News

Can Southeast Ohio Afford Climate Change?

By: Liam Niemeyer

Posted on:

Four girls sit on a black leather couch a few feet in front of Rana Bartee’s heavy-duty camera, surrounded by fake pine trees, artificial snow and holiday decorations in the background. Bartee talks softly, asking the older girls to move a little to the left. Remember to smile, she says. But the youngest girl doesn’t seem to be agreeing.

“I think we might have to tickle the little sis’. Can you tickle her, Chloe?”, Rana asks.

Fingers fly from the sisters, and the youngest girl has more of a smirk now than anything else. Good enough for Rana.

“She definitely has a serious model face,” Rana tells their mom with a laugh.

Rana and her husband, Brandon, work out of their photography studio in historic downtown Pomeroy, Ohio, a village that sits along the Ohio River. They’re some of the younger business owners in town, and their business is expanding; not only do they take yearbook photos for three local school districts, but they’ve had to limit the number of high school senior photo shoots they’re taking each year because of demand.

When they first bought the riverside building, they knew Pomeroy, like many communities along the Ohio River, had a history of flooding. The Bartee’s front door is only a football field away from the water. They were reminded of that history when they were renovating the building’s original tin ceiling.

“Yea — there was flood silt. There was silt in the river above the tin ceiling. It was from whenever it was up in ‘37,” Rana says.

That is the year the Ohio River rose to 60 feet, 12 feet above flood stage. The second floor of buildings on State Route 833, including the building where the Bartees’ business is, was waterlogged. Even the Meigs County courthouse on higher ground took on some water.

The Bartees had never experienced a flood in Pomeroy before, but when the Ohio River in February rose to 50 feet, pushing three feet of water into their business, it wasn’t a complete shock to them. Many residents in Pomeroy consider flooding a way of life in their village.

“The last flood we had was in 2005. I was fifteen years old. We always knew it was a possibility,” Brandon says. “We weren’t shocked when it came in, but it did throw us off balance a bit. Like, ‘oh, the thing that people said could happen is happening now.’”

The Bartees say they were lucky. They were in the middle of renovations, and most of their photo equipment was stored away. They only had to take down a few thousand dollars worth of drywall.

Flooding in February caused an estimated $44 million in public damages to Ohio communities, including damage in river cities from Cincinnati to Marietta and washed away roads in rural townships. Close to $3 million of that was reported in Meigs County, according to local, state and federal emergency management agencies.

A study published in 2017 by the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers (USACE) in collaboration with several universities and federal agencies predicts that spring flooding events, like the one in February, could become more frequent and intensify in a significant way because of climate change.

The study predicts by the end of the century, southeastern Ohio could be almost as hot as Atlanta, Georgia. Because of increased temperatures, one result is more seasonal fluctuation in river levels. Water levels in the spring could be as much as 25 percent higher by 2040 and as much as 35 percent higher by 2099. In the fall, it’ll be the opposite: water levels lower than normal, potentially triggering severe drought.

“Most of the precipitation happens in late February and March. And if that precipitation all comes in right into the river and doesn’t stay on the ground and get stored as snow, then your late winter, early spring flow is going to get bigger,” Dr. Patrick Ray, a University of Cincinnati an environmental engineering professor familiar with the study, says.

Dr. Ray says this study is just a start of climate change data being collected in the region; climate scientists are most confident that temperatures are increasing, which can cause increased flooding and drought. How severe these natural hazards may be remains to be seen.

To fight climate change and the prospect of future flooding, the USACE is also working on a way to help communities like Pomeroy find funds to adapt.

Dr. Kate White leads climate preparedness at the USACE and supervised the Ohio River Basin climate change study. She published another study last year that created a prototype data tool to match a community’s needed climate change projects with the right grants.

“What we’re trying to do with that is to get a way to facilitate communities who don’t have a lot of assets that say ‘well who do I even go see?’” Dr. White says.

But even if the right grant is found, paying for it is another issue. Most public grants usually have local governments contribute a small portion of a project’s cost. For small villages like Pomeroy, even that can be a hurdle.

Financial Challenges & Tough Decisions

All counties in Ohio are required to plan for disasters like flooding through what’s called a Local Hazard Mitigation Plan (LHMP) that addresses the risk local communities have to potential natural disasters and proposes various projects to prevent these disasters.

With each county updating their plans every five years, this process qualifies Meigs County and Pomeroy to apply for various Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) grants to help repair road damages like after February’s flooding and for preventative projects, ranging from adding larger culverts for a stream to adding flood walls for a community.

Some FEMA grants are only made available after a presidential declaration of disaster, like the one declared in April to help counties in Ohio repair flooding damage from February.

Steve Ferryman is the Mitigation Branch Chief at the Ohio Emergency Management Agency and helps communities renew these plans and apply for federal grants.

“The way we kind of view [climate change] here at EMA is that climate change isn’t a hazard in and of itself, but it is an amplifier of existing hazards, be it flooding, severe storms or wind storms. Most [LMHP’s] don’t address it as a stand-alone hazard,” Ferryman says.

Ferryman says most federal grants require counties to contribute a small portion of a project’s cost, called a “match”. But Pomeroy Mayor Don Anderson says getting grants for multimillion-dollar projects, aren’t always possible for rural villages and townships with tight budgets like his own.

“You look at a small village like Pomeroy, Middleport or any other small village along the Ohio River, and you can obtain some funding for a project. But let’s say it’s a million-dollar project, and it’s a 75-25 split. The match is a lot of money for a small village that doesn’t have a lot of money laying around,” Anderson says. “You can even get to the point where you have to turn down grants because you don’t have the matching funds.”

