik | Ohio Valley ReSource

Even some places that have established needle exchanges are now reconsidering, worried that such programs bring crime into their communities or that local efforts are helping people from other counties or states. Charleston, West Virginia, recently suspended its needle exchange program amid criticism and pressure from the city’s mayor.

But by and large, needle exchange programs have expanded rapidly in the past two years in response to the opioid crisis. At the end of 2016, there were 30 needle exchange programs in Kentucky, Ohio and West Virginia. By the end of 2017, the region established nearly 40 additional exchanges, more than half of which are located in CDC at-risk counties.

Ten more exchanges have already opened their doors in 2018. Ten more exchanges are slated to open in the coming months in Kentucky alone, bringing the total to 46 Kentucky needle exchange locations.

Personal Tragedies

For about an hour the Bourbon County meeting is adversarial, with little common ground apparent. The meeting’s tone starts to shift in hour two as folks like Magistrate Don Menke share personal tragedies.

“My brother-in-law died, overdose. My nephew just died, was missing for a week,” he says. “They found him in a hotel room. Overdose.”

At least five people rise to say they have a relative who is addicted or who has died. Judge Williams says he’s been to the funerals of the children of five friends since he first proposed the needle exchange more than two years ago.

“Those funerals are real,” he says. “That pain is real.”

At this point, Magistrate Foley seems to be having second thoughts about his opposition. But, he says, a needle exchange is still a tough sell for his constituents.

“I’m going to need your help,” he says to the room. “Where I live out in the county, nobody is in favor of a needle exchange. Y’all are going to have to help me tell this story that I heard here tonight.”

The room goes silent as Judge Executive Williams calls for the vote.

All eight magistrates cast their ballots. Foley votes, “Yes.”

There is a pause while the tally is made. The final vote: 6 to 2 in favor.

“The measure passes,” Williams says to thunderous applause.

What Works

In follow-up interviews, Foley, Turner and Williams, still all a little surprised at the outcome, reflected on why the measure was approved.

Foley said that if more people heard the whole story behind an exchange program, they would change their minds like he did.

“It’s more of a safety issue and it’s meant to stop the spread of disease and to save money.”

Turner said it’s crucial that support is homegrown.

“Most people from small, rural towns, they don’t like outsiders,” he said. “It’s got to be grass- roots.”

Williams said he was jubilant at the outcome. But it was hard to tell from reading his face during the meeting. He said he didn’t want to react too much because he knew many people still were strongly opposed. He offered this advice to other community leaders: Persevere.

“It took us three times,” he said. “Don’t give up, and keep presenting the facts.”

The Bourbon County needle exchange program begins operating in May.