News

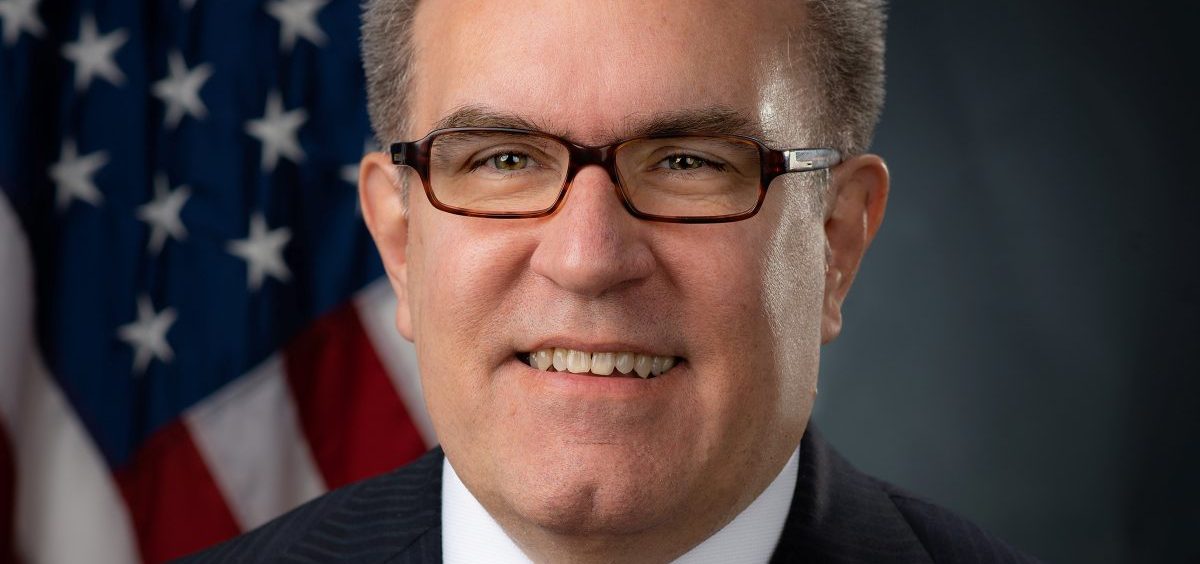

Get To Know Andrew Wheeler, Ex-Coal Lobbyist With Inside Track To Lead EPA

By: Rebecca Hersher | Colin Dwyer | NPR

Posted on:

After months spent staggering beneath the weight of roughly a dozen official ethics probes, mounting bipartisan criticism and one used mattress, Scott Pruitt decided to lay down his mantle as chief of the Environmental Protection Agency on Thursday. But his leadership role didn’t stay vacant long.

In the very same pair of tweets announcing Pruitt’s departure, President Trump named the man who would be taking his place — for now, at least: Andrew Wheeler, the longtime Washington insider confirmed by the Senate as Pruitt’s deputy in April. Come Monday, Wheeler will be the agency’s acting chief.

“I have no doubt that Andy will continue on with our great and lasting EPA agenda,” Trump tweeted Thursday. “We have made tremendous progress and the future of the EPA is very bright!”

In figuring out how that future might take shape, it’s worth a look at the past of the man Trump just entrusted with shaping it. So, who is Andrew Wheeler?

We took a look at his backstory before his confirmation in the spring, when he was still just Trump’s nominee for the deputy job. Here’s a quick review: Wheeler …

- Began his career in environmental law at the EPA, as a special assistant in the agency’s toxics office during President George H.W. Bush’s administration.

- Spent years playing various roles on the Senate Committee on Environment and Public Works, which oversees the EPA, drafting regulations on chemical safety, air and water pollution and climate change — generally seeking to reduce government regulations on industries that generate greenhouse gases.

- Served as longtime aide to Sen. James Inhofe, R-Okla., whom you may recall from the 2015 floor speech in which he rebutted climate change science with a snowball.

- After leaving Congress, worked for years as a lobbyist for some of the largest coal, chemical and uranium companies in the U.S. — including the uranium mining firm that pushed for the reduction of Bears Ears National Monument, which is near one of its processing facilities.

As the CV may suggest, Wheeler is no stranger to the intricacies of environmental policy or the kinds of tasks that await him at the top of the EPA.

“He is not an accidental administrator. He is somebody who has been preparing for a position of responsibility like this really for all of his life,” says Scott Segal, an attorney who has been working on environmental policy for a quarter-century.

“I’ve known Andy a long time,” he adds. “I think he’s a very smart and careful student of environmental law — there’s no two ways about that.”

And Wheeler has presented himself as a consensus builder: “I will turn to the career staff and ask their advice and listen to them,” he told the EPW committee during a confirmation hearing last fall for EPA deputy.

Yet for many critics, who have watched with apprehension as Wheeler ascended the EPA ladder, that kind of experience and approach is beside the point.

“We have in Andrew Wheeler someone who has made a career out of trying to block everything we’ve done to try to protect our children from the growing dangers of climate change — a person who has made a career out of trying to push back against common sense safeguards to protect the air we breathe from dangerous chemicals like mercury, arsenic and others,” says Bob Deans of the Natural Resources Defense Council. “And that’s not in any way a qualification to lead the Environmental Protection Agency.”

Among the foremost concerns voiced by environmental advocates is Wheeler’s position on climate change. His former boss, Inhofe, has made his own thoughts well known, dismissing as a vast “hoax” the overwhelming scientific consensus that greenhouse gas emissions are driving global climate change.

Wheeler, when asked during a confirmation hearing about his own position, proved more circumspect in reply. “I believe that man has an impact on the climate,” he said, “but what’s not completely understood is what the impact is.”

That limber sidestep offers small solace to Deans, who is concerned about what the transition from Pruitt to Wheeler spells for the environment.

“Going from a train wreck to a house on fire doesn’t give us comfort,” Deans says.

Others, such as Sen. Sheldon Whitehouse, offered a slightly rosier outlook Friday. The Rhode Island Democrat, who serves on the EPW committee and has gotten high marks from conservation activists, expressed optimism that Wheeler would prove to be “the honest broker we knew” from his previous work on the committee.

“Clear-eyed leadership at EPA could help prevent the carbon bubble we are headed for as fossil fuel reserves end up stranded and potentially trillions of dollars get wiped off energy company books,” Whitehouse said in a statement emailed to NPR.

One thing both Wheeler’s supporters and skeptics tend to agree upon, however, is that he’s likely a capable candidate to advance the Trump administration’s campaign against environmental regulations. Since Trump took office last year, he has said the U.S. will pull out of the Paris climate accord and has sought to roll back several Obama-era emissions regulations.

Some of those efforts at deregulation have hit snags in the courtroom, because the EPA hasn’t backed up its new position with sufficient data proving its alternatives are more effective and safe.

Which is where Wheeler’s regulatory experience may come in: If the EPA continues with its current agenda, the devil will be in the details.

9(MDI4ODU1ODA1MDE0ODA3MTMyMDY2MTJiNQ000))