News

A New Wave Of Meth Overloads Communities Struggling With Opioids

By: Arezou Rezvani | Rachel Martin | Danny Hajek | NPR

Posted on:

Principal Mary Ann Hale dreads weekends.

By the time Fridays roll around, 74-year-old Hale, a principal at West Elementary School in McArthur, Ohio, is overcome with worry, wondering whether her students will survive the couple of days away from school.

Too many children in this part of Ohio’s Appalachian country live in unstable homes with a parent facing addiction. For years, the community has struggled with opioids. Ohio had the second-highest number of drug overdose deaths per capita in 2016, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

But in McArthur, a close-knit village of about 2,000 in rural Vinton County, there has been a significant shift in recent months.

“They’ve moved on from the oxycodone and OxyContin,” says Hale. “Right now, the biggest problem is meth.”

At the local ER dispatch, paramedics are observing the change firsthand. “We used to do a lot of pills, but now the problem is meth,” says Mike, a paramedic who asked to be identified only by his first name so he could speak freely. “And it’s worse because there’s no Narcan for meth,” he says, referring to the antidote that reverses an opioid overdose.

Though the opioid crisis endures in Ohio, the problem is now compounded by the resurgence of methamphetamine use, an addiction that’s even harder to treat, and can lead to troubling, violent behavior. Local officials and law enforcement are neither staffed nor funded to tackle the growing problem. For McArthur’s residents, the impact has been devastating for families across generations.

Now, meth is back, and not just in Ohio. Communities around the country are raising the alarm.

In 2012, 17,846 pounds of the stimulant drug were seized by law enforcement agents in the U.S. or at the border, according to U.S. Customs and Border Control. By 2017, that number had more than tripled, and much of it now comes from Mexico.

“What everybody is doing now is buying the cheap Mexican meth, and not cooking anymore,” says Vinton County prosecutor Trecia Kimes-Brown.

Meth overdoses have been climbing too, though it’s harder to overdose on meth than on opioids. Overdoses involving psychostimulants, which include meth, increased from 5 percent of total overdoses in 2010 to 11 percent in 2015.

The Drug Enforcement Administration confirms that Mexican drug dealers have taken over the market for meth in the U.S. “Trafficking and usage trends in places like Ohio are on the rise,” says Cheryl Davis, a special agent and a spokesperson for the DEA.

Trying to keep up with the need

There’s only one stoplight in McArthur. A sprinkling of locally-owned shops line main street. The talk of the town in recent months has been the opening of a new grocery store, the first in many years. What they still don’t have, anywhere in the county, is a hospital or an in-patient treatment center.

Vinton County prosecutor Kimes-Brown says that it’s hard to find mental health professionals for users who end up in custody. It’s the criminal justice system, she says, that has absorbed the brunt of the drug crisis.

“I literally have to put them on the street to put this other, more violent offender in jail,” says Kimes-Brown. “That happens at least once a week.”

That has left Vinton County with an enormous bill. In 2017, a sixth of the county’s budget went toward the jail bill — about $578,000, according to county records.

The surge of meth cases has also been overwhelming for local police. It can be riskier for officers to respond to meth-related calls.

“They are more violent,” says Ryan Cain, the lead detective on counternarcotics for the county. He says in a rural county with a culture of hunting, it’s not uncommon to encounter meth users who are hallucinating — and carrying a gun.

Meth can make people agitated and prone to risk-taking, says Andy Chambers, an addiction psychiatrist and researcher at the Indiana University School of Medicine in Indianapolis.

“You can develop dangerous psychotic episodes that can look like schizophrenia,” says Chambers. “The psychosis can get dangerously paranoid — hearing stuff, feeling like they’re being pursued.”

And it can make people neglectful of their lives, their families — anything but the next high. Cain says he’s seen people sell food stamps for 25 or 50 cents on the dollar and steal from family members. “They spend every dollar they got trying to get the next hit,” he says.

Layers of addiction

Counselor Amanda Lee of Health Recovery Services rehab center on McArthur’s Main Street, regularly treats patients struggling with opioid addiction — and using meth. Sometimes, she says, people turn to meth when they’re detoxing from opioids.

“People are going to meth to get off of opiates,” says Lee, whose patients tell her opioids are less available on the street these days, while meth is everywhere. “They go through withdrawal from opiates and sickness and they’re using meth to get through it.”

Lee also says when staff give patients Vivitrol treatments, one of a handful of FDA-approved medications for opioid addiction, it still leaves users craving other highs. Vivitrol is a monthly injection which blocks opioid receptors.

The connection is not so clear-cut for Chambers.

“There’s a lot of urban legend that Vivitrol is causing meth addiction, but it’s not true,” says Chambers. “You’re getting people who were using meth with opiates beforehand and now the meth is prevalent. But it’s not that Vivitrol is causing meth.”

The real problem, Chambers says, is that patients’ meth addiction may be going untreated. While some patients can benefit from Vivitrol or other medication-assisted treatment for opioid use disorder, there’s not a drug that helps with meth.