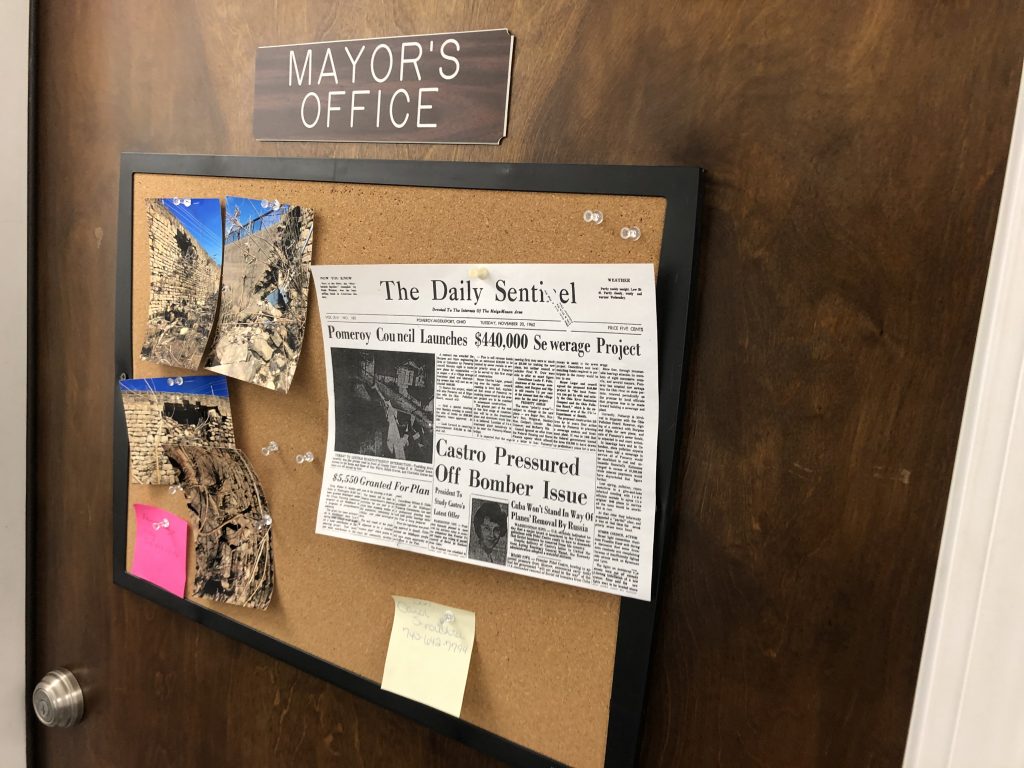

Pomeroy’s largest flooding-related project currently is an effort to repair its downtown parking lot wall. Because of erosion caused by flooding, the foundation of the parking lot is unstable, threatening to close the village’s main throughway, State Route 833.

After years of lobbying U.S. Rep. Bill Johnson and state officials, the village was able to secure funding from USACE for the $1.92 million project. Even then, the village didn’t immediately have the money. Anderson says the village had to borrow about $675,000 to pay for their portion of the match.

The village is also taking out another loan, provided in part by the Ohio Environmental Protection Agency, to pay for updating and extending its combined sewer system. By separating sewage from stormwater, sewage isn’t pulled into the streets when floods do happen.

Ohio Department of Public Safety officials say that one cheap flood-prevention project common to southeastern Ohio is when federal funding is used to buy a flood-prone property, demolish it and turn the area into perpetual green space.

Anderson says considering the historic value of downtown Pomeroy and the economic value businesses there bring to the village, he doesn’t think demolition and relocation of downtown is feasible or wanted.

While the downtown buildings could be made more water-tight, Anderson isn’t sure how to protect the village if climate change means an increased chance of another devastating flood like in 1937. And there isn’t money to continually take out loans for expensive projects that could protect the village, like relocation or flood walls.

“If you’re talking catastrophic issues, short of flood walls, I don’t know what you could do to prevent the kinds of damages from those kinds of floods. Especially with Pomeroy, [flood walls are] going to destroy one of the things that makes the village unique in that you have a nice view of the river,” Anderson says.

Resilience Toward The Future

Despite these financial challenges, Dr. Kate White says the time to act against future flooding is now.

“If it happened before, it’s going to happen again. As you look to the future and see some of these increases in river flow, which could be pretty large, you might have to think about relocation,” Dr. White says. “Because you have plenty of time to think about it now, how would you do in a way that maintains the tax base while meeting all of those other socioeconomic needs?”

She says finding solutions means thinking creatively about how to get funding for disaster mitigation projects, including all potential grants offered at the federal level, state level, and in the private sector.

Dr. White mentions another study to be published next year that identifies four key factors needed for a community to adapt to climate change: someone to lead changes, goals for said change, backing from the local government for change and help from outside funding.

She points to how the city of Greensburg, Kansas, relocated their high school and hospital after a catastrophic tornado as evidence that a community can be resilient if the support is there.

For Brandon and Rana Bartee, they say the future of their business makes them anxious; the chance of a 100-year flood is always a possibility.

But they believe Pomeroy can persevere because what they saw the night of the flooding in February: community cooperation and kindness, working together to clean up their village.

“We were eating, drinking and having a great time. We waited until it started going back down around 1 a.m., and we all got to work together. The first building that cleared out, we all helped on that and so on,” Brandon says. “I mean, I’m going to remember that night for the rest of my life. I hope I don’t have too many nights like that, but it really is beautiful the community we have here.”