“The reality is meth has been with us for many years,” Chambers says. In fact, he says, it might be better to stop talking about an “opioid crisis” or a “meth crisis” and admit we have a “polysubstance epidemic.”

What’s underlying it he says, especially in rural areas, is a broken mental health care system.

In fact, 56 out of 88 Ohio counties have mental health care provider shortages, mostly in rural areas. This leaves about 70 percent of the population with unmet mental health care needs in Ohio, and rates are similar throughout much of the Midwest, South and Western U.S., according to data from the department of Health and Human Services.

“I’m concerned about the ongoing shortages,” says Chambers. “If you want decent mental healthcare in the U.S. you better live in the big cities.”

When home is no longer safe

Few have paid a steeper price than the children of Vinton County.

“These kids are living in these environments where they’re not being fed, they’re not being clothed properly, they’re not being sent to school, they’re being mistreated,” says county prosecutor Kimes-Brown. “They have a front row seat to all of this.”

Teachers and staff at West Elementary are often the first to notice that a child is no longer safe at home.

“They’ll just walk into the office and start crying,” says Hale, principal at West Elementary School. “They hug you and you sit down and talk with them and find out what’s going on in their secret little world.”

The staff at West Elementary School is aware of about 60 students directly affected by the drug crisis — about one sixth of their student body.

“I’ve had kids describe to me drug use they’ve seen,” says Rebecca Smallwood, the school counselor. “We had one student who performed CPR on her mom when she overdosed. We’ve had lots of kids see their parents get arrested.”

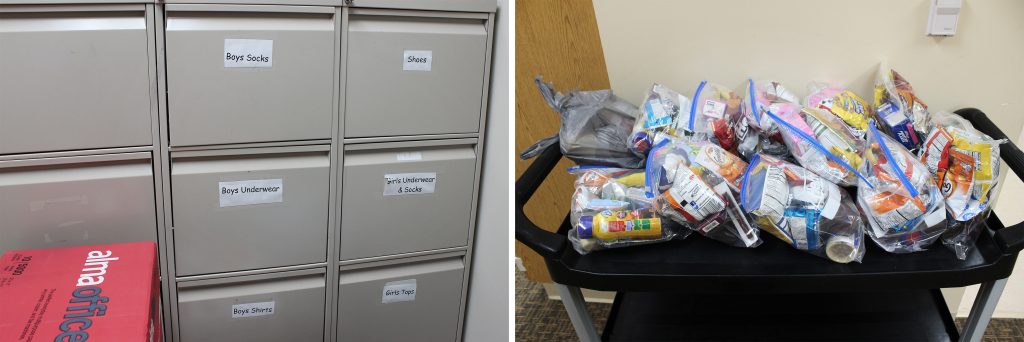

Hale says teachers must know how to read the signs in the classroom. Sometimes the clues are small but revealing. Shoes that are many sizes too small, or students who come to school without socks or underwear. Just outside the principal’s office, staff keep a storage room they refer to as “Little Walmart” stocked with underwear, shoes, T-shirts, and pants for their students.

“[There’s] a slide in their academic behaviors, then aggression, crying, or kids talk about suicide,” says Hale. “We’ve been dealing with one of those [cases] this year. Mom’s an addict, dad went sideways when mom left, and grandma’s raising the little girl.”

This is not uncommon in Vinton County — parents, too consumed with addiction, rely on family members to step in and care for their kids. Usually, it’s the child’s grandparents.

Angela is one of those grandparents.

Her grandson, Billy, was exposed to his mother’s meth addiction early on.

(The grandmother asked NPR to refer to them as Angela and Billy to protect the family’s privacy.)

“One day, she brought him to the house. He was in diapers, he was about a year old and he had a smell to him,” Angela says. “He was beet red, like he’s been out in the sun. She had him in a meth house and the chemicals is what burned his skin, made him red.”

That part of Billy’s story is harrowing enough, but it takes an even darker turn.

While visiting his grandmother, Billy complained about pain. Angela saw signs on his body that suggested her daughter’s boyfriend sexually abused Billy.

“He did things he shouldn’t have to [Billy],” Angela says, through tears. “It did a heck of a number on him.”

Angela and her husband gained full custody of their grandson in April.

It was a difficult transition for Billy. When he started living with his grandparents, Angela says he wouldn’t talk to strangers — he wouldn’t go near men. “Even his grandpa,” Angela says, “he shied away from.”

Angela says he still won’t sleep alone.

“He sleeps on the couch and I’m there because I never know when he’s going to have his nightmares,” she says. “It’s harder on the kids than it is on anyone else.”

Smallwood says that the school is starting to see the effects of kids that have been shuffled from home to relatives or foster care. “That kind of disruption, what it does to a student forever, it’s huge. You just can’t, you can’t use enough adjectives to describe what that does.”

For kids like Billy, school is often the only place they are safe. It is where there is structure and regular meals and people who keep track of their lives from the moment they get off the school bus through the last bell of the day.

But it’s summer time now, a season most kids and teachers look forward to and relish.

At West Elementary it’s different.

“We worry,” says Principal Hale.

9(MDI4ODU1ODA1MDE0ODA3MTMyMDY2MTJiNQ000))